Omega Centauri dominates the southern sky as the Milky Way's largest and brightest globular cluster, a dense sphere containing roughly ten million stars. Earlier this year, astronomers found evidence that an intermediate mass black hole hides within the cluster's core, revealed by seven stars moving far too quickly to remain bound unless something massive holds them gravitationally. Now researchers have searched for the black hole itself using radio telescopes, and their discovery is what they didn't find.

Intermediate mass black holes represent a missing link in our understanding of how black holes evolve. We know stellar mass black holes form from dying stars, with masses up to perhaps 200 times the Sun. We know supermassive black holes weighing millions or billions of solar masses dominate galactic centres. But intermediate mass black holes, with masses between these extremes, remain frustratingly rare. Only a handful of candidates exist, and confirming them proves difficult.

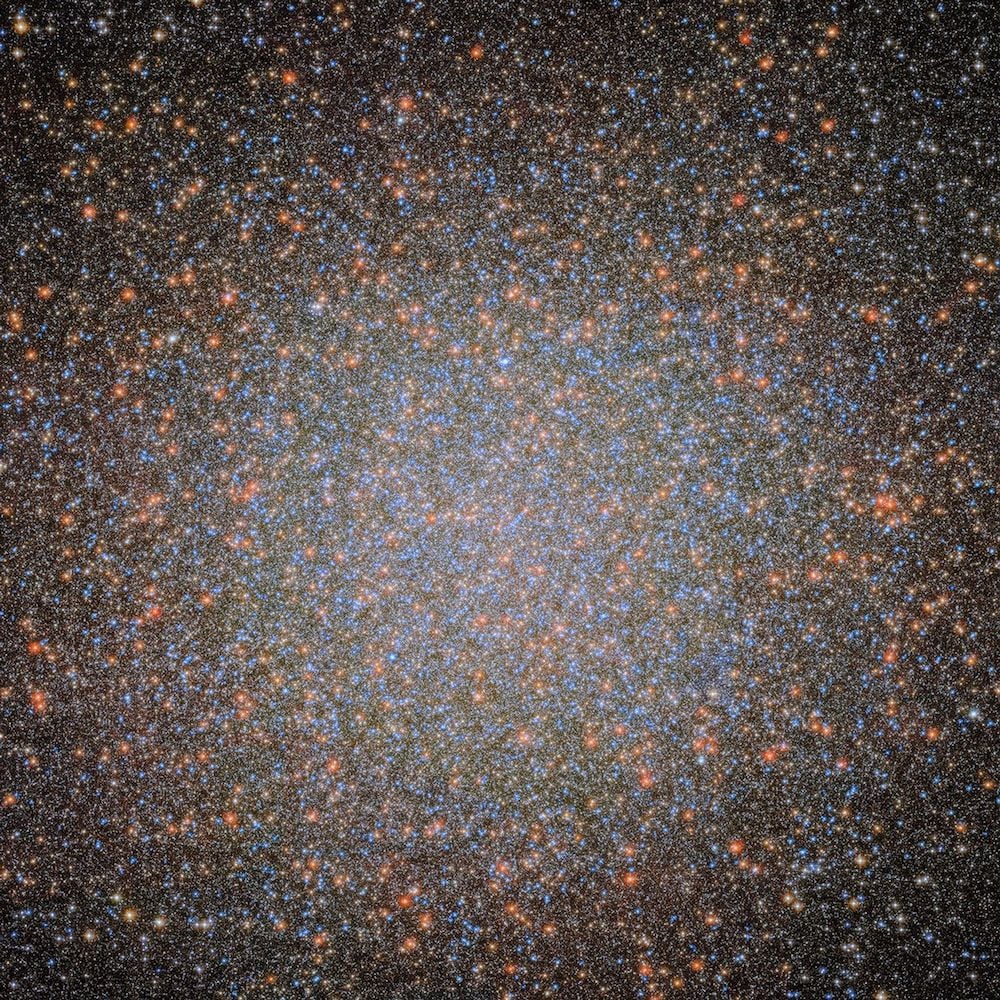

Omega Centauri (Credit : NASA)

Omega Centauri (Credit : NASA)

The recent Hubble Space Telescope study tracked 1.4 million stars in Omega Centauri across two decades of observations. Seven stars in the cluster's innermost region move so rapidly they should escape entirely, yet remain bound. The gravitational pull keeping them corralled suggests a black hole with at least 8,200 solar masses, though estimates reach as high as 47,000 solar masses.

Angiraben Mahida and colleagues decided to search for the black hole's accretion signature. When black holes feed on surrounding gas and dust, the material forms a hot accretion disk that emits across the electromagnetic spectrum, including radio waves. The team used the Australia Telescope Compact Array to observe Omega Centauri's central region for approximately 170 hours, achieving a sensitivity of 1.1 microjanskys at 7.25 gigahertz. This represents the most sensitive radio image of the cluster ever obtained.

Five antennas of the Australia Telescope Compact Array, near Narrabri, New South Wales (Credit : CSIRO)

Five antennas of the Australia Telescope Compact Array, near Narrabri, New South Wales (Credit : CSIRO)

They found nothing. No radio emission appears at any of the proposed cluster centres where the black hole should reside.

The non-detection places constraints on the black hole's behaviour. Using the fundamental plane of black hole activity, which relates a black hole's mass, radio luminosity and X-ray luminosity, the team calculated that any intermediate mass black hole in Omega Centauri must have exceptionally low accretion efficiency. The upper limit stands at roughly 0.004, meaning less than half a percent of infalling material's rest mass energy converts to radiation.

This extreme quietness isn't entirely surprising. Omega Centauri likely represents the stripped core of a dwarf galaxy consumed by the Milky Way billions of years ago. The cluster's central regions may simply lack sufficient gas for the black hole to accrete. Unlike the gas rich environments surrounding supermassive black holes in active galaxies, or the stellar companions feeding stellar mass black holes, this intermediate mass black hole appears to exist in a relative desert, starved of fuel and consequently silent across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Source : No evidence for accretion around the intermediate-mass black hole in Omega Centauri

Universe Today

Universe Today