In 2019, the international collaboration known as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) made history by producing the first-ever image of a black hole. The object in question was the supermassive black hole (SMBH) residing at the center of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy, located about 55 million light-years away. The SMBH, designated M87*, is also noted for the powerful streams of charged particles emanating from its poles that travel close to the speed of light. This "relativistic jet," as they are known, is powered by the SMBH's powerful gravity and rapid rotation.

Using the technique known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), where light is combined from multiple observations (or observatories) to create a detailed picture, astronomers were able to put accurate constraints on the size and mass of this gravitational behemoth - 25,000 AU (3.7 trillion km; 2.3 trillion mi) in diameter and with a mass of over 6.5 billion Suns. However, astronomers were still unsure exactly where the jet originated around the black hole. Using data collected by the EHT on this jet, based on observations made in 2021, an international team of researchers has uncovered clues about the jet's origin.

The study was led by Saurabh, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR), Hendrik Müller of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), and Sebastiano von Fellenberg, formerly a member of the MPIfR and currently a researcher at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (CITA). They were joined by the EHT Collaboration, consisting of 300 members from 60 scientific institutions worldwide. Their research was detailed in a paper published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics

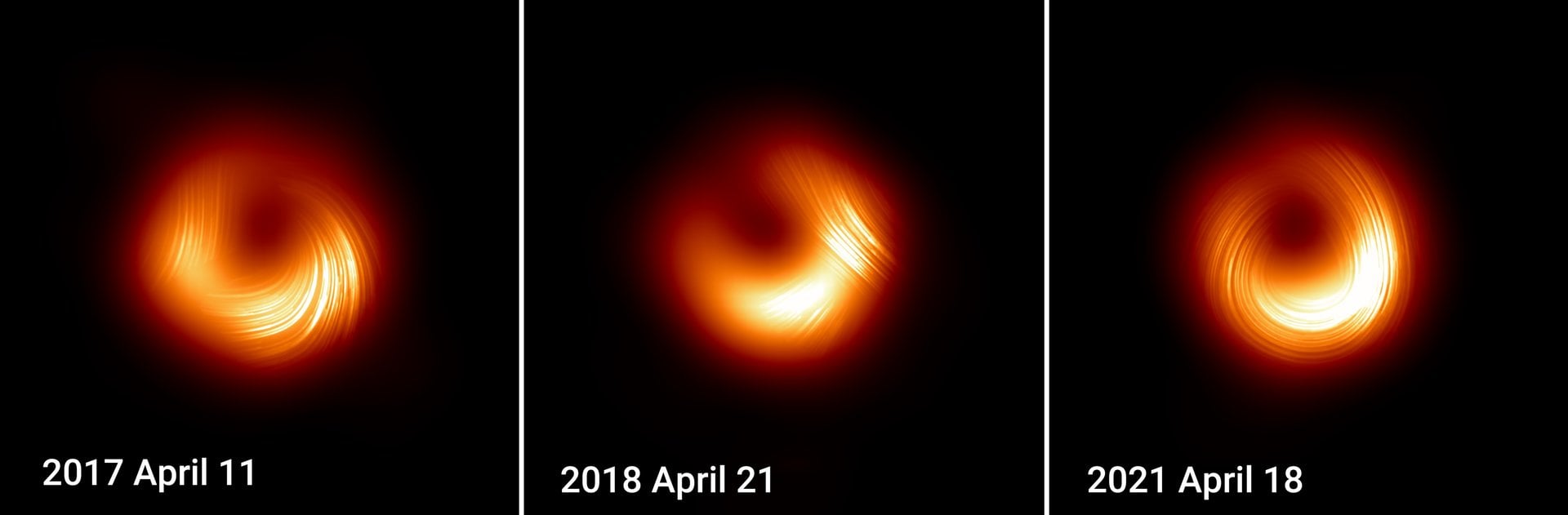

New images from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration show a dynamic environment with changing polarization patterns. Credit: EHT Collaboration.

New images from the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration show a dynamic environment with changing polarization patterns. Credit: EHT Collaboration.

