One of the most consequential events—maybe the most consequential one throughout all of Earth's long, 4.5 billion year history—was the Great Oxygenation Event (GOE). When photosynthetic cyanobacteria arose on Earth, they released oxygen as a metabolic byproduct. During the GOE, which began around 2.3 billion years ago, free oxygen began to slowly accumulate in the atmosphere.

It took about 2.5 billion years for enough oxygen to accumulate in the atmosphere for complex life to arise. Complex life has higher energy needs, and aerobic respiration using oxygen provided it. Free oxygen in the atmosphere eventually triggered the Cambrian Explosion, the event responsible for the complex animal life we see around us today.

This is a fairly well-understood process in Earth's history, but does it happen on other worlds? Can it happen on planets orbiting dim red dwarfs? Red dwarfs (M dwarfs) are the most plentiful star type in the Milky Way, so they host the most exoplanets. They're known to host rocky, Earth-like worlds, and exoplanet scientists are keen to understand if these plentiful planets can, in fact, host life.

The question is, do red dwarfs emit enough radiation to power photosynthesis that can trigger a GOE on planets orbiting them?

New research tackles this question. It's titled "Dearth of Photosynthetically Active Radiation Suggests No Complex Life on Late M-Star Exoplanets," and has been submitted to the journal Astrobiology. The authors are Joseph Soliz and William Welsh from the Department of Astronomy at San Diego State University. Welsh also presented the research at the 247th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, and the paper is currently available at arxiv.org.

"The rise of oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere during the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) occurred about 2.3 billion years ago," the authors write. "There is considerably greater uncertainty for the origin of oxygenic photosynthesis, but it likely occurred significantly earlier, perhaps by 700 million years." That timeline is for a planet receiving energy from a Sun-like star.

But what about for a planet that receives only what a dim, red dwarf provides? What does the timeline look like, and is it even possible?

"Assuming this time lag is proportional to the rate of oxygen generation, we can estimate how long it would take for a GOE-like event to occur on a hypothetical Earth-analog planet orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1 (a late M star with Teff 2560 K)," the authors explain.

It boils down to photons. The weak flow of dim, red photons coming from red dwarfs are far less energetic than the flood of photons that come from Sun-like stars. Do they provide enough energy for photosynthesis?

To find out, the researchers looked at the well-known TRAPPIST-1 system. It's a cool red dwarf about 40 light-years away with seven Earth-sized rocky exoplanets, three of which are in the star's habitable zone. One of them, TRAPPIST-1e, is particularly interesting. Its size and its orbit make it quite Earth-like.

There's nowhere near enough evidence to show that the planet can harbour any type of life, but in this research, the authors asked a clever question. What would Earth be like if it was in the place of TRAPPIST-1e? "Essentially we are asking the question, “What would happen if we replaced TRAPPIST-1e with the Archean Earth?”" the authors write.

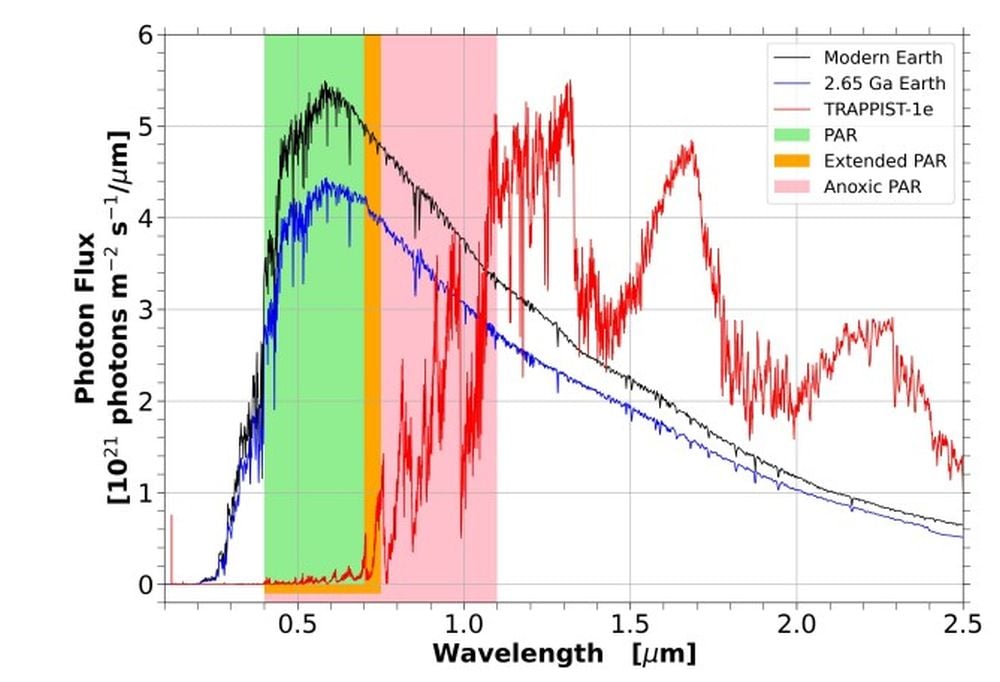

"Although in the habitable zone, an Earth-analog planet located in TRAPPIST-1e's orbit would receive only 0.9% of the Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) that the Earth gets from the Sun," the authors write. "This is because most of the star's light is emitted at wavelengths longer than the 400-700 nm PAR range. Thus it would take 63 Gyrs for a GOE to occur."

