When Edwin Hubble revealed in the 1920s that distant galaxies were retreating from us in all directions, he laid the foundation for our understanding of the expansion of the universe. But even then, the picture wasn't quite clean. Some nearby galaxies, like Andromeda, were moving toward us rather than away, exactly what you'd expect from gravity between neighboring galaxies.

Yet most other large galaxies in our neighborhood presented a puzzle. Despite the substantial combined mass of the Milky Way, Andromeda, and dozens of smaller galaxies forming what's called the Local Group, these neighbours seemed oddly unaffected. They receded from us following the smooth Hubble-Lemaître expansion law as if our local gravitational pull didn't matter at all. For fifty years, astronomers wondered why the gravity of the Local Group's isn’t disturbing the expansion pattern of nearby galaxies?

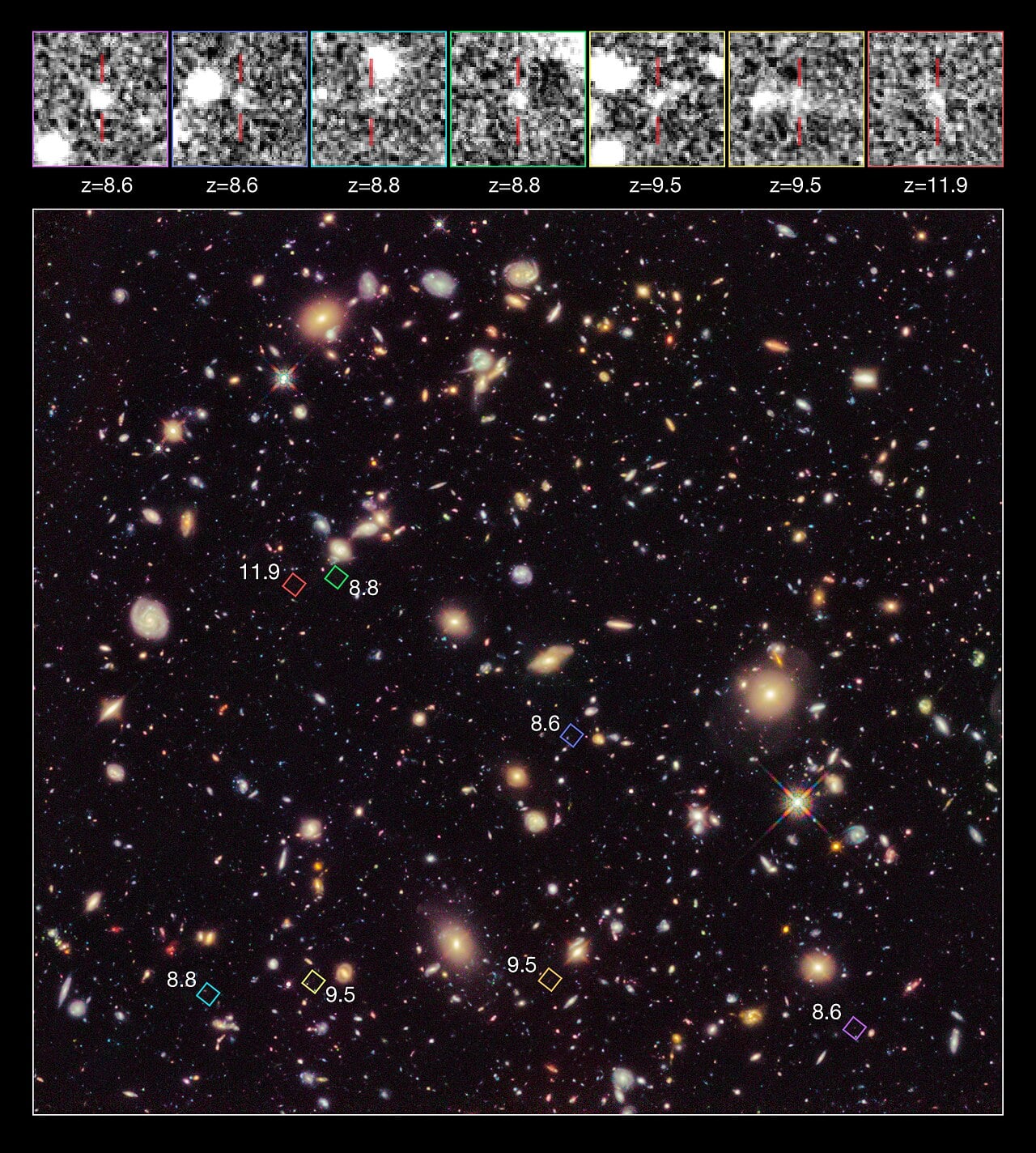

The Andromeda Galaxy is a member of the Local Group of galaxies and unlike the large scale expansion, is moving toward our own Milky Way Galaxy (Credit : Brody Wesner)

The Andromeda Galaxy is a member of the Local Group of galaxies and unlike the large scale expansion, is moving toward our own Milky Way Galaxy (Credit : Brody Wesner)

An international team led by Ewoud Wempe from the Kapteyn Institute in Groningen has cracked the case using sophisticated computer simulations. The solution involves the three dimensional architecture of matter around us including both the visible galaxies and the invisible dark matter surrounding them.

