Although the peak of the Geminid meteor shower has now passed, that doesn’t mean the activity will stop. For at least another week you’ll spot a rise in random activity that points back to the radiant of this reliable annual display. For most it will only be a bright streak that makes us yell out loud at its sudden beauty, but for some? We want the real dirt. We wanna’ know what’s really going on inside of Phaeton Place…

First noted in 1862 by Robert P. Greg in England, and B. V. Marsh and Prof. Alex C. Twining of the United States in independent studies, the annual appearance of the Geminid stream was weak, producing no more than a few per hour, but it has grown in intensity during the last century and a half. By 1877 astronomers were realizing that a new annual shower was occurring with an hourly rate of about 14. At the turn of the century it had increased to an average of over 20, and by the 1930s to from 40 to 70 per hour. Only ten years ago observers recorded an outstanding 110 per hour during a moonless night.

So why are the Geminids such a mystery? Most meteor showers are historic, documented and recorded for hundred of years, and we know them as being cometary debris. When astronomers first began looking for the Geminids’ parent comet, they found none. After decades of searching, it wasn’t until October 11, 1983 that Simon Green and John K. Davies, using data from NASA’s Infrared Astronomical Satellite, detected an orbital object which the next night was confirmed by Charles Kowal to match the Geminid meteoroid stream. But this was no comet, it was an asteroid.

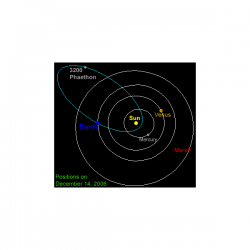

Originally designated as 1983 TB, but later renamed 3200 Phaethon, this apparently rocky solar system member has a highly elliptical orbit that places it within 0.15 AU of the Sun about every year and half. But asteroids can’t fragment like a comet – or can they? The original hypothesis was that since Phaethon’s orbit passes through the asteroid belt, it may have collided with other asteroids, creating rocky debris. This sounded good, but the more we studied the more we realized the meteoroid “path” occurred when Phaethon neared the Sun. So now our asteroid is behaving like a comet, yet it doesn’t develop a tail.

So what exactly is this “thing?” Well, we do know that 3200 Phaethon orbits like a comet, yet has the spectral signature of an asteroid. By studying photographs of the meteor showers, scientists have determined that the meteors are more dense than cometary material but not as dense as asteroid fragments. This leads us to believe that Phaethon is probably an extinct comet that has gathered a thick layer of interplanetary dust during its travels, yet retains the ice-like nucleus. Until we are able to take physical samples of this “mystery,” we may never fully understand what Phaethon is, but we can fully appreciate the annual display it produces.

So what exactly is this “thing?” Well, we do know that 3200 Phaethon orbits like a comet, yet has the spectral signature of an asteroid. By studying photographs of the meteor showers, scientists have determined that the meteors are more dense than cometary material but not as dense as asteroid fragments. This leads us to believe that Phaethon is probably an extinct comet that has gathered a thick layer of interplanetary dust during its travels, yet retains the ice-like nucleus. Until we are able to take physical samples of this “mystery,” we may never fully understand what Phaethon is, but we can fully appreciate the annual display it produces.

But I promised you dirt, didn’t I? Then let’s take an even better look at “Phaeton Place”…

If you happened to catch one of these bright meteor displays, you may have noticed it seemed to hang around a little bit longer. There’s good reason for that. The speed at which them Geminids hit our atmosphere is around 80,000 mph, about half that of the mighty Leonids. So what can cause that? Let’s ask meteor expert Wayne Hally.

“There are three factors which combine to create a meteor’s starting speed in the atmosphere. The minimum speed is around 11 kilometers per second…this is due solely to the Earth’s gravity. A particle that has a speed of zero relative to the Earth, will be drawn in by gravity until it is traveling just over 11kps when it reaches meteor height (~100km). The second factor is the particle’s motion around the Sun, and can range up to 42 kps at the Earth’s orbital distance. Anything moving faster is not in orbit around the Sun, and is either passing through the solar system or has been accelerated by interaction with a solar system object and is on it’s way out. These are VERY rare. Meteor shower particles must be in orbit, since we pass them as our orbits intersect each year.” says Halley. “Finally there is the Earth’s motion around the sun..we are moving around 30 kps in our own orbit, so we are adding our own motion to that of the particle around the Sun. So showers with slow speeds (< 30 kps) are catching up to us from behind. Meanwhile, the fastest showers, such as the leonids, are moving at high speed in a retrograde orbit (opposite that of the Earth) and smash into our windshield (the atmosphere) at the highest speed. (~72 kps). (BTW, the theoretical fastest speed is not 72+30+11 kps, rather it is about 72.9 kps...the speeds are not added directly....it is the square root of the sum of the squares....to explain it simply, a particle moving 72 kps has less time to be accelerated and only reaches 73, while a particle whose speed is zero has lots of time to be accelerated by gravity so winds up at 11 kps)."

