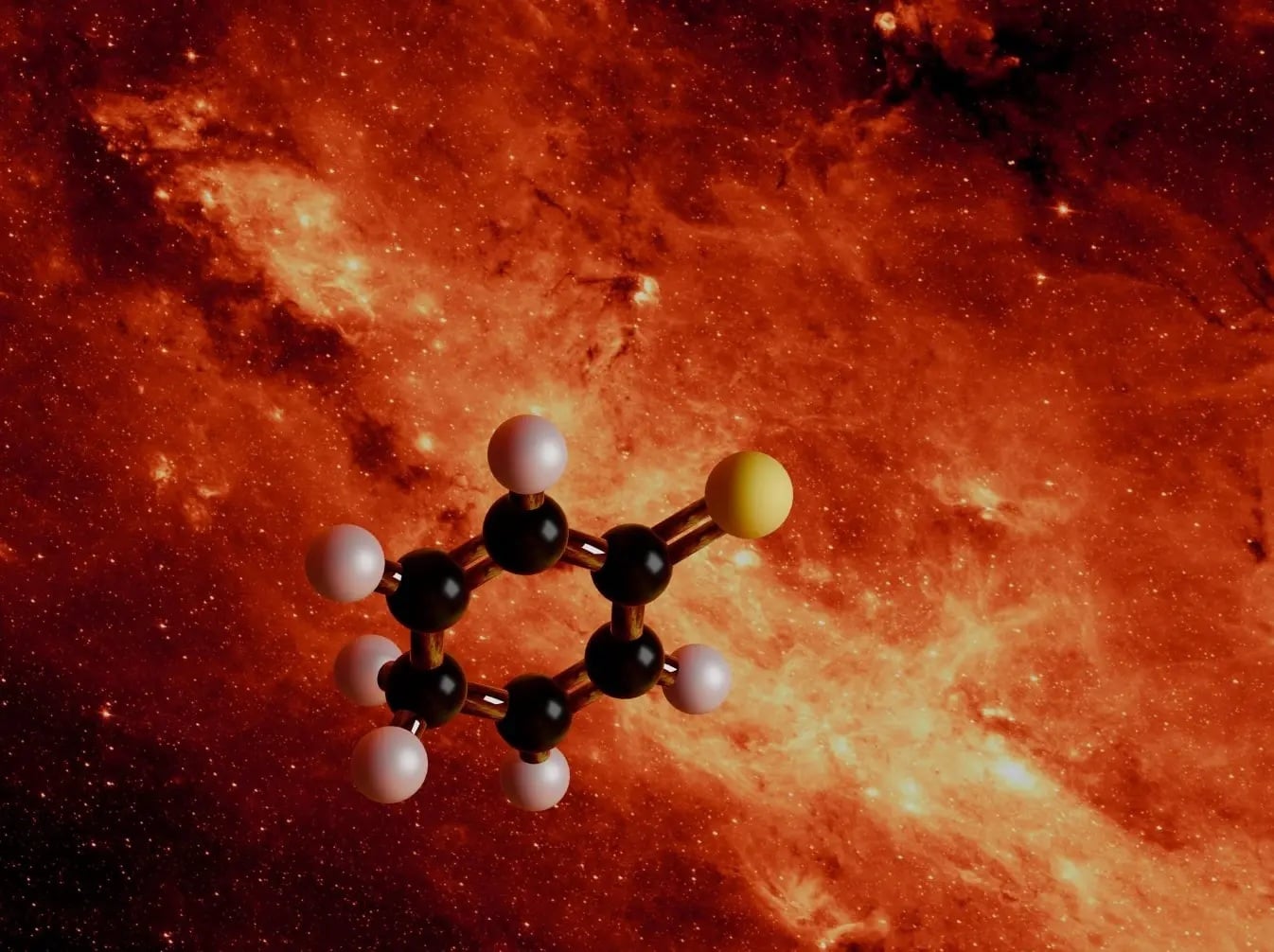

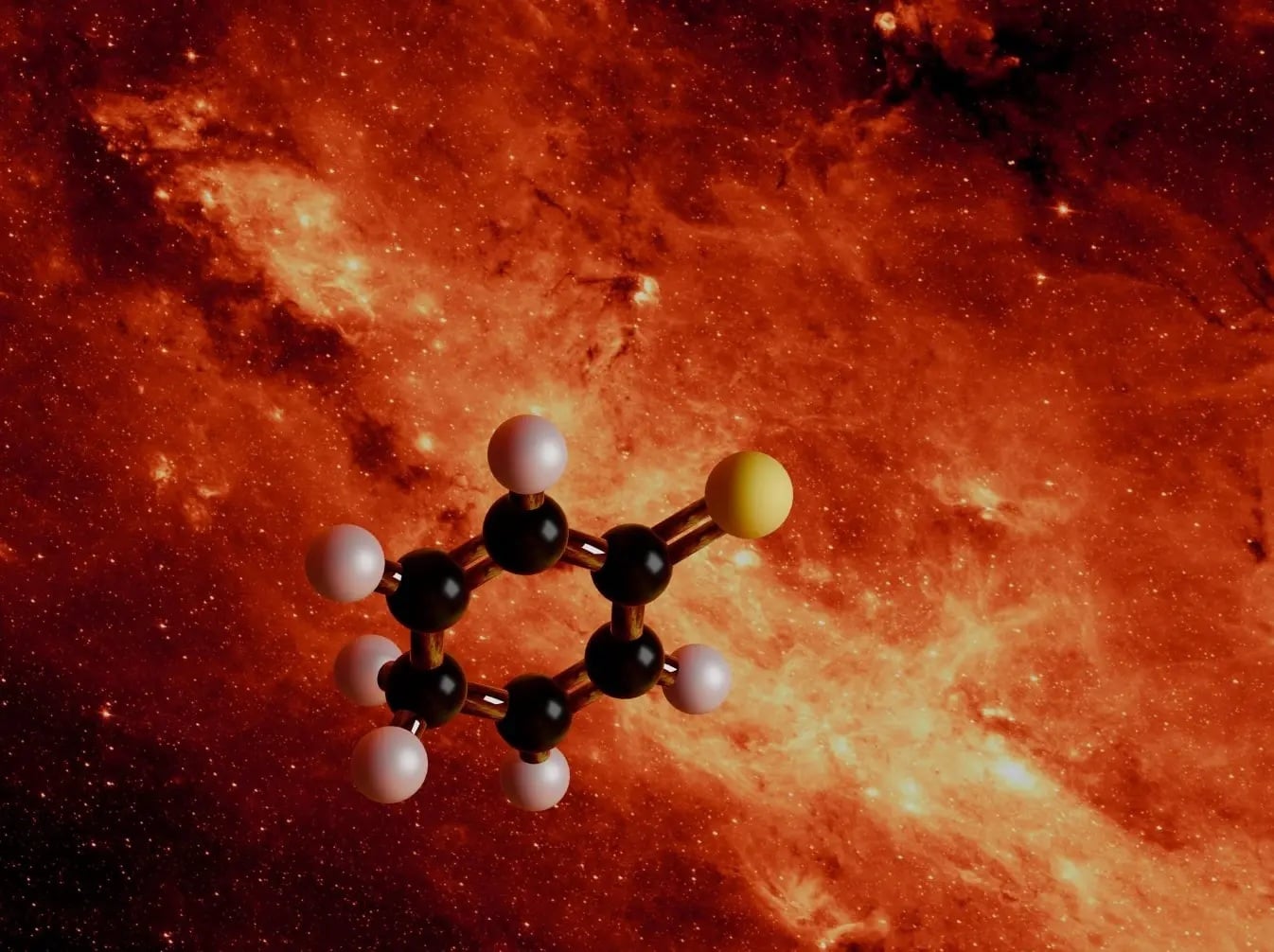

For the first time, a complex, ring-shaped molecule containing 13 atoms—including sulfur—has been detected in interstellar space, based on laboratory measurements. The discovery closes a critical gap by linking simple chemistry in space with the complex organic building blocks found in comets and meteorites. This represents a major step toward explaining the cosmic origins of the chemistry of life.