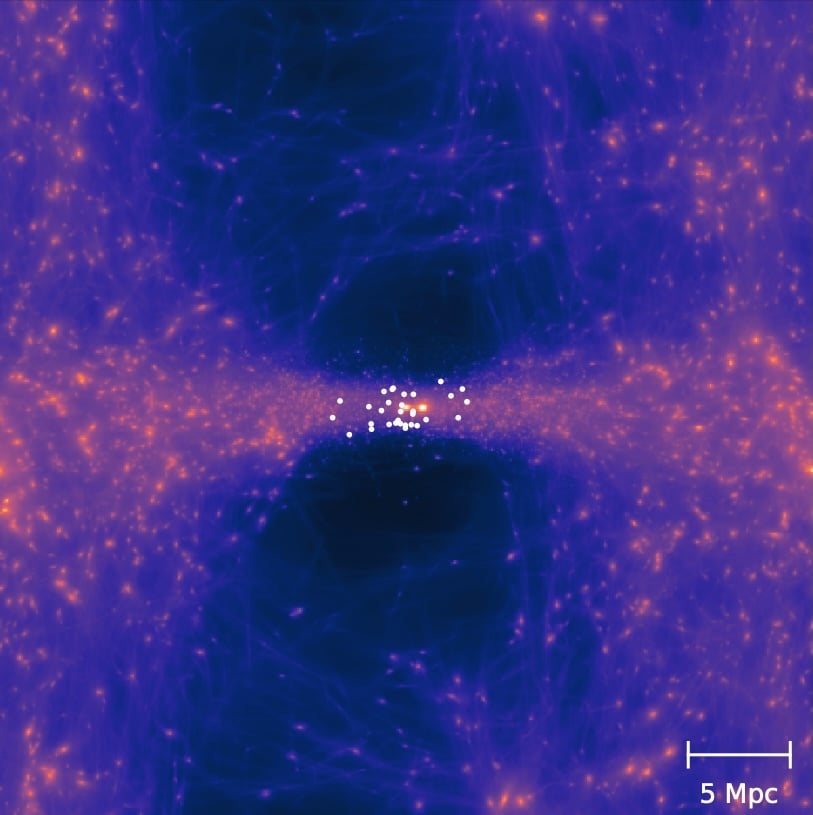

The mass distribution just beyond the Local Group, it turns out, isn't spherical or random. Instead, it's organised into a vast, flat sheet extending tens of millions of light years across. Above and below this sheet lie enormous voids, regions nearly empty of galaxies.

To find this solution, the team created "virtual twins" of our local galactic environment. Their algorithm started with conditions in the early universe based on observations of the cosmic microwave background, then used powerful computers to evolve these conditions forward to the present day. The simulations had to reproduce specific constraints namely the masses, positions, and velocities of the Milky Way and Andromeda, plus the positions and velocities of 31 galaxies surrounding the Local Group.

When the simulations successfully recreated our local environment, they revealed something remarkable. The nearby galaxies moving away from us sit embedded in a large scale sheet of dark matter. This geometry explains why they follow the Hubble expansion so cleanly despite our gravity.

The researchers identified two key factors at work. First, for galaxies within the sheet, the Local Group's gravitational pull toward us is counteracted by mass distributed further away in the plane pulling in other directions. The forces largely cancel out, leaving these galaxies free to follow the general expansion of the universe.

Second, the regions where you'd expect to see matter falling toward us, the voids above and below the sheet are effectively invisible because galaxies simply don't form there. We can't see deviations from smooth expansion in places where there's nothing to observe.

Computer simulations carried out by astronomers from the University of Groningen in collaboration with researchers from Germany, France and Sweden show that most of the (dark) matter beyond the Local Group of galaxies (which includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy) must be organised in an extended plane. Above and below this plane are large voids (Credit : University of Groningen)

Computer simulations carried out by astronomers from the University of Groningen in collaboration with researchers from Germany, France and Sweden show that most of the (dark) matter beyond the Local Group of galaxies (which includes the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy) must be organised in an extended plane. Above and below this plane are large voids (Credit : University of Groningen)

Wempe describes this as the first assessment of dark matter's distribution and velocity in the region surrounding the Milky Way and Andromeda. The team explored all possible configurations of the early universe that could evolve into our current Local Group setup, searching for solutions consistent with both cosmological theory and observed local dynamics.

Co-researcher Amina Helmi notes that astronomers have attempted to solve this problem for decades without success. She's excited that purely from galaxy motions, they can now determine a mass distribution matching both the positions of galaxies within the Local Group and those just outside it.

The work elegantly resolves a tension between local observations and universal expansion. Our neighborhood isn't exempt from gravitational physics, it's just that the particular geometry of mass around us creates an environment where expansion and gravity happen to balance in an unusually smooth way.

It's another reminder that structure of the universe isn't random. The universe organises matter into walls, filaments, and voids on the largest scales, and these structures shape how galaxies move and interact. Sometimes, understanding what happens in our own backyard requires mapping the architecture of the entire neighborhood.

Source : The Milky Way is embedded in a ‘large-scale sheet’ and this explains the motions of nearby galaxies

Universe Today

Universe Today