Nature sends us its signals in the form of light. Astrophysical phenomena emit light in all its forms, from harmless radio waves to deadly gamma-rays, and its up to us to build the facilities that can sense and dissect this light, and to understand the phenomena behind it all.

While stars can shine for billions of years, giving astronomers plenty of time to study them, other astrophysical phenomena are transient. Supernovae can light up the sky for months, outshining their host galaxies. Gamma-ray bursts (GRB), which come from supernovae and merging neutron stars, are the brightest of all cosmic light shows, but typically last only milliseconds.

But another type of rare, bright, transient light also exists to challenge and puzzle astrophysicists. They're called Luminous Fast Blue Optical Transients, and they're flashes of blue and UV light. A little more than one dozen of them have been detected, and their cause is up for debate. The two main contenders are supernovae and black holes absorbing gas and giving off bursts of light.

New research submitted to The Astrophysical Journal has an explanation for LFBOTs. It's titled "The Most Luminous Known Fast Blue Optical Transient AT 2024wpp: Unprecedented Evolution and Properties in the Ultraviolet to the Near-Infrared," and the first author is Natalie LeBaron, a graduate student at UC Berkeley. The paper is currently available at arxiv.org.

"It’s definitely not just an exploding star." - Natalie LeBaron, UC Berkeley.

Stars can die in many ways, and sorting out the signals they send in their death throes is a critical part of astrophysics. Main sequence stars like our Sun are stable for billions of years until they gradually swell and cool down to become red giants. But since their light signal changes so slowly, it's relatively easy for astrophysicists to observe many of these stars in their different stages and piece their story together. But the nature of transient phenomenon like LFBOTs is much more difficult to figure out.

The brightest of the LFBOTs was discovered last year and is named AT 2024wpp. Like its brethren, it began as a brief yet bright flash of blue light that gradually faded away, leaving faint x-ray and radio emissions in its wake. There are different potential explanations for them.

They could be caused by a compact object like a neutron star being created and somehow energized. A failed supernova could collapse directly into a black hole, which then rapidly accretes material and forms jets. They could be rapidly spinning magnetars that inject massive amounts of energy into their surroundings as they spin down.

Some astrophysicists have suggested that LFBOTs are tidal disruption events of some type, though their light doesn't match that of known TDEs. Since AT 2024wpp is easily the brightest of its type, it gives scientists the best chance to probe that light and uncover its source.

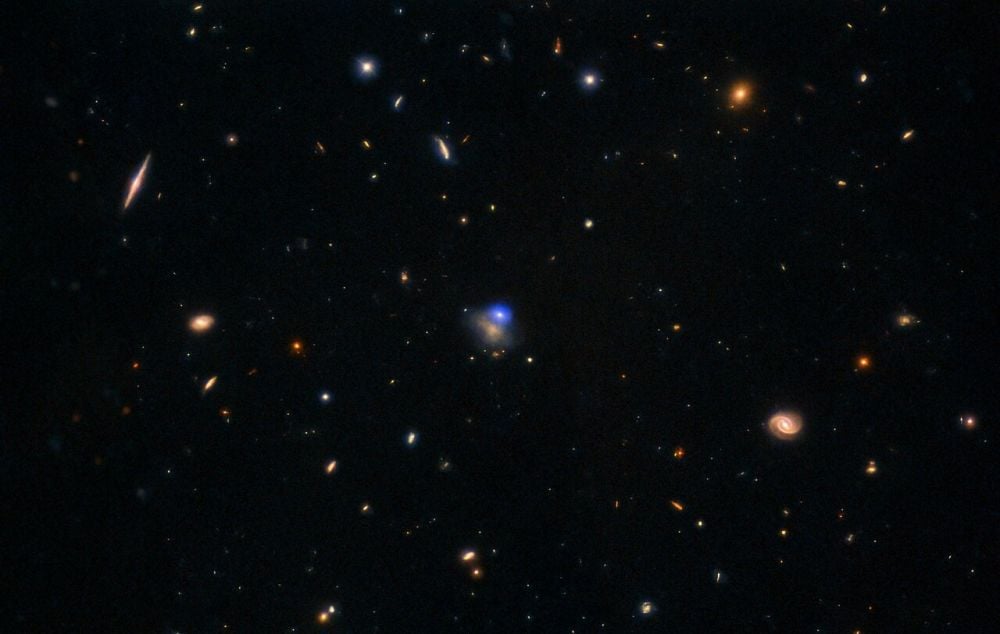

AT 2024wpp is the brightest LFBOT ever detected, ten times brighter than the next brightest one. Its extreme luminosity makes it a great target for observation and study. Image Credit: International Gemini Observatory/CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA/NASA/ESA/Hubble/Swift/CXC/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

AT 2024wpp is the brightest LFBOT ever detected, ten times brighter than the next brightest one. Its extreme luminosity makes it a great target for observation and study. Image Credit: International Gemini Observatory/CTIO/NOIRLab/DOE/NSF/AURA/NASA/ESA/Hubble/Swift/CXC/ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)

"We present an extensive photometric and spectroscopic ultraviolet-optical-infrared campaign on the luminous fast blue optical transient (LFBOT) AT 2024wpp over the first ~100 d," the authors write. The prototypical LFBOT is AT 2018 cow, and AT 2024wpp is between 5-10 times brighter. "This extreme luminosity enabled the acquisition of the most detailed LFBOT UV light curve thus far." the authors explain.