Continue reading

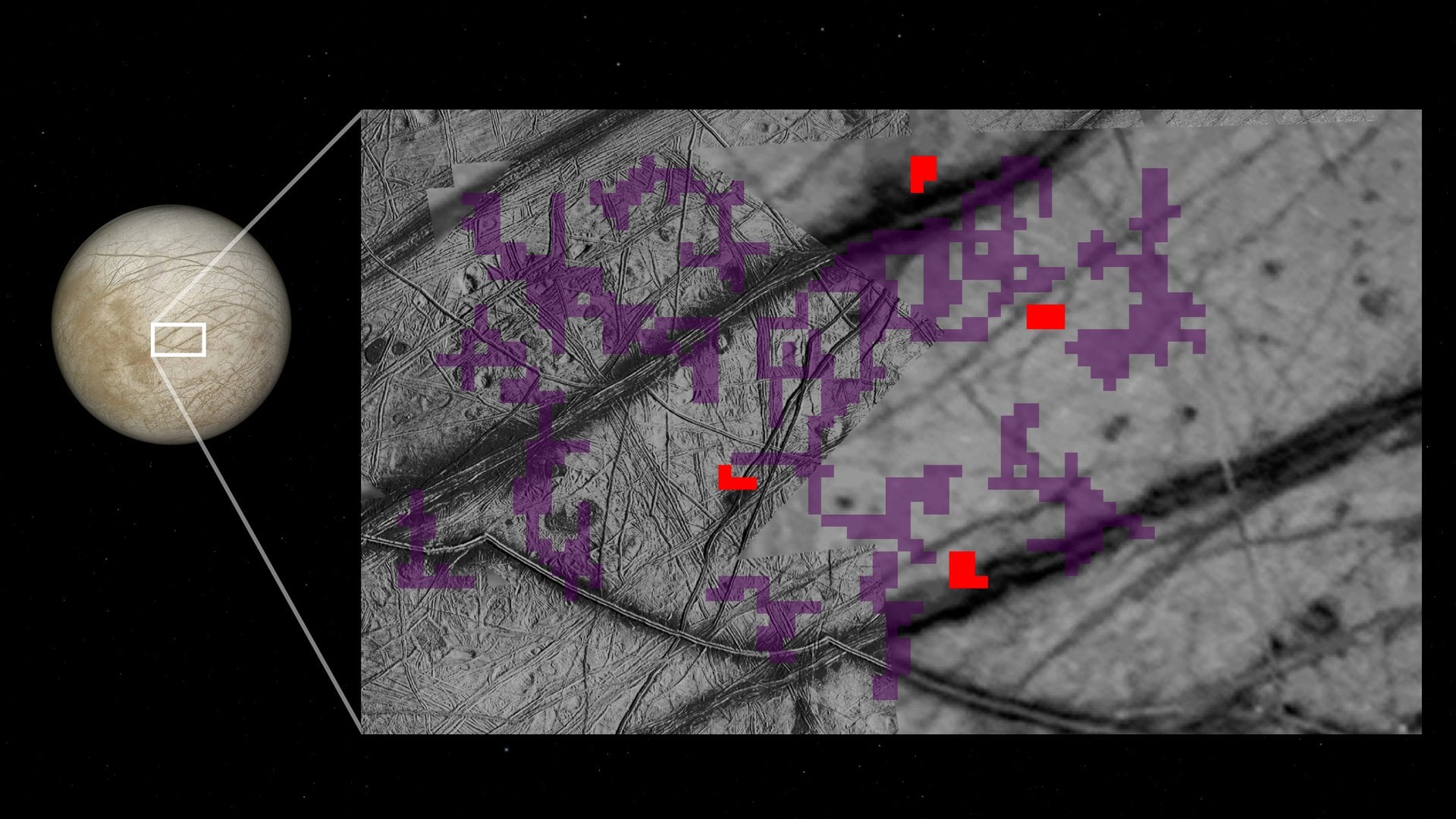

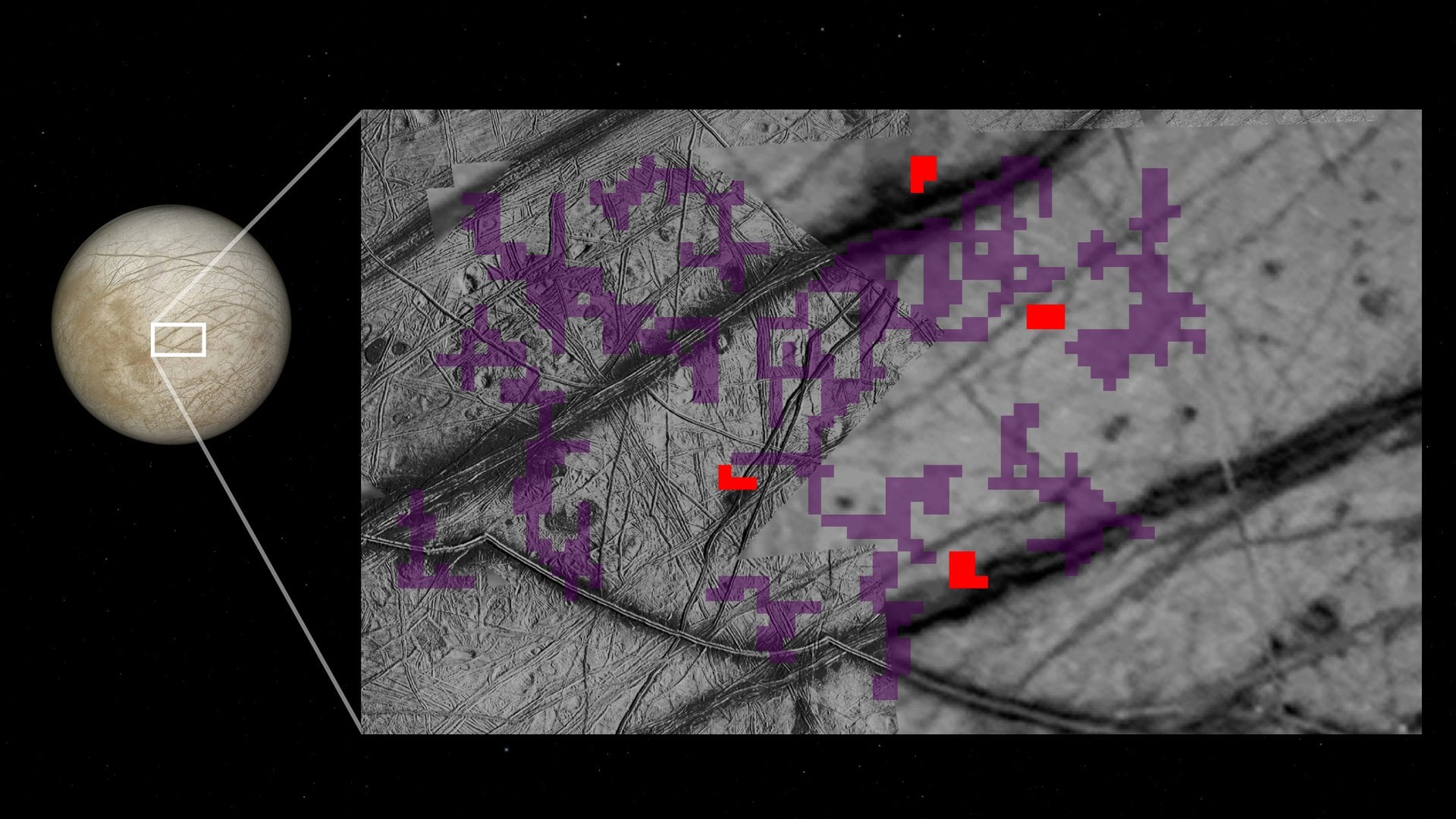

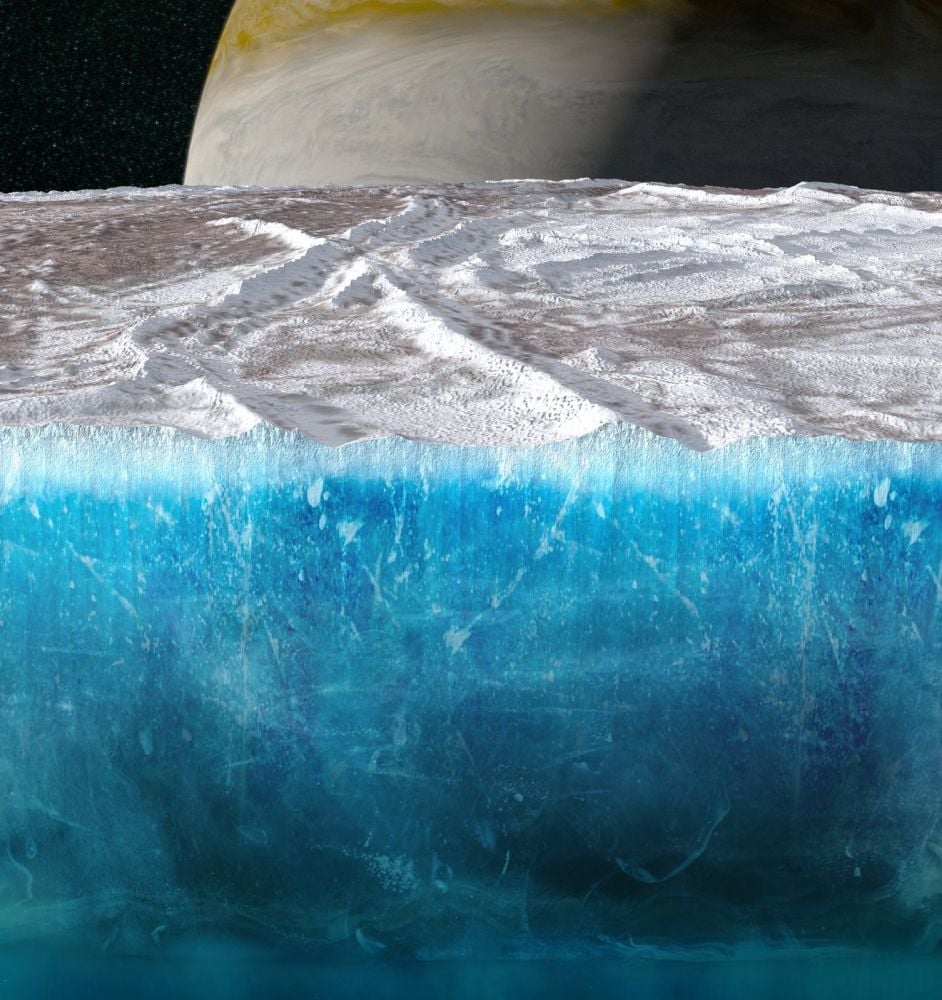

The search for life-supporting worlds in the Solar System includes the Jovian moon Europa. Yes, it's an iceberg of a world, but underneath its frozen exterior lies a deep, salty ocean and a nickel-iron core. It's heated by tidal flexing, and that puts pressure on the interior ocean, sending water and salts to the surface. As things turn out, there's also evidence of ammonia-bearing compounds on the surface. All these things combine to provide a fascinating look at Europa's geology and potential as a haven for life.

Continue reading

Red Geysers are an unusual class of galaxy that contain only old stars. Despite having plenty of star-forming gas, Red Geysers are quenched. Astronomers have mapped the flow of gas in these galaxies and figure out why they're dormant.

