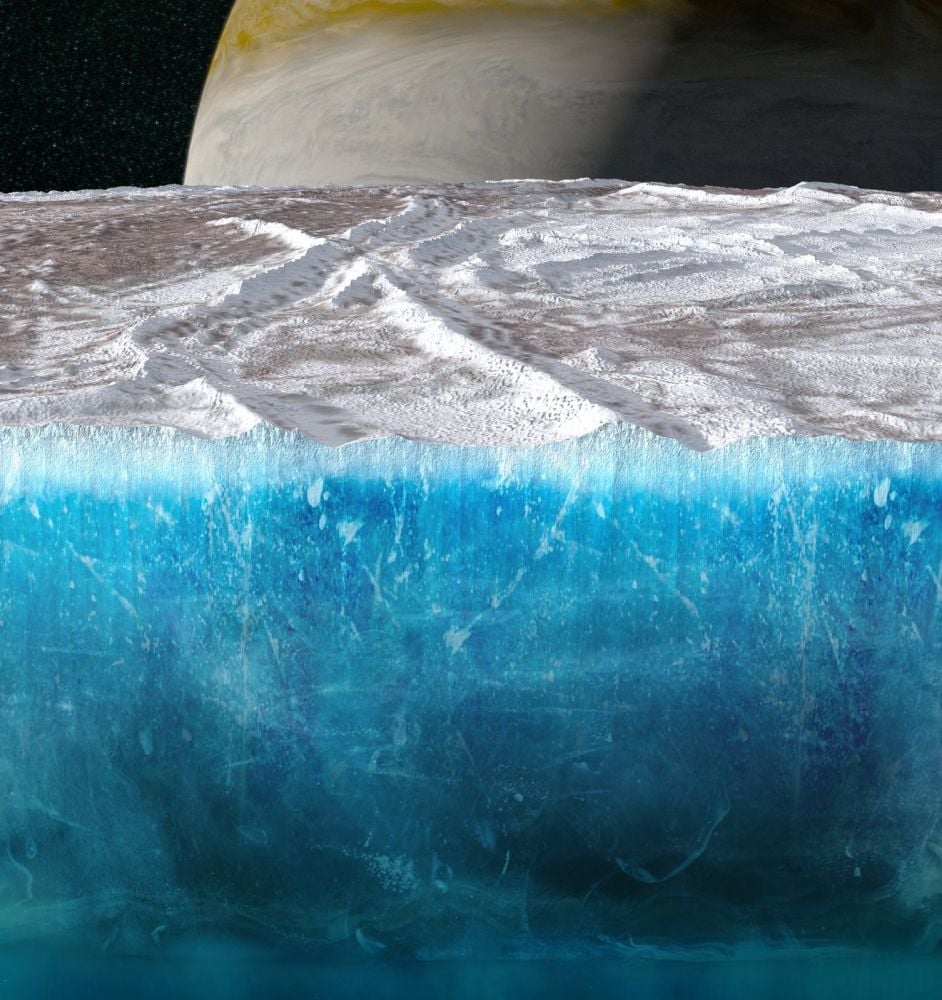

Observations show that Jupiter's icy moon Europa has a thick icy shell covering a warm ocean. The ocean is chemically-rich, and may have all the essential ingredients for life. That's why Europa is such a juicy target in the search for life, and why NASA's Europa Clipper and the ESA's JUICE are on their way to examine the moon in greater detail.

Speculation that Europa may have an ocean goes back to the Voyager missions. Images from those spacecraft showed a cracked icy surface, leading some scientists to wonder if it had a subsurface ocean. The Galileo mission provided more evidence that Europa wasn't completely frozen. The Hubble space telescope also bolstered the idea when it observed plumes erupting through the moon's ice, which could be escaping water.

However tantalizing these observations are, they represent only the beginning of understanding the intriguing moon. There are outstanding questions that need to be answered before the habitability hypothesis can be advanced. One question concerns the thickness of Europa's icy shell, as well as the fissures and cracks in it.