This figure shows the incident photon flux density for the modern-day Earth (black), Archean Earth at 2.65 Ga (blue), and TRAPPIST-1e (red). The spectral resolution has been reduced for clarity. The shaded regions represents three relevant bandpasses for photosynthesis: standard PAR (0.40-0.70 µm), extended PAR (0.40-0.75 µm), and anoxic PAR (0.40-1.1 µm). Image Credit: Soliz and Welsh 2025.

This figure shows the incident photon flux density for the modern-day Earth (black), Archean Earth at 2.65 Ga (blue), and TRAPPIST-1e (red). The spectral resolution has been reduced for clarity. The shaded regions represents three relevant bandpasses for photosynthesis: standard PAR (0.40-0.70 µm), extended PAR (0.40-0.75 µm), and anoxic PAR (0.40-1.1 µm). Image Credit: Soliz and Welsh 2025.

63 billion years is far longer than the current age of the Universe, so the conclusion is clear. There simply hasn't been enough time for oxygen to accumulate on any red dwarf planet and trigger the rise of complex life, like happened on Earth with the GOE.

But the situation improves slightly when the researchers consider more detail.

"But the linear assumption is problematic; as light levels increase, photosynthesis saturates then declines, an effect known as photoinhibition. Photoinhibition varies from species to species and depends on a host of environmental factors," the authors write. "There is also sensitivity to the upper wavelength limit of the PAR: extending just 50 nm increases the number of photons by a factor of 2.5."

When the researchers took this and other factors into account, the timescale for a red dwarf GOE was reduced considerably: between one billion and five billion years.

But there's still one problem. Some photosynthetic bacteria are non-oxygenic. That means that although they use photosynthesis to convert sunlight to metabolic energy, they don't produce oxygen. And they need much less light. "However, non-oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria can thrive in low-light environments and can use near-IR light out to 1100 nm, providing 22 times as many photons," the researchers explain.

This is a massive advantage over oxygenic photosynthetic bacteria like cyanobacteria. Organisms compete with one another, and that advantage could shape the future of life on exoplanets around dim red dwarfs. "Because anoxygenic evolved before oxygenic photosynthesis, there would have been direct competition for light and nutrients," the authors write.

"With this huge light advantage, and because they evolved earlier, anoxygenic photosynthesizers would likely dominate the ecosystem," the researchers explain. "On a late M-star Earth-analog planet, oxygen may never reach significant levels in the atmosphere and a GOE may never occur, let alone a Cambrian Explosion. Thus complex animal life is unlikely."

*This artist's image illustrates the Cambrian Explosion, when complex life appeared and flourished on Earth. Image Credit: Mesa Shumacher/Santa Fe Institute*

*This artist's image illustrates the Cambrian Explosion, when complex life appeared and flourished on Earth. Image Credit: Mesa Shumacher/Santa Fe Institute*

The conclusion is based on some necessary assumptions. One is that oxygen is necessary for complex life. Another is that life would arise on this hypothetical exoplanet on a timeline similar to Earth's. The authors point out several other assumptions, but also note that nearly all of these unknown factors scale out of the problem. That means they affect the timeline, but don't contradict the overall conclusion.

"While we are not assuming that the path that life takes on this hypothetical world would be identical to what occurred on Earth (even if we rewound and played Earth’s history over we do not believe it would be the same), but we do make the assumption that the timescales are roughly similar," the researchers explain. "Importantly, factors of tens of percent in the estimated timescales do not alter the conclusions."

The authors conclude that this hypothetical planet would most likely be dominated by light-starved microbial mats that grow ever so slowly in shallow water or damp environments, with no competitors.

But we just don't know for sure yet how much complex life could be different on exoplanets compared to on Earth, and the authors acknowledge that. "Finally, if future work shows we are incorrect, i.e., abundant oxygen is found in a late M-dwarf exoplanet’s atmosphere, this would be extremely exciting. It would suggest that life has found a way to carry out oxygenic photosynthesis by combining several NIR photons - an astonishing feat," the researchers conclude.

There's a lot of research into and debate about red dwarf habitability. Most of it centers on red dwarf flaring. These stars may exhibit flaring powerful enough to strip away the atmospheres of any exoplanets in their habitable zones.

But as this research shows, the simple weakness of these stars' stellar output may prohibit complex life completely. In that case, whether they could maintain an atmosphere or not becomes less relevant.

Universe Today

Universe Today