Now we know why Japan’s lunar lander wasn’t able to recharge its batteries after touching down on the moon last week: The spacecraft appears to have tumbled onto its side, with its solar cells facing away from the sun.

The good news is that the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon, or SLIM, achieved its primary mission of setting down within 100 meters (330 feet) of its target point — and that the mission’s two mini-probes, which were ejected during SLIM’s descent, are working as intended.

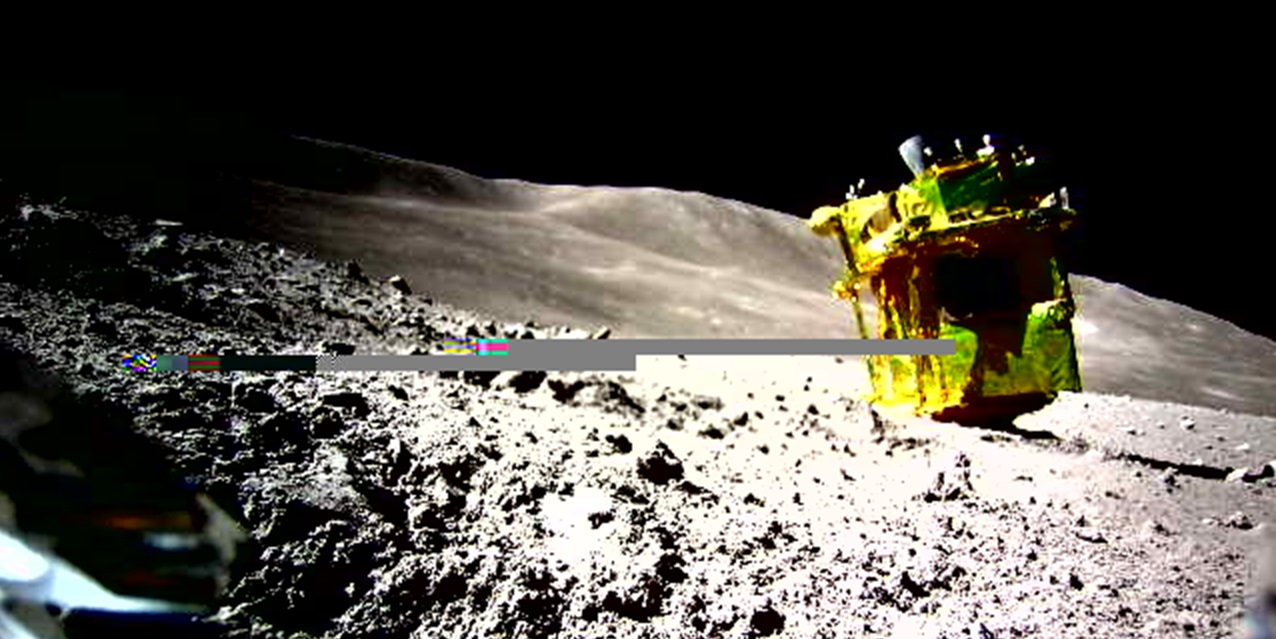

Scores of images were taken before and after landing. One of the pictures. captured by a camera on the ball-shaped LEV-2 mini-probe, shows the lander sitting at an odd angle with its thrusters facing upward and its solar cells facing westward.

To conserve battery power, mission managers at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency shut down SLIM after the probes transmitted the imagery they collected. But there’s still a chance that the sun’s shifting rays could provide enough power to allow for further operations in the week ahead.

JAXA project manager Shinichiro Sakai accentuated the positive as he showed off a photo from the mission. “Something we designed traveled all the way to the moon and took that snapshot,” he said. “I almost fell down when I saw it.”

Scientists gave fanciful names to the rocks visible in the pictures — including St. Bernard, Bulldog and Toy Poodle.

Mission managers analyzed the imagery as well as spacecraft data to figure out what happened to SLIM. One of the lander’s two main engines apparently malfunctioned during the descent, and the other main engine tried to compensate. The mission team said that the spacecraft touched down about 55 meters east of the target point near Shioli Crater — and that SLIM could have landed within 4 meters of the target if both engines had been working.

Despite the setbacks, Sakai said the “Moon Sniper” landing came close enough to rate the mission a success. “We demonstrated that we can land where we want,” he said. In the past, most interplanetary landing missions have had to plan for wider margins of error. NASA’s Perseverance rover, for example, targeted a 7.7-kilometer-wide landing ellipse in 2021.

SLIM’s landing site is illuminated by sunlight until Feb. 1, and researchers are hoping that as the sun heads toward the west in lunar skies, the lander’s solar cells will soak up enough light to allow for the resumption of powered operations. If the lander can be revived, the first priority will be to conduct high-resolution spectroscopic observations of the surroundings.

But SLIM’s time is extremely limited: During the 14 dark days that follow lunar sunset, falling temperatures are expected to put the lander into a deep freeze. “SLIM is not designed to survive a lunar night,” Sakai said.

Even if the lander can’t be revived, the ability to put a robotic spacecraft safely on the moon marks a triumph for Japan’s space effort. Only four other countries — the United States, Russia, China and India — have achieved similar feats.