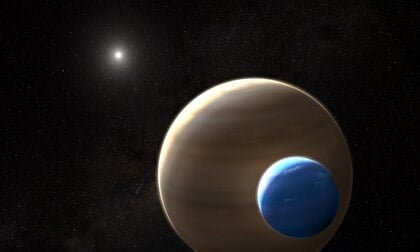

So far, humanity has yet to find its first “exomoon” - a Moon orbiting a planet outside of the solar system. But that hasn’t been for lack of trying. According to a new paper by Thomas Winterhalder of the European Southern Observatory and his co-authors available as a pre-print on arXiv, the reason isn’t because those Moons don’t exist, but simply because we lack the technology to detect them. They propose a new “kilometric baseline interferometer” that can detect moons as small as the Earth up to 200 parsecs (652 light years) away.

Moons as small as the Earth might still seem quite large, but there are almost certainly moons of that size floating somewhere in the galaxy, especially around much larger gas giant planets. So why aren’t we able to see them now? Our methodology seems to be the culprit, according to the paper.

Astronomers currently use the “transit” method, where they watch for a moon to pass in front of its parent star and cause a dip in the star’s output. While this method works well for planets, for moons it requires nearly perfect alignment - with the Earth, the star, the planet, and the moon itself all needing to be in specific places in order for us to detect it.

Fraser discusses the search for exomoons with Dr. Alex TeacheyWhat’s more, the transit method is easiest with planets / moons that are close to their parent stars. However, planets that close in on their host stars have difficulty holding onto their moons. The “Hill sphere” - i.e. the region where a planet can hold onto a moon - shrinks as the planet itself gets nearer the star. Therefore, the transit method is less than ideal to catch planets that are farther out from their star and thus more likely to have moons.

There is another planet-hunting technique, astrometry, that might be useful. This technique measures the wobble of an astronomical object, and the size and type of object that is causing that wobble. To detect planets, astronomers would watch a star to see how it moves. But for moons, astronomers would have to watch the planets themselves to see how they do.

Luckily, this technique is best done with planets that are far from their host star, and therefore have a large Hill sphere. However, current technologies, such as the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), based in Chile, are only capable of resolving wobbles of around 50 microarcseconds (µas). That is with a “baseline” of around 200 meters between the four “Unit telescopes” that comprise the VLTI.

Fraser discusses the search for exomoons with Dr. David KippingHowever, the paper suggests that, to see a reasonable number of Earth-sized moons within that 200 parsec limit would require around 1 µas of resolution. And to do that would require a much longer baseline - approximately several kilometers in fact. Interferometry works by calculating the resolution based on the wavelength of the signal being measured divided by the “baseline” - the distance between the farthest mirrors in a series of mirrors that are combined into a single system. Perhaps most famously, this type of system detected gravitational waves at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, though that system requires lasers running through a vacuum tunnel rather than just separated mirrors to collect starlight.

Speaking of mirrors, this new interferometer would work really well with another huge mirror coming online - the Extremely Large Telescope. It will have a 39 meter collector, allowing it to take direct pictures of very faint planets. In turn, the proposed new interferometer can then watch those detected exoplanets for any signs of movement which might be caused by an associated moon.

One advantage of this methodology is that it is more likely to find “habitable” exomoons, since the “Goldilocks” zone for moons around gas giants seems to be farther out in the solar system. Enceladus and Europa aren’t potentially habitable because of energy from the Sun, but from tidal heating, which warms their interior oceans, generated by their giant planet neighbors.

For now, finding a Europa or Enceladus analog in another solar system is still wishful thinking - both of those moons are likely much smaller than even the detection limit of the newly proposed interferometer. However, if we do end up building something like it, we might be able to find “giant” versions of those interesting worlds nearby. And in so doing, we might even find a potential candidate for the first habitable exoworld.

All we need to do now is actually build the telescope, which is easier said than done. While there are no concrete financials in the paper, it will likely cost a few billion dollars - about the cost of the ELT itself. While there are no forthcoming funders for this project right now, it does seem a logical next step after the ELT is complete in 2028. Maybe at that point the exomoon community can rally enough support to realize this dream project that could finally bring their sub-field into the limelight.

Learn More:

T. O. Winterhalter et al - Hunting exomoons with a kilometric baseline interferometer

UT - Tentative Exomoon Signal in HD 206893 B

UT - Finding Exomoons Using Their Host Planet's Wobble

UT - Exomoons Defy Discovery

Universe Today

Universe Today