What could force a supermassive black hole (SMBH) out of its host galaxy? They can have hundreds of millions, even billions of solar masses? What's powerful enough to dislodge one of these behemoths?

The answer lies in galaxy mergers.

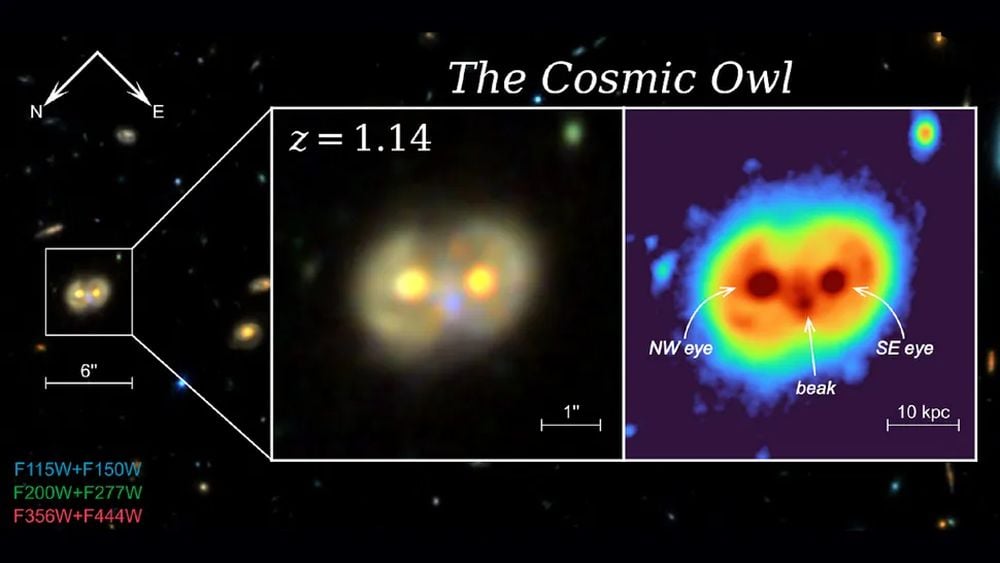

Astronomers have found what they say is the first confirmed case of a runaway SMBH. It's in the Cosmic Owl galaxy, which is actually a pair of ring galaxies about 8.8 billion light years away. The rings appear as owl eyes as they get closer and closer to merging. Astronomers observing the Cosmic Owl found a long linear feature in the galaxy and wondered if it could be the tail from the first confirmed runaway SMBH. Now, new research confirms it.

The JWST captured these images of the Cosmic Owl. Each of the "eyes" is an active galactic nuclei (AGN), and the "beak" is a stellar nursery. Image Credit: Liu et al. 2025.

The JWST captured these images of the Cosmic Owl. Each of the "eyes" is an active galactic nuclei (AGN), and the "beak" is a stellar nursery. Image Credit: Liu et al. 2025.

The new research is titled "JWST Confirmation of a Runaway Supermassive Black Hole via its Supersonic Bow Shock," and it's been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The lead author is Pieter van Dokkum from Yale's Astronomy Department. Van Dokkum is the lead author of multiple papers examining the Cosmic Owl for definitive evidence of a runaway SMBH. The research is available online at arxiv.org.

"The occasional escape of supermassive black holes (SMBHs) from their host galaxies is a long-standing prediction of theoretical studies," van Dokkum and his co-authors write. "We present JWST/NIRSpec IFU observations of a candidate runaway supermassive black hole at the tip of a 62 kpc-long linear feature at z = 0.96."

There are two channels that can give a SMBH the required quick that lets it escape its galaxy. One comes from a three-body interaction, and the other is a gravitational wave recoil caused by a BH-BH merger. "Both channels occur naturally as a result of galaxy – galaxy mergers, as the black holes of the ancestor galaxies end up in the center of the descendant," the authors write.

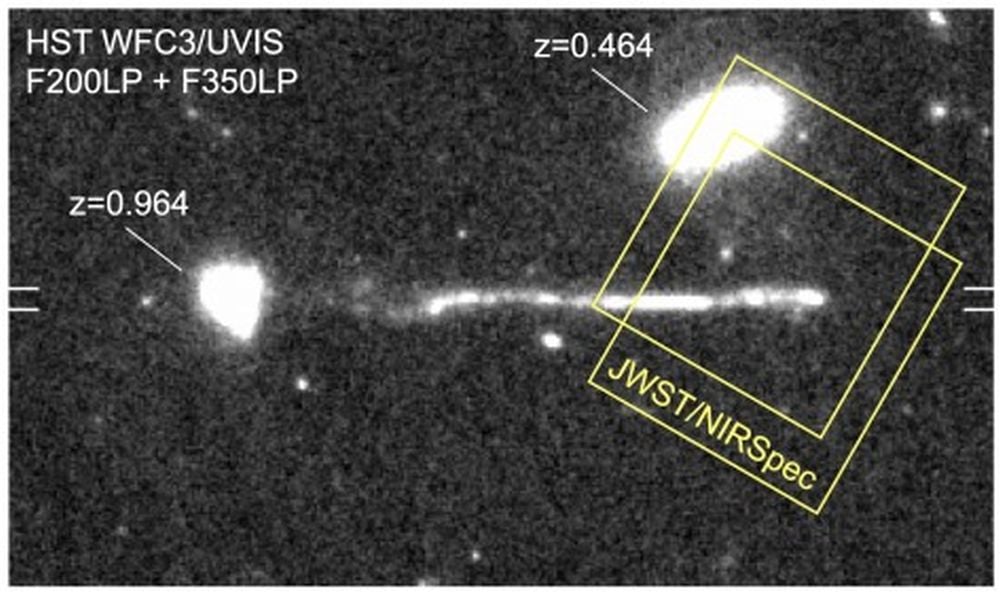

Two distinct features are involved. One is the tail, which is 200,000 light-years long, and the other is the bow shock. Pressure in the tail is lower than at the bow shock, so gas accumulates in the tail and forms new stars.

