Almost every massive galaxy is has a supermassive black hole at its core, an object containing millions or even billions of times the mass of our Sun. Most of these giants simply lurk in the darkness, quietly consuming material from their surroundings while emitting barely a hint of radiation. But a small fraction shine brilliantly, pumping out enormous amounts of energy as active galactic nuclei (AGN). For decades, astronomers have debated what triggers this dramatic awakening. Now, a new dataset from the Euclid space telescope provides evidence that violent collisions between galaxies are the primary culprit.

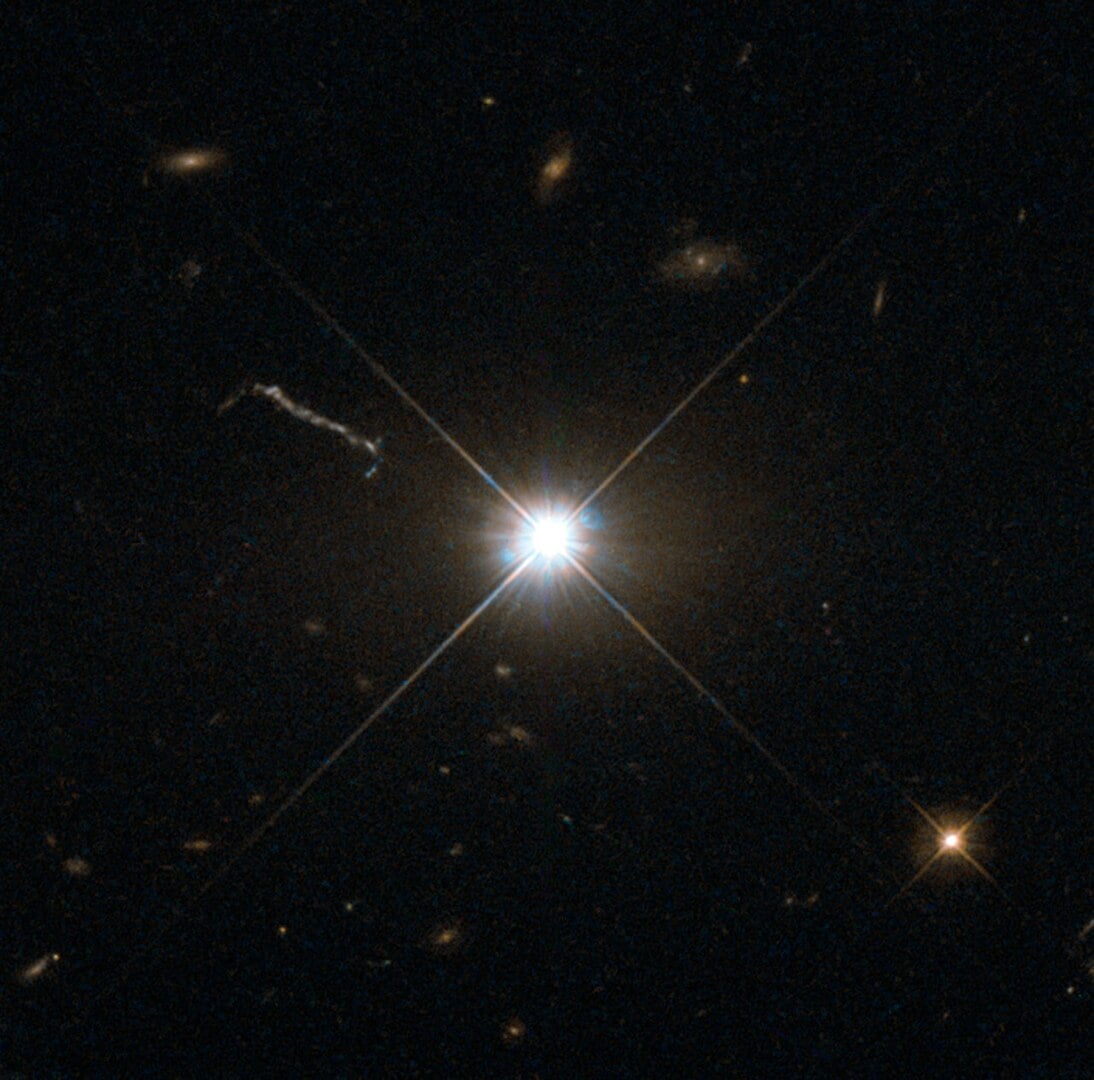

Quasar 3C 273 observed by the Hubble Space Telescope. The relativistic jet of 3C 273 appears to the left of the bright quasar, and the four straight lines pointing outward from the central source are diffraction spikes caused by the telescope optics (Credit : NASA/ESA)