Continue reading

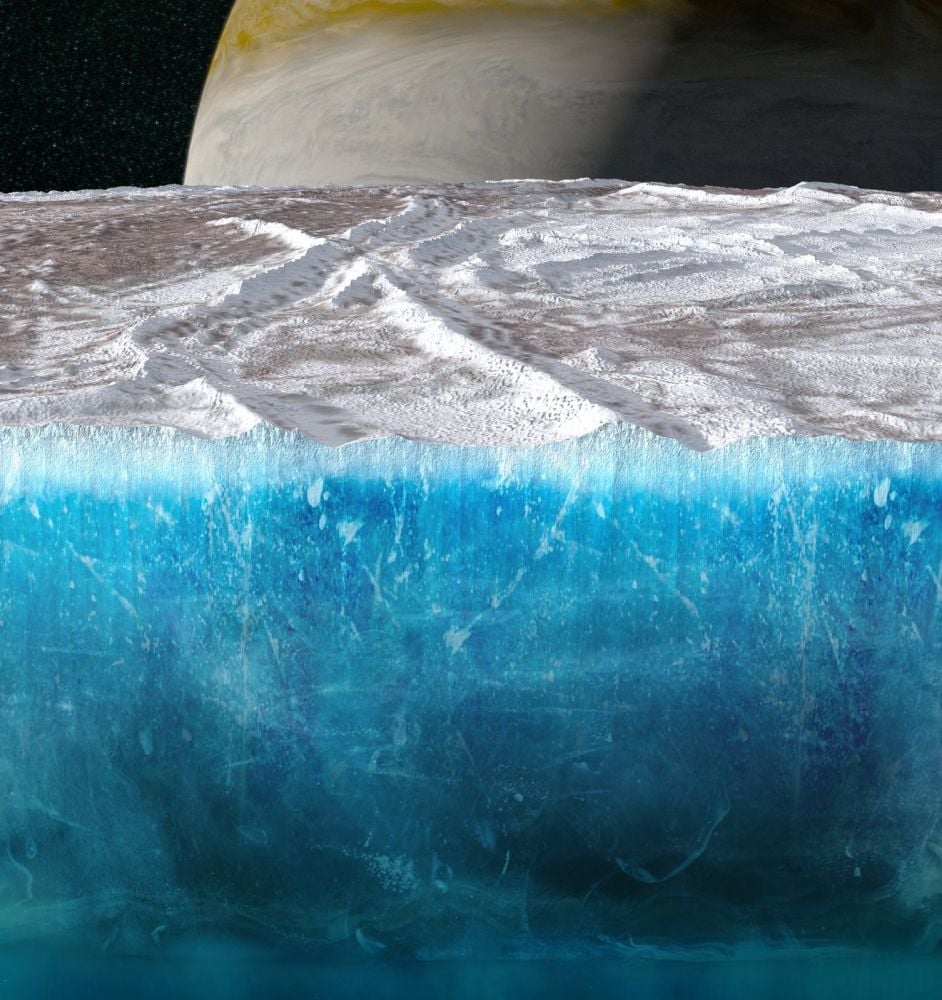

Jupiter's icy moon Europa is a tantalizing target in the search for habitability in our Solar System. Its thick, global ice sheet overlies a warm, salty, chemically-rich ocean. But for life to exist in that ocean, nutrients need to find their way from the surface to the ocean. New research says that may be very difficult.

Continue reading

The light, rare element boron, better known as the primary component of borax, a longtime household cleaner, was almost mined to exhaustion in parts of the old American West. But boron could arguably be an unsung hero in cosmic astrobiology, although it's still not listed as one of the key elements needed for the onset of life.