This HST image shows the tail of runaway black hole 1 (RBH1). The tail is about 62 kpc long, or about 200,000 light-years. Image Credit: van Dokkum et al. 2025.

This HST image shows the tail of runaway black hole 1 (RBH1). The tail is about 62 kpc long, or about 200,000 light-years. Image Credit: van Dokkum et al. 2025.

The JWST observed the candidate Runaway Black Hole 1 (RBH1) with its NIRSpec Integrated Field Unit. That instrument observes small patches of the sky in 3-arcsecond by 3-arcsecond cubes and captures light and spectra at the same time. It lets astronomers not only see objects, but analyze the light to determine composition, temperature, and motion at the same time.

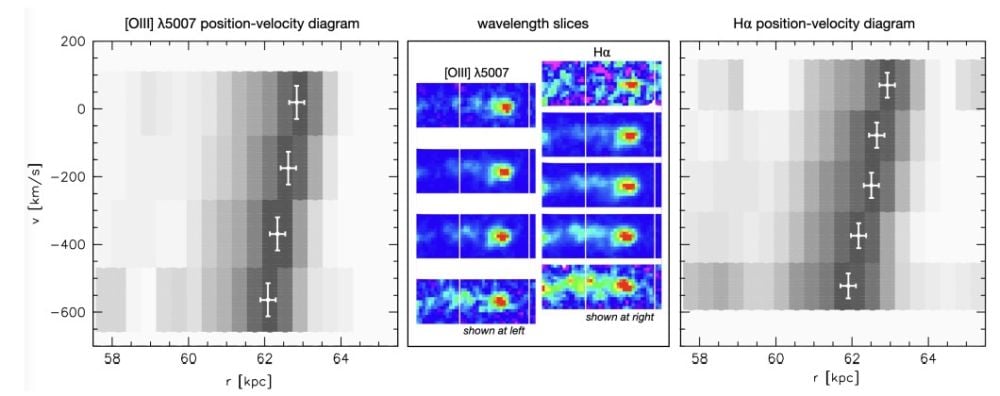

"We thus find that the observed kinematics at the tip of RBH-1 are qualitatively consistent with expectations for a strong supersonic bow shock," the authors explain. A bow shock is key evidence in support of a RBH. "The evidence for a supersonic bow shock at the head of RBH-1 is very strong, bordering on overwhelming."

This image is based on JWST observations of the OIII and H-alpha red-shifted spectral lines. Regarding the middle panel, the authors explain that "There is a striking pattern, with the emission near the tip systematically shifting further upstream for higher velocities." On the left and right are position/velocity diagrams also based on OIII and H-alpha. "These diagrams show an unambiguous gradient of ∼ 600 km s−1 over ∼ 1 kpc," the authors write. Image Credit: van Dokkum et al. 2025.

This image is based on JWST observations of the OIII and H-alpha red-shifted spectral lines. Regarding the middle panel, the authors explain that "There is a striking pattern, with the emission near the tip systematically shifting further upstream for higher velocities." On the left and right are position/velocity diagrams also based on OIII and H-alpha. "These diagrams show an unambiguous gradient of ∼ 600 km s−1 over ∼ 1 kpc," the authors write. Image Credit: van Dokkum et al. 2025.

By identifying a tail and a bow shock, the researchers have confirmed that what they're seeing is the first confirmed runaway black hole. In a previous paper, they identified these features but lacked the detailed evidence to confirm that what they were seeing is a RBH. New JWST and HST observations are largely responsible for the confirmation, with the JWST playing the leading role.

"The central proposal of Paper I was that the linear feature is the wake behind a runaway supermassive black hole, and this is strongly supported by our analysis," the authors write. "Using newly obtained HST/UVIS and JWST/NIRSpec data we confirm that the remarkable linear feature reported in Paper I is the wake behind a runaway SMBH.|"

"We also confirm the presence of a spatially-resolved bow shock at the head of the wake, something that we predicted based on shock models and the luminosity of the [O III] knot in the Keck/LRIS data," the authors write in their conclusion.

It's been 50 years since scientists predicted that SMBHs can go rogue because of gravitational wave recoil or three-body interaction. Finding the first one is always a triumph of determination and intellectual skill, but where there's one there are likely to be others. Finding them will be the job of upcoming telescopes.

"The obvious data sets to look for these features in a systematic way are wide-field surveys with Euclid and Roman," the authors conclude.

The Universe can seem like an awfully strange and threatening place sometimes, and this discovery won't assuage any fears. Though we're in no way in any danger at all, it's a terrible realization that supermassive black holes with tens of millions of solar masses can be blasting through space, compressing everything in front of them and trailing a stream of gas and new stars.

Universe Today

Universe Today