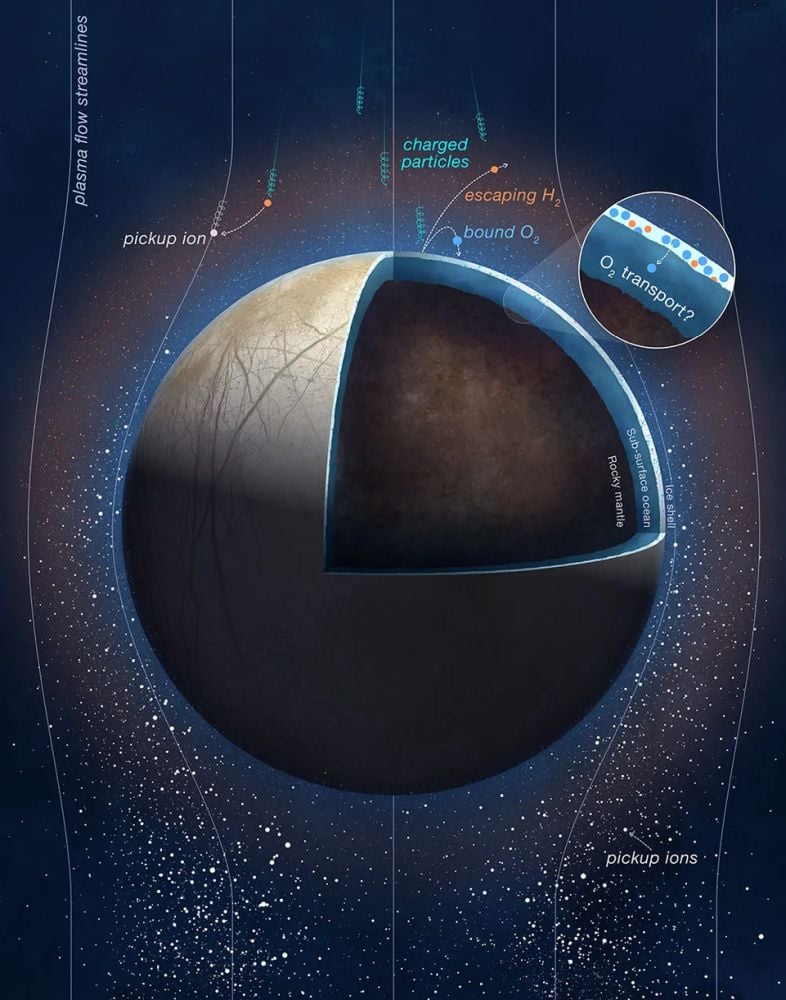

Scientists think that for Europa's ocean to support life, there needs to be a pathway through the ice that lets the ocean and the surface "communicate" chemically. Europa's surface is bombarded by Jupiter's powerful radiation, and that energy drives chemical reactions. This can produce antioxidants and other chemicals conducive to life. If the ice is thin, or if there are fissures that act as chemical pathways, these substances could reach the ocean.

*Charged particles from Jupiter strike Europa's surface, where they split frozen water molecules apart. Scientists think some of the freed oxygen finds its way through the ice into the moon's subsurface ocean, where it enables life. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SWRI/PU*

*Charged particles from Jupiter strike Europa's surface, where they split frozen water molecules apart. Scientists think some of the freed oxygen finds its way through the ice into the moon's subsurface ocean, where it enables life. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SWRI/PU*

While the Europa Clipper and JUICE are years away from reaching Europa, NASA does have a spacecraft studying the Jovian system: Juno. It's been studying Jupiter and its Galilean moons for almost ten years now. While its priority target is Jupiter, the spacecraft took several opportunities to aim its instruments at the gas giant's moons.