Quasar 3C 273 observed by the Hubble Space Telescope. The relativistic jet of 3C 273 appears to the left of the bright quasar, and the four straight lines pointing outward from the central source are diffraction spikes caused by the telescope optics (Credit : NASA/ESA)

When two galaxies merge, the collision creates gravitational chaos that throws gas, dust and stars across vast distances. This turbulence should drive extra material toward each galaxy's central black hole, piling it up in the accretion disk where friction and compression heat it to incredible temperatures. The result would be an AGN bright enough to outshine its entire host galaxy.

Testing this idea has proved difficult though with previous studies relying on limited sample sizes and image quality insufficient to reliably identify both mergers and faint AGN. Then Euclid arrived. Within just one week of operations, the telescope captured high quality images covering an area that took the Hubble Space Telescope more than three decades to observe.

To make use of this wealth of data, researchers at SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research developed an AI-powered image decomposition tool. This new approach can identify AGN that other methods miss entirely, while also measuring their energy output with incredible precision. Applied to a million galaxies, dozens of times larger than any previous study, the results proved decisive.

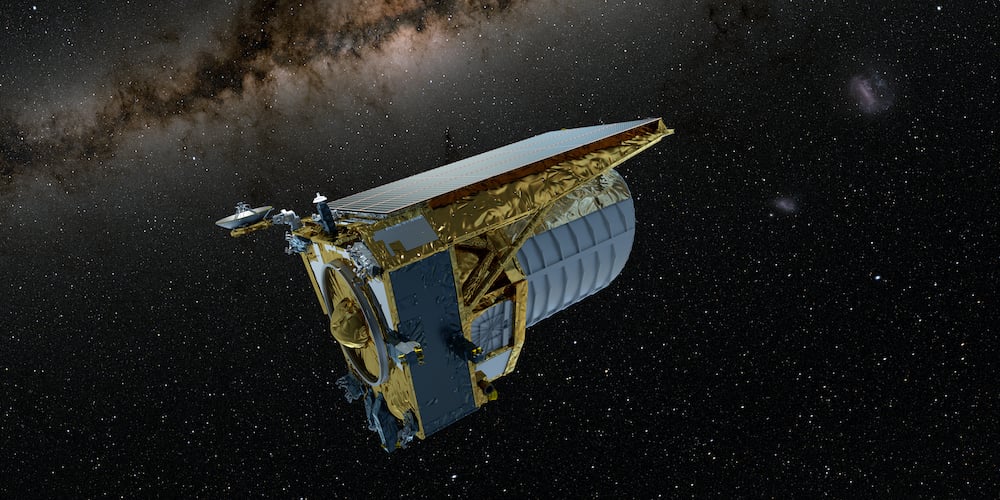

Artist impression of the Euclid mission in space (Credit : ESA)

Artist impression of the Euclid mission in space (Credit : ESA)

The team found that merging galaxies contain significantly more AGN than their isolated counterparts. The exact ratio depends on the merger's stage. In dynamically young, dust rich mergers where the AGN remains visible only in infrared wavelengths, there are six times more active black holes. In mergers approaching completion, where the dust has settled and X-rays can escape, the ratio drops to two times higher, though this might reflect that some apparently isolated galaxies are actually post merger systems that have settled into a regular appearance.

Most strikingly, the most luminous AGN are found almost exclusively in merging systems. This suggests that while other mechanisms might trigger moderate black hole activity, galaxy collisions are essential, perhaps the only way, to fuel the universe's most extreme objects.

The study revealed that, as galaxies merge throughout the history of the universe, their central black holes don't just grow larger, they briefly blaze into life, reshaping their surroundings with powerful radiation and outflows that can halt star formation across the entire merged system.

Source : Euclid dataset of a million galaxies proves connection between galaxy mergers and AGN

Universe Today

Universe Today