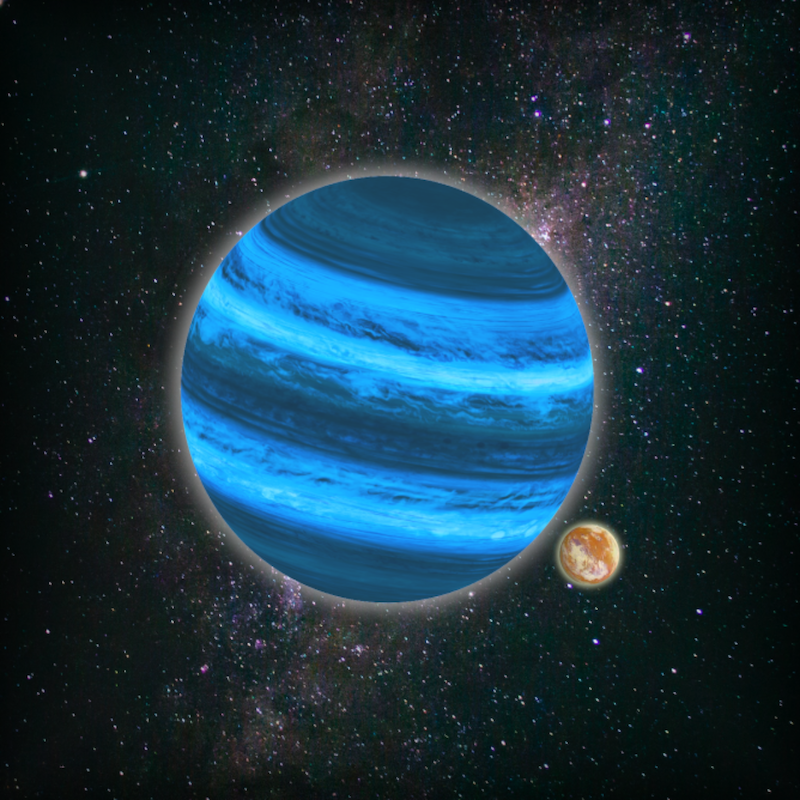

Free-Floating Planets, or as they are more commonly known, Rogue Planets, wander interstellar space completely alone. Saying there might be a lot of them is a bit of an understatement. Recent estimates put the number of Rogue Planets at something equivalent to the number of stars in our galaxy. Some of them, undoubtedly, are accompanied by moons - and some of those might even be the size of Earth. A new paper, accepted for publication into the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and also available in pre-print on arXiv, by David Dahlbüdding of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich and his co-authors, describes how some of those rogue exo-moons might even have liquid water on their surfaces.

That probably sounds completely counter-intuitive. Liquid water can only exist when the environment is warm enough, and that warmth primarily comes from a host planet’s star. So how could a rogue planet’s moon, which, by definition, does not have a star near it, have liquid water on its surface? The simple answer is - tides.

There’s some nuance to that, obviously, but tidal heating is certainly capable of producing liquid water on a moon. It's the same force that powers sub-surface oceans on Enceladus and Europa, and even causes molten rock volcanoes on Io, without any direct input of energy from the Sun. Being pushed and pulled by their respective gas giant planets is enough to heat up the interiors of these moons enough to melt water.

Fraser discusses the possibility of nearby rogue planets.But nowhere in our solar system is there liquid water on the surface of any of these moons. Enceladus and Europa have massive ice sheets covering their liquid water oceans, which protects heat generated in the moon's core, allowing the temperature at those depths to hit the melting point of water. So how would rogue exomoons manage to hold onto their liquid surface water without the benefit of an ice sheet holding the heat in place?

Original thinking in this area, culminating in a paper by Guilia Roccetti also of Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, focused on whether having an atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide could effectively trap the energy from the tidal heating on the surface without the need for an ice sheet. To form enough of a protective barrier, the pressure of the CO2 had to be notably high. However, with high pressure and relatively low heat from the tidal forces, the CO2 condensed into liquid or ice form, causing the atmosphere to collapse and the moon itself to freeze.

But there’s an alternative gas that doesn’t seem to suffer the same fate - hydrogen. It doesn’t turn into a liquid except at absurdly low temperatures, so it won’t collapse out of the atmosphere. However, in usual circumstances, it’s transparent to infrared energy, meaning the heat from the tidal forces could just radiate away. But at very high pressures, H2 molecules collide to form momentary dipoles, and, in a process known as Collision-Induced Absorption (CIA), absorb infrared light. This effectively causes the hydrogen atmosphere to act like a giant greenhouse blanket, allowing the surface of the moon to stay warm enough for liquid water to exist with just the tidal heating from its host planet.

Anton Petrov has several videos on how moons around rogue planets could host life - here’s one of them. Credit - Anton Petrov YouTube ChannelTo prove their point, the researchers ran a series of simulations of the temperature of moons with different compositions and pressures of atmospheres, as well as the impact different levels of tidal heating had on the potential for liquid water. They used both a radiative heat transfer model as well as an equilibrium chemistry model to ensure they were accurately reflecting real atmospheres that could exist on these rogue moons. And what they found was quite startling.

At Earth-standard pressures of 1 bar, liquid water could exist on the surface of these moons for up to 95 million years. Perhaps more impressively, with an atmosphere that was 100 times thicker than that of Earth, liquid water could exist on a moon for 4.3 billion years - roughly the age of the Earth itself. How likely it is that a rogue exomoon has that strong of an atmosphere remains to be seen, but with the sheer number of them out there, it’s certainly possible that at least one does.

On any moon with liquid water on its surface, there’s an interesting nuance to one particular life-giving chemical - RNA. The moon’s orbit is likely highly elliptical around its parent planet, which causes massive, global tides of any liquid water on its surface - like a reverse effect of how the tides on Earth are affected by the Moon’s gravity. This creates a “wet/dry” cycle that allows RNA to form. On early Earth, scientists think this process may have happened in tidal pools that changed with the planet’s tides. Needless to say, the tides on any such exomoon would be much, much bigger.

So there is, in fact, the possibility that life could develop on a moon the size of our planet orbiting a massive planet, but not orbiting any star. Given that there are likely hundreds of billions of them in our galaxy alone, that could lead to some very interesting and alien biology. But for now, this is all just speculation as we haven’t even directly detected a rogue exomoon yet. Physics says they’re out there, though, and with even increasing observational capabilities, its only a matter of time before we find one. Maybe, when we do, it will be worth searching it for biosignatures - one can dare to dream anyway.

Learn More:

D. Dahlbüdding et al. - Habitability of Tidally Heated H-Dominated Exomoons around Free-Floating Planets

UT - Never Mind Rogue Planets. Their Rogue Moons Could Support Life

Universe Today

Universe Today