Recent research in Nature Astronomy presents the results of some of Juno's observations of Europa. It's titled "Europa’s ice thickness and subsurface structure characterized by the Juno microwave radiometer." The lead author is Steve Levin, Juno project scientist and co-investigator from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

"Jupiter’s moon Europa is thought to harbour a saltwater ocean beneath a variously disrupted ice shell, and it is, thus, one of the highest priority astrobiology targets in the Solar System," the authors write. "Estimates of the ice-shell thickness range from 3 km to over 30 km, and observations by the Galileo spacecraft indicated widespread regions of ice disruption (chaotic terrain) leading to speculation that the ice shell may contain subsurface cracks, faults, pores or bubbles."

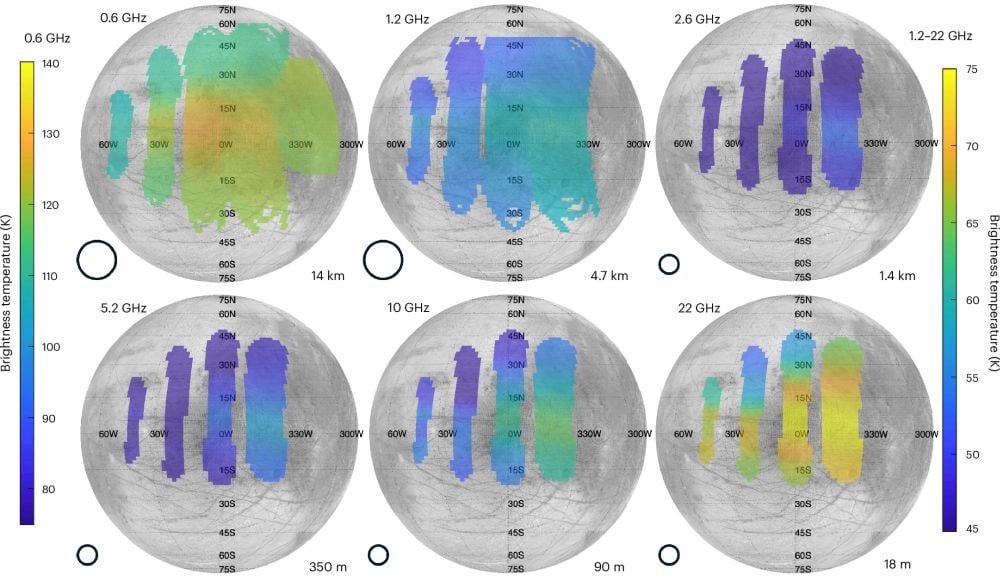

To make headway on the issue, scientists probed Europa with Juno's Microwave Radiometer (MWR). The MWR has six different antennae that each monitor a separate MW frequency. The six were chosen because they can pierce Jupiter's thick atmosphere, giving the mission a way to measure the gas giant's temperature at different atmospheric levels and create a depth profile. In a similar way, the MWR can measure ice temperatures at different levels of Europa's icy sheet.

The MWR took measurements that can place constraints on Europa's ice thickness. Current estimates range from 3 km to 30 km thick, which is a very wide range.

The MWR instrument measured ice temperatures ranging from only several meters deep to several kilometers deep, with each frequency measuring a different depth. By piecing them together, the researchers created a temperature profile for the ice, which paints a picture of its thickness. These measurements not only tighten up our understanding of Europa's shell thickness, they also shed light on the nature of its cracks and fissures, which create reflections when probed.

"These observations of ice temperature versus depth include evidence of frequency-dependent scattering in the ice, and they provide constraints on the thickness of the ice shell along with the size and depth of sources of the observed reflections," the authors explain.

This figure shows the six maps obtained from Juno's MWR observations. Circles at the bottom left of each image show beam size, and the number on the bottom right is the approximate sounding depth if the ice were 50% water. Image Credit: Levin et al. 2025. NatAstr.