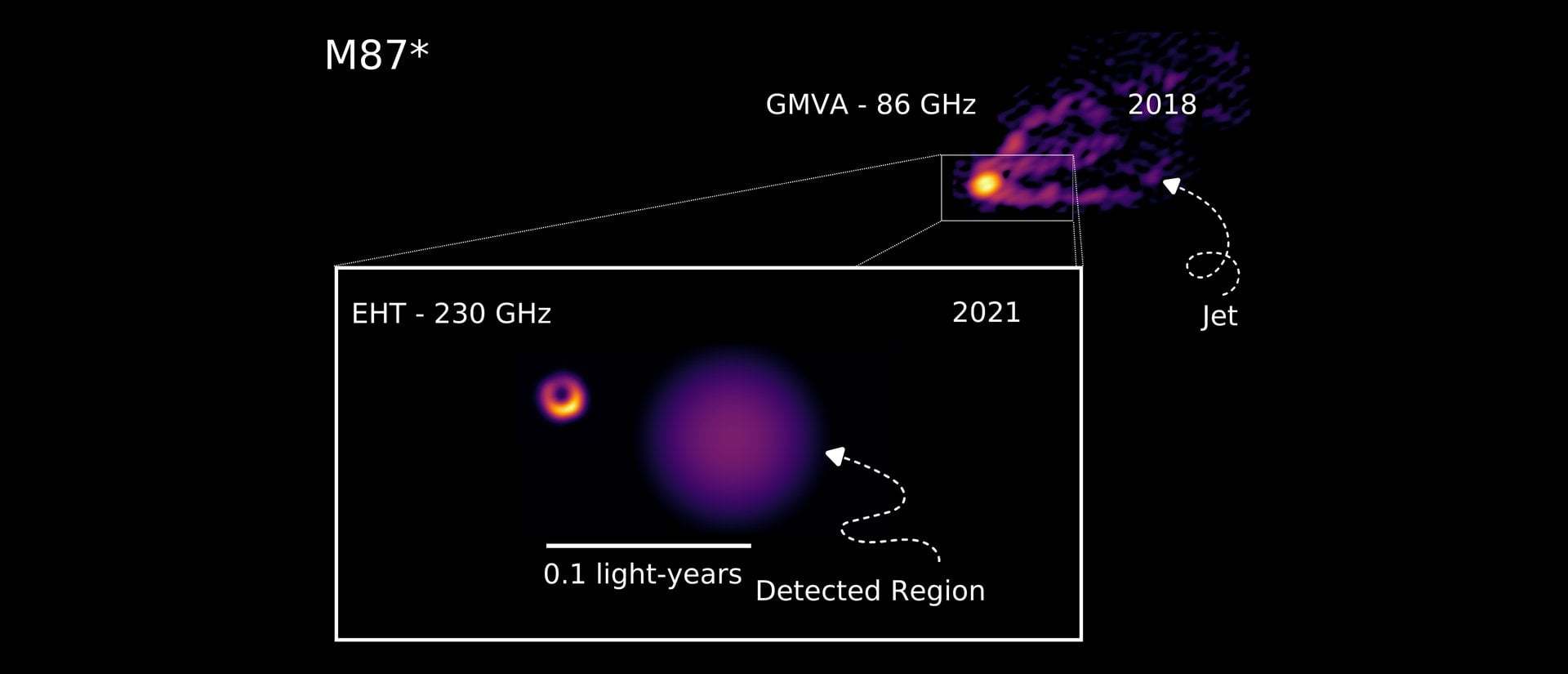

The prominent jet emanating from the poles of M87* is visible over a distance of 3,000 light-years and can be observed across the electromagnetic spectrum. The images produced by the EHT resolved the black hole's structures because they were sensitive to emissions on different scales. These are dependent on the distances between the various observatories (aka baselines) that constitute the EHT. Whereas baselines of several thousand kilometers resolved the smallest structures, shorter baselines of a few hundred kilometers revealed emissions from the extended jet.

Intermediate baselines fall between the two and were used by the team to establish a connection between the material around the black hole and the jet. "This study represents an early step toward connecting theoretical ideas about jet launching with direct observations," Saurabh said in an EHT press release. "Identifying where the jet may originate and how it connects to the black hole’s shadow, adds a key piece to the puzzle and points toward a better understanding of how the central engine operates."

By comparing the measured radio intensity on different spatial scales, they found that the luminous ring of hot gas around the black hole detected in 2019 is not the only source of detected radio emissions. Instead, the data showed that part of the missing emission is captured on intermediate baselines. While previous observations from 2017 and 2018 lacked intermediate baselines to detect the jet base, more recent data provided the necessary resolution. Combined with model calculations, Saurabh and her colleagues were able to show that an additional compact region could explain part of the missing emissions.

This region, they determined, is about 0.09 light-years from the M87* and appears to coincide with the base of the jet. Said Müller:

We have observed the inner part of the jet of M87 with global VLBI experiments for many years, with ever-increasing resolution, and finally managed to resolve the black hole shadow in 2019. It is amazing to see that we are gradually moving towards combining these breakthrough observations across multiple frequencies and complete the picture of the jet launching region.

Additional observations with the EHT are necessary to further constrain the jet's size, shape, and overall structure. These observations will allow astronomers not only to map the jet's structures but also to image them. This presents future opportunities to probe the environments of SMBHs directly and to test theories about how the laws of physics operate under such extreme conditions. "Newly observed data—now being correlated and calibrated with support from MPIfR—will soon add back the Large Millimetre Telescope in Mexico," said von Fellenberg. "This will bring an even sharper view of the jet‑launching region within reach."

Further Reading: EHT

Universe Today

Universe Today