Aging stars can completely destroy their planets.

When a star reaches the end of its life on the main sequence, it goes through dramatic changes. And those changes don't just dictate the star's fate; they can also dictate what happens to any planets that are orbiting these stars. They face a bleak future as the star's tidal force rips them apart and the intense heat vapourizes them.

It happens because main sequence stars eventually run out of hydrogen and expel their outer layers. The loss of all this mass weakens the star's gravitational hold on itself. It swells up and can consume or destroy nearby planets. This is what the Sun will eventually do, though not for billions of years yet.

But depending on the star and its solar system architecture, some planets can survive the destructive swelling of their host. When our Sun nears the end and becomes a red giant, it will engulf the inner planets, maybe Earth too. Mars' fate is unclear. The gas giants have the best survival odds.

*This illustration shows a swollen red giant star with its substellar companion in the foreground. When main sequence stars swell into red giants, they can destroy any nearby planets. But depending on circumstances, some gas giants can survive. Image Credit: ESO/L. Calçada*

*This illustration shows a swollen red giant star with its substellar companion in the foreground. When main sequence stars swell into red giants, they can destroy any nearby planets. But depending on circumstances, some gas giants can survive. Image Credit: ESO/L. Calçada*

In 2011, astronomers found an exoplanet with about 8 Jupiter masses orbiting a white dwarf. It's on an extremely wide orbit and was separated from the star by about 2,500 au when it was observed. At this distance, the star couldn't touch it.

In 2020, astronomers discovered a Jupiter-sized gas giant around a white dwarf. It's on a tight orbit and researchers think it migrated inward after the star transitioned to a white dwarf. It never would've survived the star's red giant phase if it was this close at the time.

This pair of exoplanets represents the two pathways that Jupiter-mass planets can follow to survive around a white dwarf. They're either so far away they're basically unaffected, or else they're far away enough to survive then migrate inward.

But how many of these gas giants are out there orbiting white dwarfs? Why do astronomers observe so few of them? Are they really rare, or is there a detection bias at work?

New research to be published in Astronomy and Astrophysics examines the population of gas giants orbiting white dwarfs. It's titled "Predicted incidence of Jupiter-like planets around white dwarfs," and the lead author is Alex Mauch-Soriano. Mauch-Soriano is from the Departamento de Física, Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María, in Valparaíso, Chile.

"Only a handful of gas giant planets orbiting white dwarfs are known," the authors write. "It remains unclear whether this paucity reflects observational challenges or the consequences of stellar evolution." To find out, the researchers synthesized a population of white dwarfs and their substellar companions. They used stellar-evolution codes based on things like mass loss and stellar tides to predict what the population would look like.

"We find that the predicted fraction of white dwarfs hosting substellar companions in the Milky Way is, independent of uncertainties related to initial distributions, stellar tides, or stellar mass loss during the asymptotic giant branch, below ~3%," the researchers write.

These few hardy survivors share some characteristics regarding the white dwarf mass, the age of the system, the orbital separation, and the type of companion, either gas giant or brown dwarf.

More Jupiter-like exoplanets survive when their white dwarfs have lower masses, meaning the progenitor stars had lower masses, too. Survival peaks when the white dwarf has between 0.53-0.66 solar masses. As a general rule, the Initial-Final Mass Relation (IFMR) says the progenitor's initial mass had to be between 1 and 3 solar masses.

Younger star systems also have more planetary survivors. In systems between 1 and 6 billion years old, the occurrence rate of gas giants is more than 3%.

Not surprisingly, orbital separation had a powerful effect on outcomes. Surviving companions orbit between 3 and 24 au.

The surviving planets in the synthesized population were overwhelmingly gas giants as opposed to brown dwarfs. About 95% are gias giants.

The researchers explain that the metallicity of the progenitor star has a powerful effect on surviving planets because progenitors with higher metallicities simply form more planets. "Owing to the strong dependence of companion occurrence on the metallicity of the white dwarf progenitor, the assumed age-metallicity relation strongly affects the predictions," the researchers explain. "Based on recent estimates of the local age-metallicity relation, we estimate that the fraction of white dwarfs with companions close to the Sun might reach ~8%."

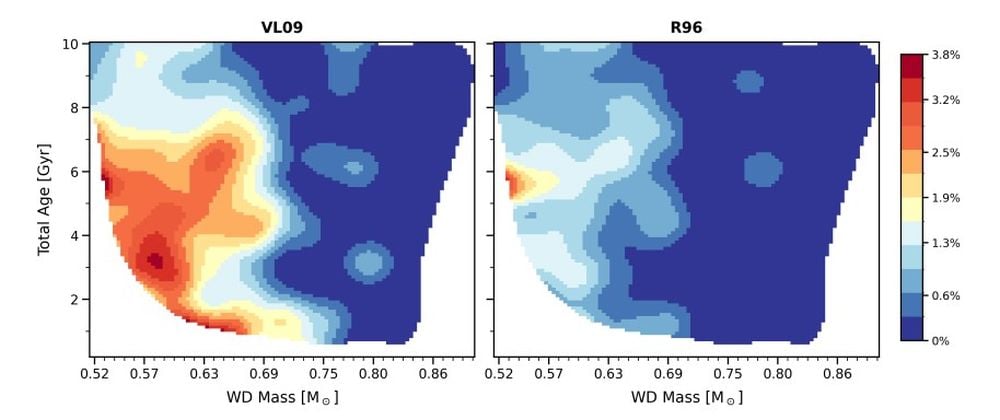

The researchers used two different tidal regimes that are standards in astronomy. One involves weak tides, and the other invoves stronger tides. This obviously has an effect on outcomes, since tides can tear gas giants apart. "To some extent, the properties of the surviving companion population are shaped by the adopted tidal prescription," they write. "The fraction of companions that survive the stellar evolution of their host star is roughly two times higher when adopting the weaktides prescription of Villaver & Livio (2009) compared to the strong stellar tides suggested by Rasio et al. (1996),"the authors explain. "Stronger tides generally require companions to be initially located at somewhat larger semimajor axes and to orbit less massive stars in order to survive."

*These panels represent weak tides (left) and strong tides (right), which greatly affect surviving gas giants. The x-axis shows WD mass and the y-axis shows age in billions of years. The coloured scale on the right shows gas giant survival percentages. More gas giants survive in weak tides than in strong tides, obviously. The authors point out that even a small increase in tidal strength under the strong tide scenario would wipe out the small island of probability in the right panel. Image Credit: Mauch-Soriano et al. 2026. A&A*

*These panels represent weak tides (left) and strong tides (right), which greatly affect surviving gas giants. The x-axis shows WD mass and the y-axis shows age in billions of years. The coloured scale on the right shows gas giant survival percentages. More gas giants survive in weak tides than in strong tides, obviously. The authors point out that even a small increase in tidal strength under the strong tide scenario would wipe out the small island of probability in the right panel. Image Credit: Mauch-Soriano et al. 2026. A&A*

Synthesizing a population based on everything we know about the population is one thing. But observing these planets is a completely different endeavour, and confirming this percentage is daunting. "The potential to directly detect the predicted companions through imaging will depend on the age of the WD, the total age of the system, and the orbital separation, which converts to the required contrast and angular resolution of the chosen observing facility," the researchers explain.

The results suggest that our scarce detections of white dwarf substellar companions is not simply due to observational challenges. Instead, the low number of detections reflects the true low survival rate for planets in this precarious position.

Universe Today

Universe Today