Continue reading

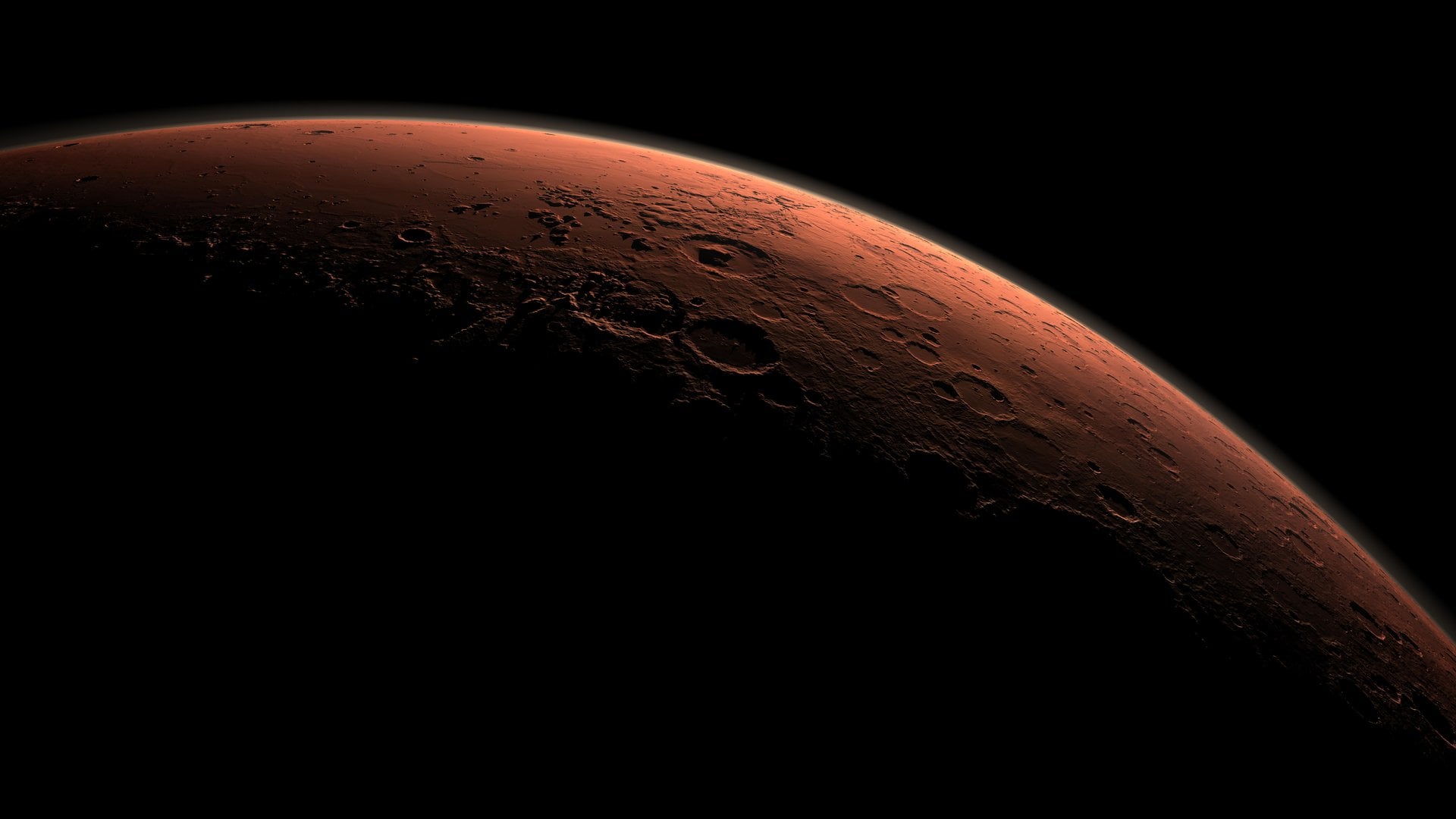

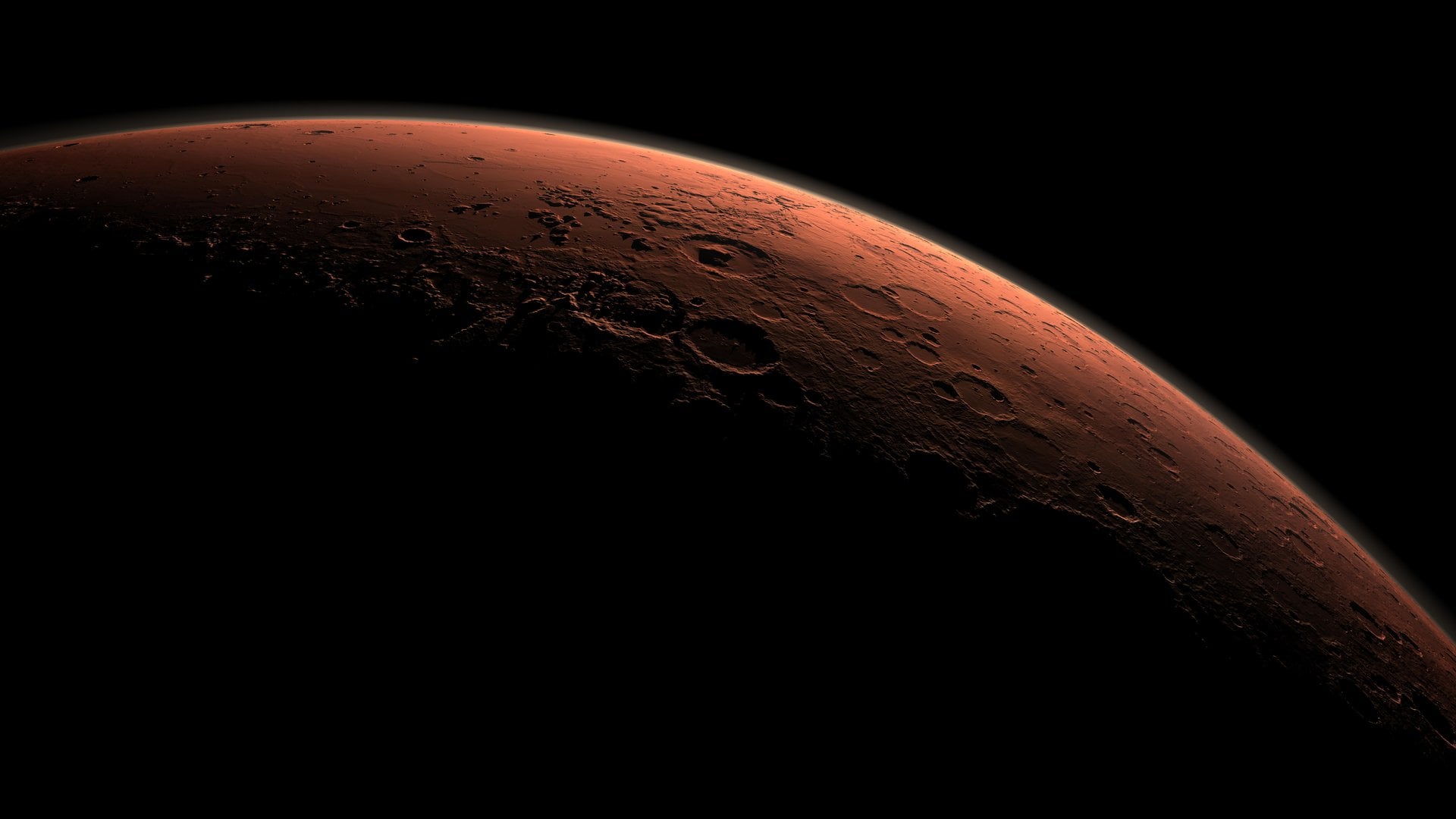

When the rover now named Perseverance landed in Jezero crater in early 2021, scientists already knew they had picked an interesting place to scope out. From space, they could see what looked like a bathtub ring around the crater, indicating there could once have been water there. But there was some debate about what exactly that meant, and it’s taken almost five years to settle it. A new paper from PhD student Alex Jones at Imperial College London and his co-authors has definitively settled the debate on the source of that feature - part of it was once a beach.