The brightness effectively rules out a supernova as the cause. Nickel-56 plays a critical role in the light emitted from supernovae. It's produced at extremely high temperatures and emits gamma-rays as it decays. Its radioactive decay powers the typical light curves from many supernovae.

"In the first ∼ 45 d, AT 2024wpp radiated > 1051 erg, surpassing AT 2018cow by an order of magnitude and requiring a power source beyond the radioactive 56Ni decay of traditional supernovae," the researchers explain. AT 2024wpp's extreme brightness also rules out a supernova as the source. The authors calculated that it's 100 times brighter than a supernova.

LFBOTs have puzzled astrophysicists for more than a decade, but AT 2024wpp and its extreme brightness may have helped them solve it. It's given them an opportunity to observe it for longer and in more detail than other LFBOTs. Multiple telescopes and observatories have observed it in different wavelengths over time. "Despite being more distant (411 Mpc) than the closest known LFBOT AT 2018cow (60 Mpc), the extreme luminosity of AT 2024wpp ultimately enabled this well-sampled dataset..." the authors write.

*This figure from the research illustrates the different observatories that observed AT 2024wpp and the data that they collected they collected in different wavelengths. Image Credit: LeBaron et al. 2025. ApJ*

*This figure from the research illustrates the different observatories that observed AT 2024wpp and the data that they collected they collected in different wavelengths. Image Credit: LeBaron et al. 2025. ApJ*

“The sheer amount of radiated energy from these bursts is so large that you can't power them with a core collapse stellar explosion — or any other type of normal stellar explosion,” says Natalie LeBaron, UC Berkeley graduate student and first author on the paper presenting the Gemini data [1]. “The main message from AT 2024wpp is that the model that we started off with is wrong. It’s definitely not just an exploding star.”

The researchers concluded that AT 2024wpp is a tidal disruption event (TDE). But not an average one.

TDEs are when a black hole's powerful tidal force "spaghettifies" a star that got too close. Some of the material stripped from the star gathers in an accretion disk around the BH. The material heats up, then emits radiation that our telescopes and observatories can detect.

In this case, the tidal disruption was extreme, as a black hole with 100 solar masses completely shredded its stellar companion. The pair were in a binary pair, and for a long time, the black hole drew gas from its companion. The gas gathered in a cloud around the black hole, but too far away to be pulled across the BH's event horizon.

Over time, the companion star was drawn closer and closer to the BH. Eventually, its fate was sealed and it was torn apart. Matter from the star joined the accretion disk, slamming into the existing material. The resulting shocks and heat generated x-rays, UV light, and blue light. But all of the gas didn't end up in the accretion disk. Some was drawn toward the BHs poles, where it was emitted in powerful jets. When that material in the jets struck the surrounding interstellar medium, it generated radio emissions.

*This infographic depicts AT 2024wpp, the brightest fast blue optical transient (FBOT) ever seen, and the likely mechanism behind its extreme power output. Image Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Margutti/P. Marenfeld*

*This infographic depicts AT 2024wpp, the brightest fast blue optical transient (FBOT) ever seen, and the likely mechanism behind its extreme power output. Image Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Margutti/P. Marenfeld*

The companion star may have been a highly-evolved Wolf-Rayet star, which have already used most of their supply of hydrogen. This lines up with the observations that show only weak hydrogen emissions.

The only way to understand LFBOTs better is to find more of them, and to study them in greater detail. That should happen in the near future. A pair of ultraviolet missions—UVEX and ULTRASAT—are planned in the next few years. "Tens of LFBOTs per year will be discovered by these surveys," the authors write.

Astrophysicists are only beginning to understand the nature of these objects in detail. A dedicated effort to detect more of them and to observe them in greater deal will drive progress. Comprehensive datasets are key to understanding them.

"We conclude by emphasizing that only two LFBOTs (three if including AT 2024puz) to date have extensive multiwavelength datasets; thus, future observations are required to probe the diversity of this class and put meaningful population-level constraints on the intrinsic nature of these intriguing objects," the author write.

Universe Today

Universe Today