This figure shows the six maps obtained from Juno's MWR observations. Circles at the bottom left of each image show beam size, and the number on the bottom right is the approximate sounding depth if the ice were 50% water. Image Credit: Levin et al. 2025. NatAstr.

The salinity of the ice isn’t known, so when the researchers modelled their results, they began with a baseline assumption that the ice was pure water.

"For the idealized case of pure water ice, the data are consistent with the existence of a thermally conductive ice shell with a thickness of 29 ± 10 km and with the presence of cracks, pores or other scatterers extending to depths of hundreds of metres below the surface with a characteristic size smaller than a few centimetres in radius," the researchers explain.

It could be even thicker, depending on its salinity, or if it has and additional warmer layer.

“The 18-mile estimate relates to the cold, rigid, conductive outer-layer of a pure water ice shell,” said lead author Levin in a press release. “If an inner, slightly warmer convective layer also exists, which is possible, the total ice shell thickness would be even greater. If the ice shell contains a modest amount of dissolved salt, as suggested by some models, then our estimate of the shell thickness would be reduced by about 3 miles.”

Ice this thick is a more impervious chemical barrier. If the cracks or pores are only a few centimeters in radius, and they only extend a few hundred meters into the ice, the picture looks even more bleak.

These results put a damper on Europa's habitability enthusiasm. Other research also shows that the plumes observed coming from Europa may not come from its ocean. Instead, they could come from pockets of water trapped in voids or cracks in its ice. So the purported connection between the ocean and the surface may be only tentative, even non-existent.

Does a lack of a chemical pathway doom Europa to inhabitability? Not necessarily. But this pathway may be the only way for surface chemicals and nutrients to reach the ocean. Life could still persist, but it would have to lean heavily on tidal heating and hydrothermal vents, and its primordial ocean would've had to have been seeded with nutrients when it formed. Still, without an active exchange between the surface and the ocean, it's difficult to see how life could survive once the ocean's nutrients were consumed.

The researchers point out that there are some sticking points in their research. For one, their measurments aren't global. "We note that our results are limited to the terrain observed, and further mapping of Europa’s surface by radiometry or radar may reveal regions where the ice shell is thinner or thicker or contains unobserved variations in the regolith," they explain.

Also, their ice shell thickness estimates rest on some assumptions about the ice's purity. "Impurities in the ice, such as salts or other materials, would increase the microwave opacity, potentially reducing the depth sounded by all channels and, therefore, reducing the difference in depth between the 0.6-GHz and 1.2-GHz channels, with a roughly proportional effect on our estimate of the ice-shell thickness," the authors explain.

In any case, the team's thickness estimates are towards the thicker end of estimates from other research. But the more damning result might concern the pores or cracks in the ice.

"Because of their low volume fraction, shallow depth relative to the depth of the ocean and small size, the pores, voids or fractures implied by our results would probably not, on their own, be a route to supply nutrients to the ocean or to provide ocean-to-surface communication," the authors write.

“How thick the ice shell is and the existence of cracks or pores within the ice shell are part of the complex puzzle for understanding Europa’s potential habitability,” said study co-author Scott Bolton, Juno's Principal Investigator from SwRI. “They provide critical context for NASA’s Europa Clipper and the ESA (European Space Agency) Juice (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) spacecraft — both of which are on their way to the Jovian system.”

The two spacecraft will give scientists the measurements they need to advance their study of the icy moon. The Europa Clipper carries an ice-penetrating radar that will measure the boundary between the ocean and the ice and map it more rigorously. The Clipper will complete almost 50 close flybys of Europa and will create a near-global map of its ice. JUICE also carries an ice-penetrating radar, though it's studying multiple moons and is not aimed solely at Europa. It will perform only a couple of Europa flybys.

The Europa Clipper will arrive first, in 2030, and Juice will arrive the year after. Once science observations start pouring in and papers are published, we'll have some long-awaited answers about Europa and its tantalizing prospect of habitability.

Universe Today

Universe Today