Continue reading

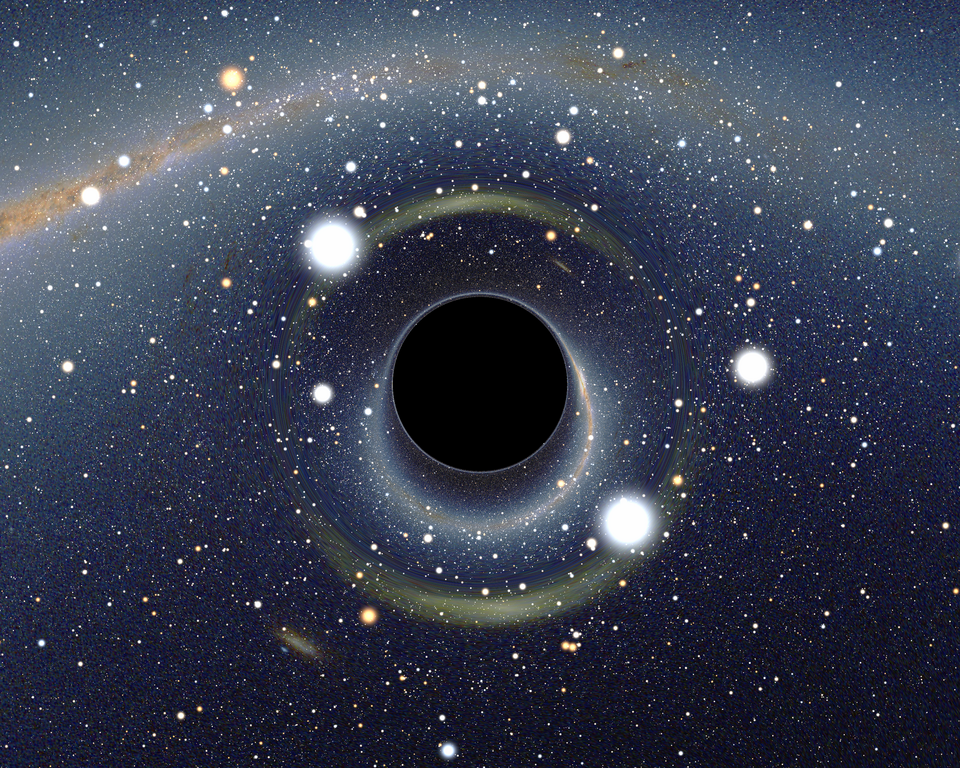

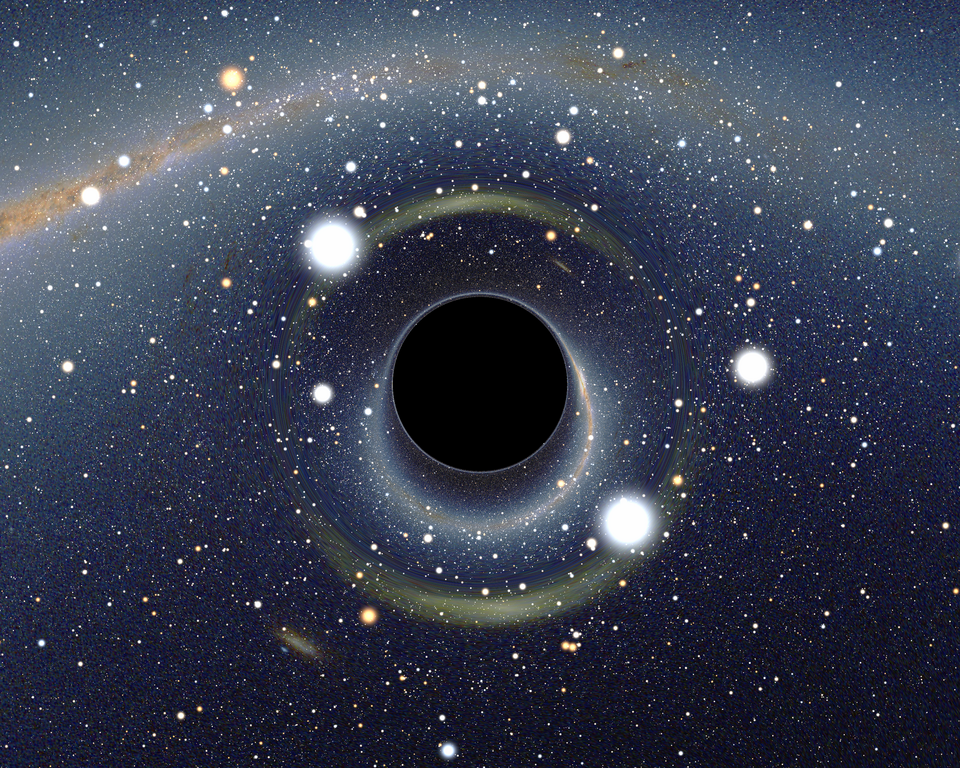

Researchers at KAIST have developed a breakthrough technology that could dramatically improve our ability to image black holes and other distant objects. The team created an ultra precise reference signal system using optical frequency comb lasers to synchronise multiple radio telescopes with unprecedented accuracy. This laser based approach solves long standing problems with phase calibration that have plagued traditional electronic methods, particularly at higher observation frequencies.

Continue reading

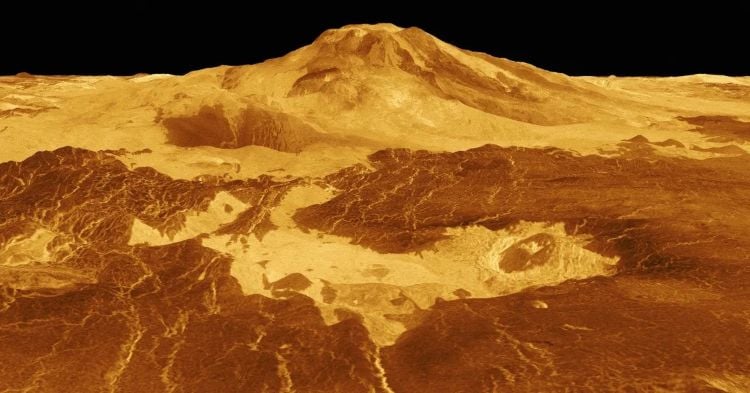

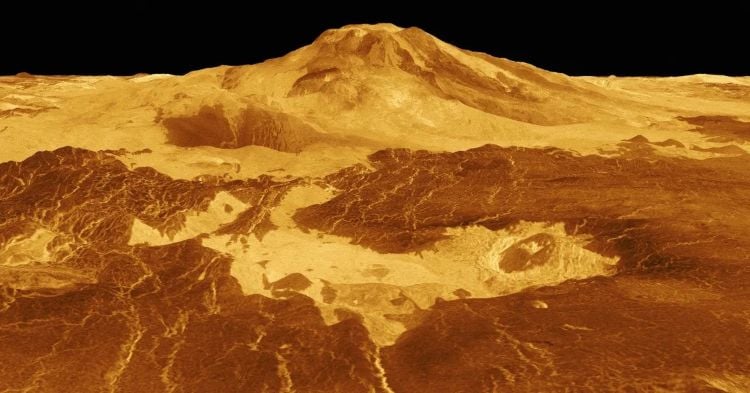

It’s 2050 and you’re living on Venus. This might come as a surprise due to the planet’s crushing surface pressures (~92 times of Earth) and searing surface temperatures (~465 degrees Celsius/870 degrees Fahrenheit), which is equivalent to ~900 meters (3,000 feet) underwater and hot enough to melt lead, respectively. But you’re not living on the surface. Instead, you’re safe and sound inside a lava tube habitat scanning data from the latest orbiter images while sipping on some habitat-made espresso.

Continue reading

Solar flares are one of the most closely watched processes in solar physics. Partly that’s because they can prove hazardous both to life and equipment around Earth, and in extreme cases even on it. But also, it’s because of how interestingly complex they are. A new paper from Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research and his co-authors, available in the latest edition of Astronomy & Astrophysics, uses data collected by ESA’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft to watch the formation process of a massive solar flare. They discovered the traditional model used to describe how solar flares form isn’t accurate, and they are better thought of as being caused by miniaturized “magnetic avalanches.”

Continue reading

A new study led by researchers from Aarhus University showed that amino acids spontaneously bond in space, producing peptides that are essential to life as we know it. Their findings suggest that the building blocks of life are far more common throughout space than previously thought, with implications for astrobiology and SETI.

Continue reading

Astronomers have solved a bit of a mystery that had them questioning whether one of the most extreme stars ever observed was about to explode. WOH G64, a massive red supergiant in the Large Magellanic Cloud, began behaving so strangely that researchers suspected it had evolved into a rare yellow hypergiant on the brink of supernova. But new observations from the Southern African Large Telescope reveal the star is still very much a red supergiant, yet still exhibiting strange behaviour.

Continue reading

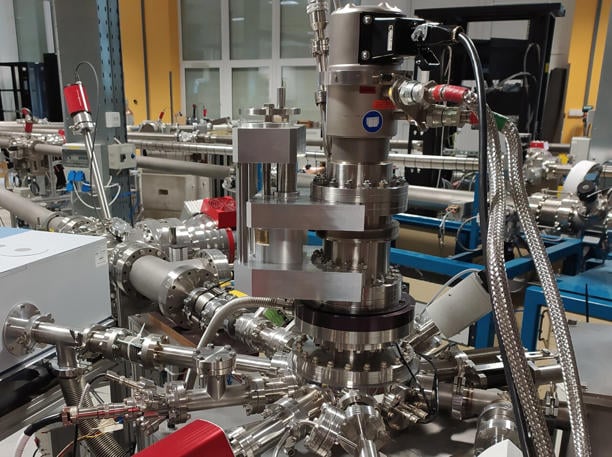

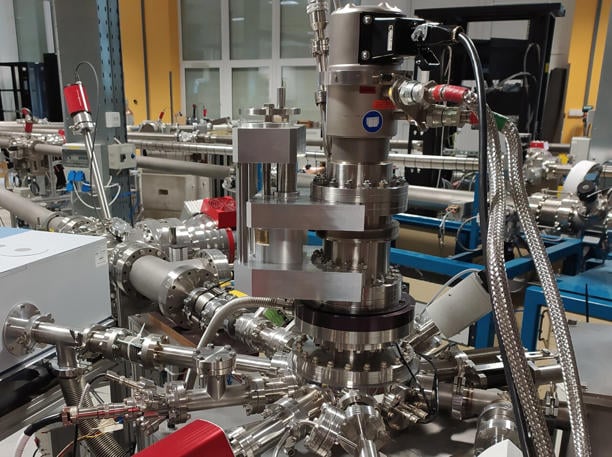

NASA has completed its first major testing of nuclear reactor hardware for spacecraft propulsion in over 50 years, marking a crucial step toward faster, more capable deep space missions. Engineers at Marshall Space Flight Center conducted more than 100 ‘cold flow’ tests on a full scale reactor engineering development unit throughout 2025, gathering vital data on how propellant flows through the system under various conditions.