“There are three factors which combine to create a meteor’s starting speed in the atmosphere. The minimum speed is around 11 kilometers per second…this is due solely to the Earth’s gravity. A particle that has a speed of zero relative to the Earth, will be drawn in by gravity until it is traveling just over 11kps when it reaches meteor height (~100km). The second factor is the particle’s motion around the Sun, and can range up to 42 kps at the Earth’s orbital distance. Anything moving faster is not in orbit around the Sun, and is either passing through the solar system or has been accelerated by interaction with a solar system object and is on it’s way out. These are VERY rare. Meteor shower particles must be in orbit, since we pass them as our orbits intersect each year.” says Halley. “Finally there is the Earth’s motion around the sun..we are moving around 30 kps in our own orbit, so we are adding our own motion to that of the particle around the Sun. So showers with slow speeds (< 30 kps) are catching up to us from behind. Meanwhile, the fastest showers, such as the leonids, are moving at high speed in a retrograde orbit (opposite that of the Earth) and smash into our windshield (the atmosphere) at the highest speed. (~72 kps). (BTW, the theoretical fastest speed is not 72+30+11 kps, rather it is about 72.9 kps...the speeds are not added directly....it is the square root of the sum of the squares....to explain it simply, a particle moving 72 kps has less time to be accelerated and only reaches 73, while a particle whose speed is zero has lots of time to be accelerated by gravity so winds up at 11 kps)."

Want even more dirt? The Geminid meteor shower rate has been continually increasing as well. “The Geminids are strong-and getting stronger,” says Bill Cooke of NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office. Just like a giant vacuum cleaner sucking up the dirt from our homes, so Jupiter has been busy attracting the meteoroid stream and drawing it closer and closer to Earth’s orbit. Meteor expert Peter Brown of the University of Western Ontario (UWO) says the trend could continue for some time to come. “Based on modeling of the debris done by Jim Jones in the UWO meteor group back in the 1980s, it is likely that Geminid activity will increase for the next few decades, perhaps getting 20% to 50% higher than current rates.”

Want even more dirt? The Geminid meteor shower rate has been continually increasing as well. “The Geminids are strong-and getting stronger,” says Bill Cooke of NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office. Just like a giant vacuum cleaner sucking up the dirt from our homes, so Jupiter has been busy attracting the meteoroid stream and drawing it closer and closer to Earth’s orbit. Meteor expert Peter Brown of the University of Western Ontario (UWO) says the trend could continue for some time to come. “Based on modeling of the debris done by Jim Jones in the UWO meteor group back in the 1980s, it is likely that Geminid activity will increase for the next few decades, perhaps getting 20% to 50% higher than current rates.”

Eventually this annual meteor shower could become a regular fireball showcase! And we’ll all be watching Phaeton Place…

Image Credits: Geminid Still Shots and Video – Courtesy of John Chumack, Geminid Still Photo – Courtesy of Haplo, Phaeton Orbit Plot – Courtesy of Randy Russell (UCAR), Geminid Meteor Rate Chart – Bill Cooke, NASA Meteoroid Environment Office. We thank you so much!

I did watched and… They were in the hundreds!

I took some pictures, I leave you here one of the bests (because the meteor was one of the largest we spotted).

http://www.haplo.com.mx/fotoblog/2009/12/14/geminidas/

Going to miss these ones, been extremely cloudy and cold here in Minnesota this week.

very nice, haplo! i picked up a little green and yellow coloration in the trail in your photo – a spectral signature that shows some iron and magnesium!

check out your other photos… do the same colors come out? chances are they aren’t artifacts, because most of the trails i observed visually definitely had some blue coloration which would denote heavy iron and magnesium concentrations.

science is so fun!!

😀

Loads of clear nights lately in the UK and on Sunday it was cloudy – bah! If you have celestia NEA.zip contains phaethon so you can watch the orbit.

I’m sorry. The first photo in the posting doesn’t have all the steaks originating from the same point. Can anyone explain?

i know it might look a little confusing, but almost the whole visible sky portion of the first photograph IS the constellation of gemini. i know it’s a little hard to see because the “all sky” cam picks up certain brighter stars and washes out others – but they are all basically aimed towards the same source.

now, if you were outside watching and a meteor came out of the south heading north? then it would be a sporadic and not considered part of a specific shower.

however!!

right now we are also cruising through the ursid meteorid stream, too. this can cause a handful of meteors you see to eminate more from the direction of ursa major (north) that from the more easterly gemini.

hope this helps!

Iron and magnesium! Great!

And some do look yellow/green, others look blue/whitish.

And you put up my pic, great!

Best regards! 🙂