Continue reading

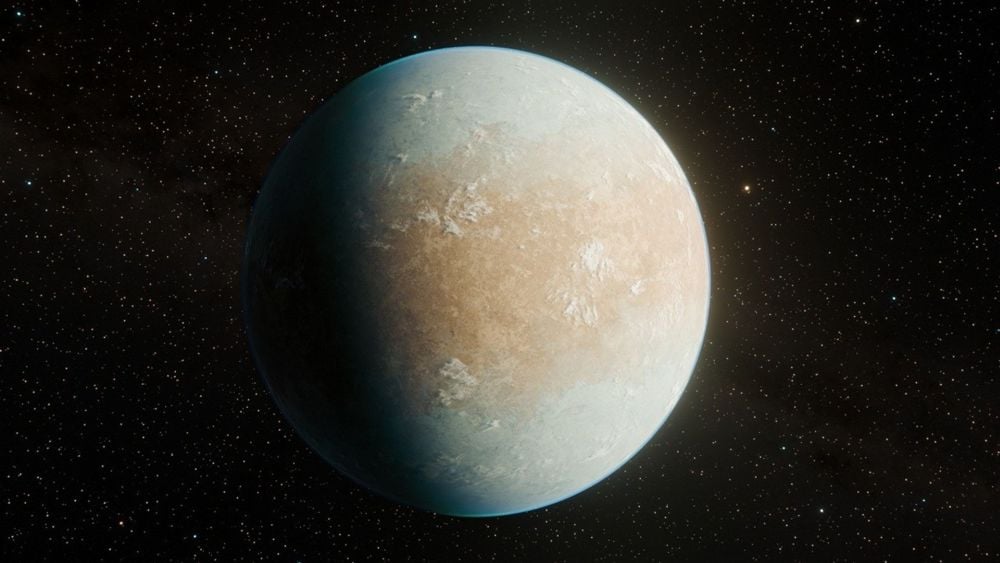

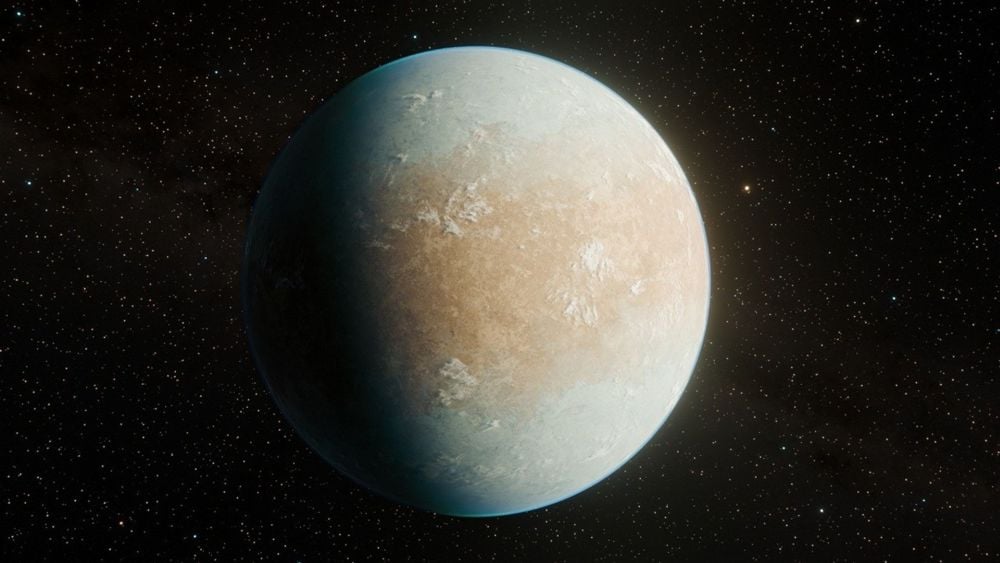

Finding Earth-like planets is the primary driver of exoplanet searches because as far as we know, they're the ones most likely to be habitable. Astronomers sifting through data from NASA's Kepler Space Telescope have found a remarkably Earth-like planet, but with one critical difference: it's as cold as Mars.

Continue reading

The Milky Way's Galactic Center and Bulge are shrouded in thick dust and tightly-packed with stars. It's a tough region to observe, but the Nancy Gracy Roman Space Telescope is built for the task. Its Galactic Bulge Time-Domain Survey will find more than 100,000 exoplanets, along with stars, black holes, neutron stars, and even rogue planets.

Continue reading

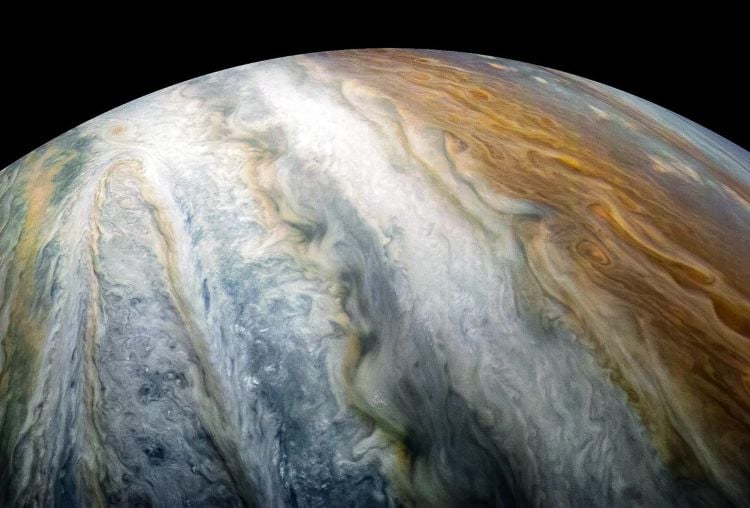

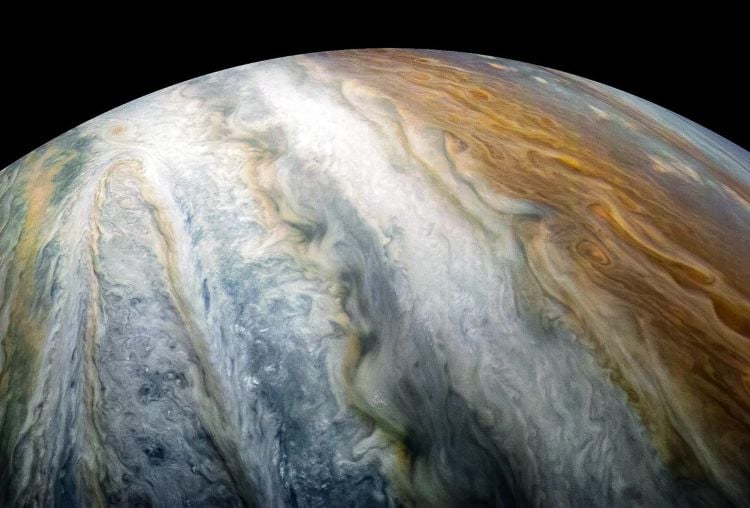

Jupiter’s atmosphere and clouds have mesmerized stargazers for centuries, as their multi-colored, swirling layers can easily be viewed from powerful telescopes on Earth. However, NASA’s Juno spacecraft has upped the ante regarding our understanding of Jupiter’s atmospheric features, having revealed them in breathtaking detail. This includes images of massive lightning storms, clouds swallowing clouds, polar vortices, and powerful jet streams. Yet, despite its beauty and wonder, scientists are still puzzled about the processes occurring deep inside Jupiter’s atmosphere that result in these incredible features.

Continue reading

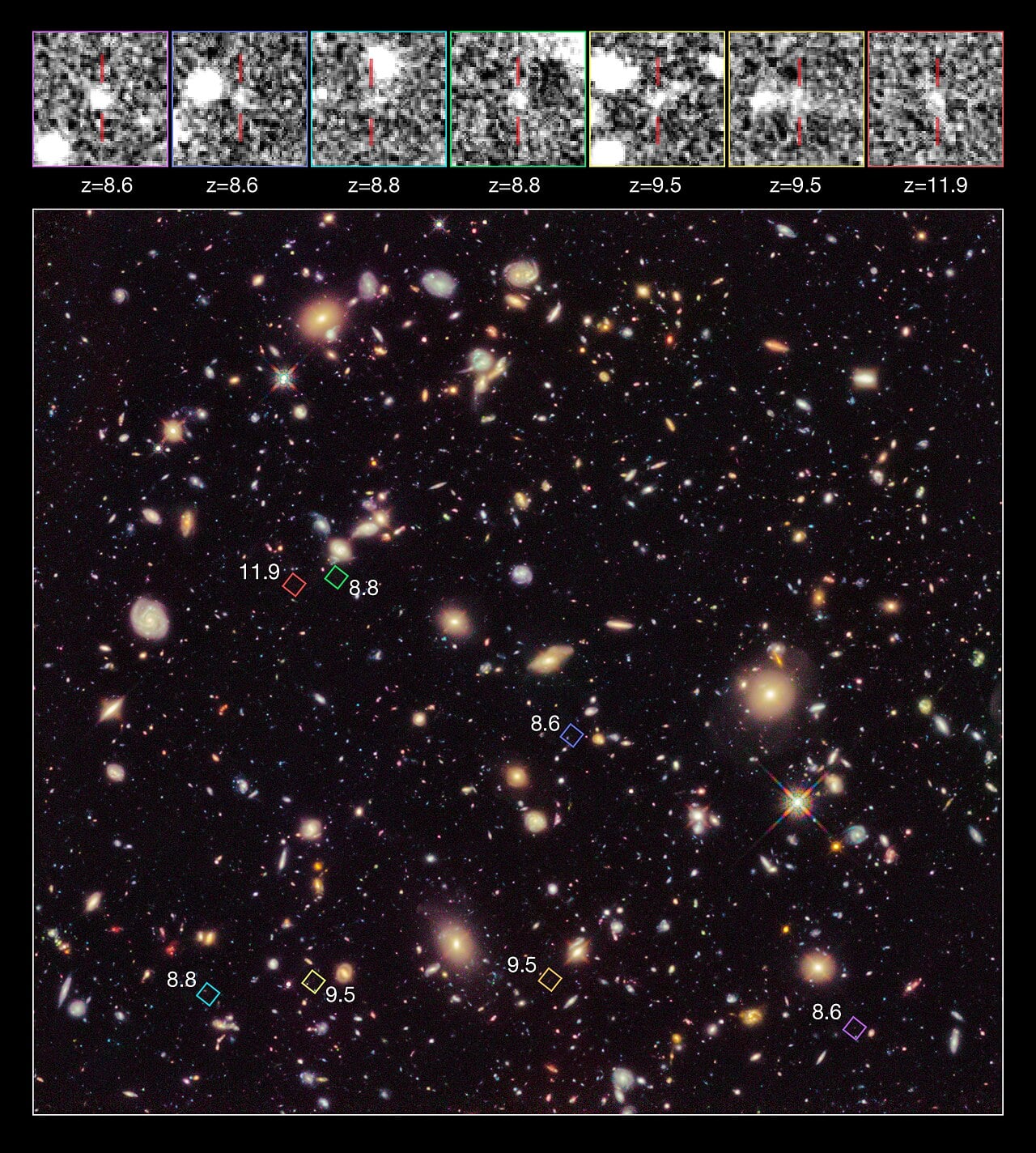

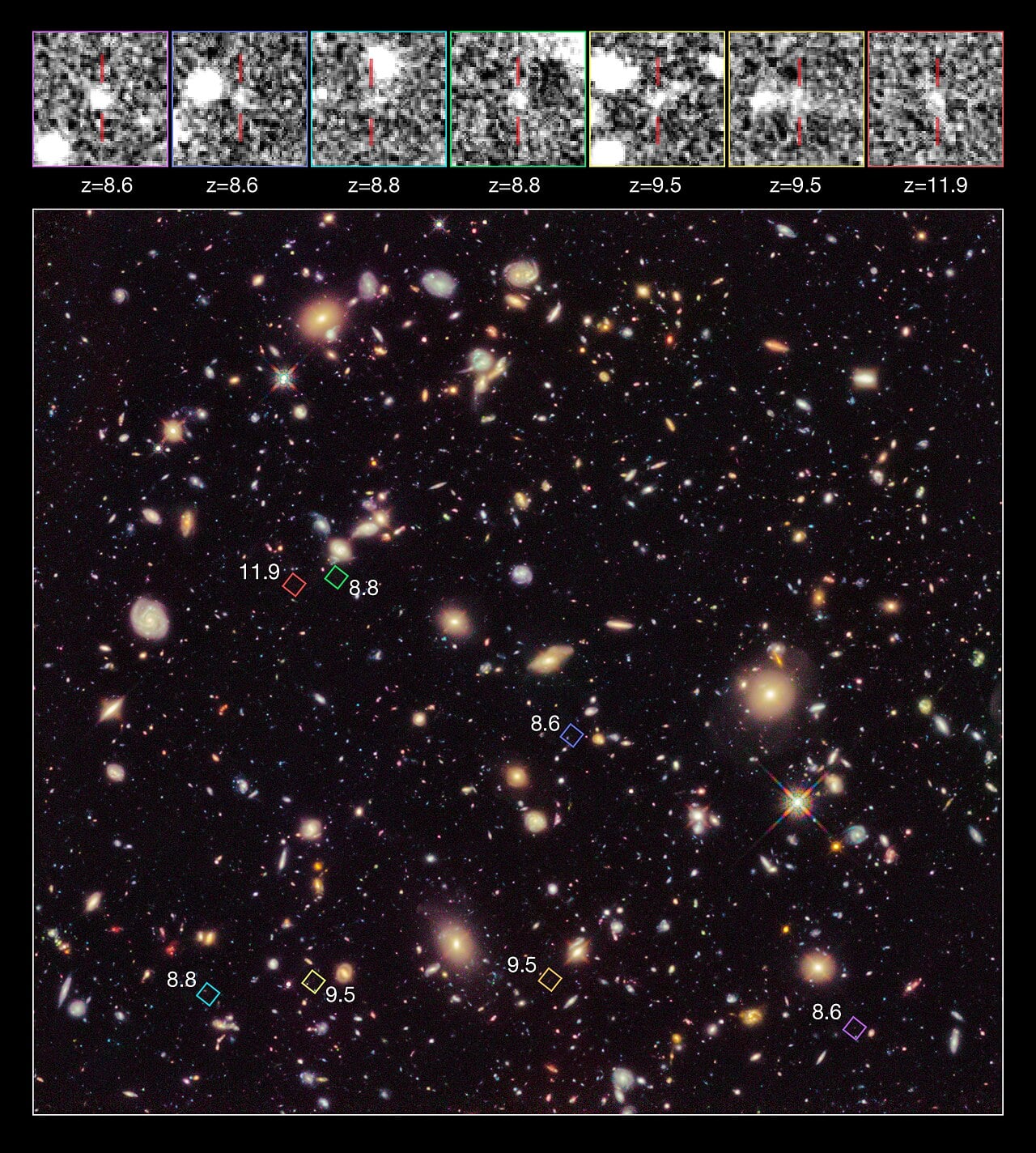

The Dark Energy Survey Collaboration collected information on hundreds of millions of galaxies across the Universe using the U.S. Department of Energy-fabricated Dark Energy Camera, mounted on the U.S. National Science Foundation Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at CTIO, a Program of NSF NOIRLab. Their completed analysis combines all six years of data for the first time and yields constraints on the Universe's expansion history that are twice as tight as past analyses.

Continue reading

After months of protests led by Nobel laureate Reinhard Genzel, the American energy company AES Andes has abandoned plans to build a massive solar and wind facility just kilometres from one of the world's premier telescope sites. The decision preserves the pristine night skies above Chile's Paranal Observatory, where the European Southern Observatory operates some of humanity's most powerful eyes on the universe.

Continue reading

Nearly a century after Edwin Hubble discovered the universe's expansion, astronomers have finally explained the nagging mystery of why most nearby galaxies rush away from us as if the Milky Way's gravity doesn't exist? The answer lies in a vast, flat sheet of dark matter stretching tens of millions of light years around us, with empty voids above and below that make the expansion appear smoother than it should.

Continue reading

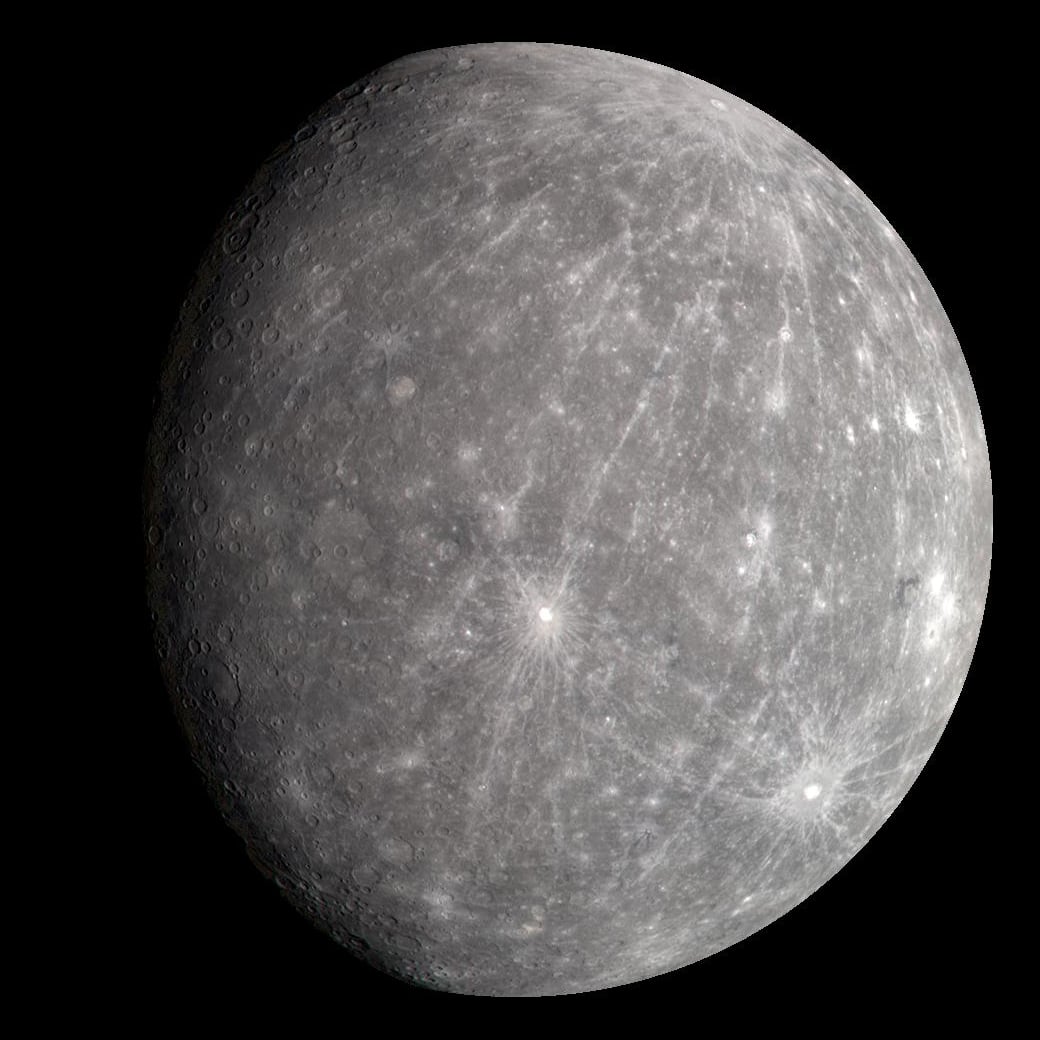

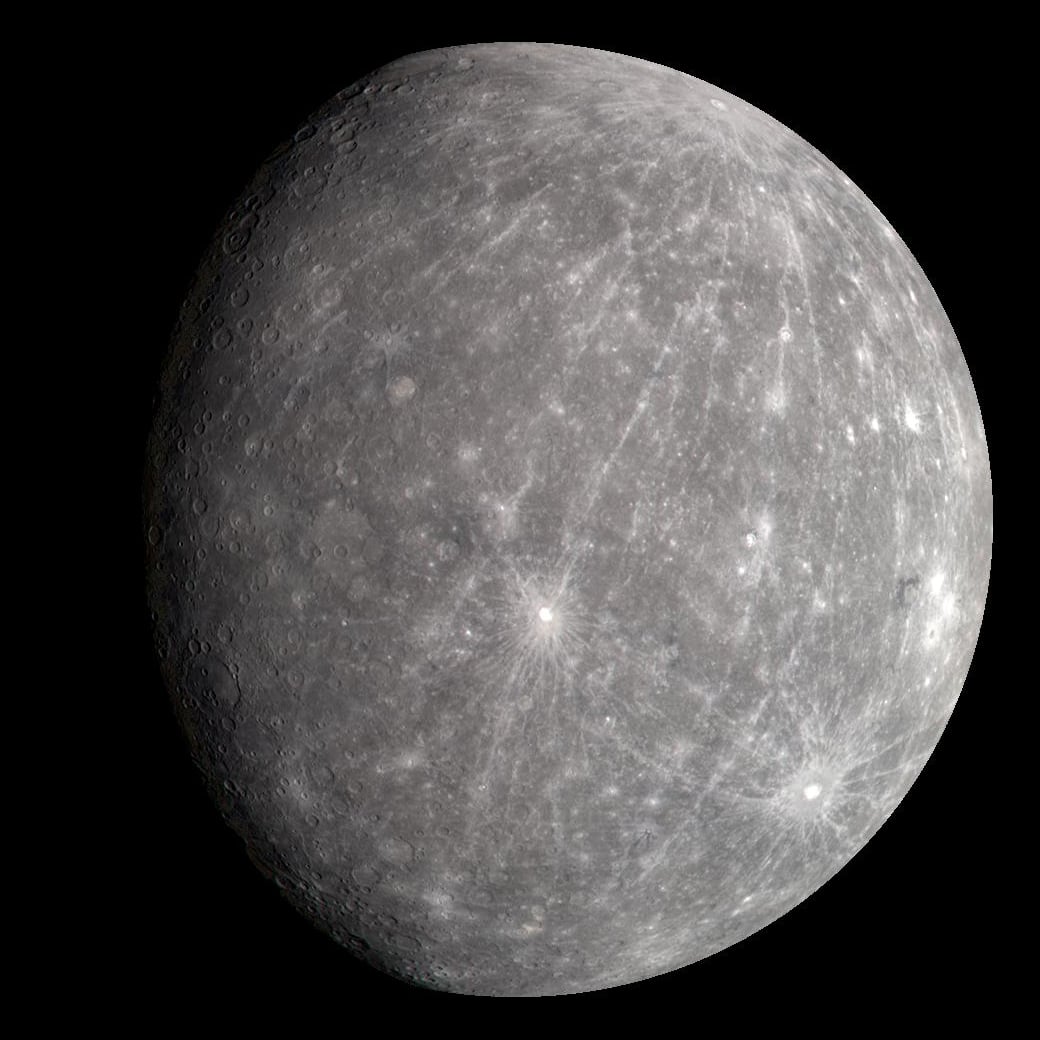

Researchers using machine learning have discovered hundreds of mysterious bright streaks on Mercury's surface that appear to be caused by gases escaping from the planet's interior. The finding suggests the Solar System's smallest planet isn't the static, geologically dead world we thought it was, Mercury might still be active today, continuously releasing material into space even billions of years after its formation.

Continue reading

Our current understanding of the Cosmos shows that structures emerge hierarchically. First there are dark matter densities, then dwarf galaxies. Those dwarfs then merge to form more massive galaxies, which merge together into even larger galaxies. Evidence of dwarf galaxy mergers is difficult to obtain, but new research found some in the Milky Way's halo.

Continue reading

Universe Today

Universe Today