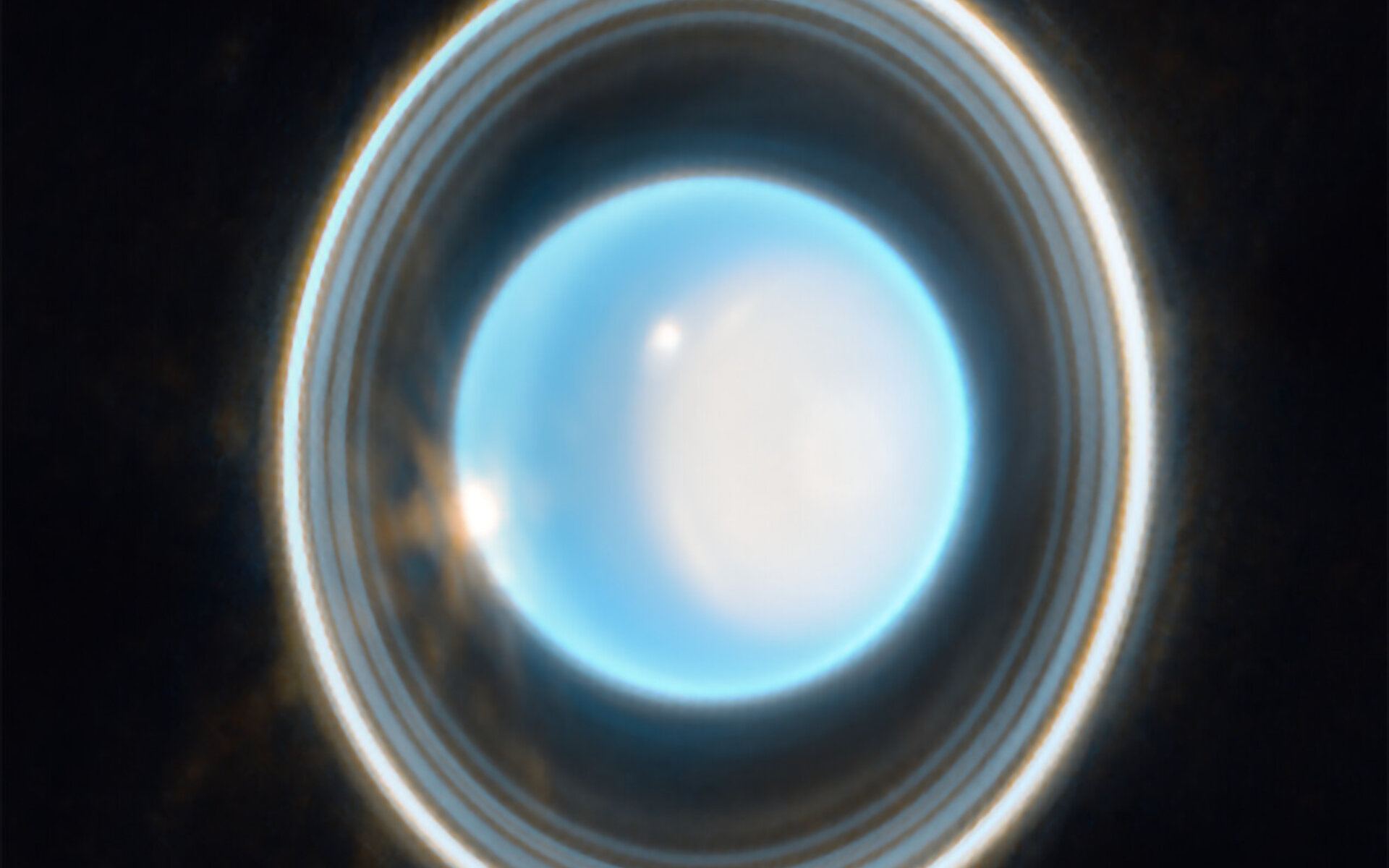

It seems crazy that Uranus was discovered in 1781 yet here we are, in 2024 and we have only sent one spacecraft to explore Uranus. Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft to have given us close-up images of Uranus (and Neptune) but since their visit in 1986, we have not returned. There have of course been great images from the Hubble Space Telescope and from the James Webb Space Telescope but we still have lots to learn about them.

The discovery of Uranus was accidental! British astronomer William Herschel was surveying stars that were too faint to see with the naked eye. One star caught his attention as it seemed to move agasinst the fixed background of stars. He assumed therefore that it was closer than the more distant, background stars. Initially he thought it was a comet but it was soon realised that it was a new planet. It was Uranus

Our knowledge of Uranus was quite limited until the advent of space exploration, in particular the Voyager spacecraft. Voyager 2 was launched on 20 August 1977 via the Titan Centaur rocket. Following flybys of Jupiter and Saturn in 1979 and 1981 respectively, it visited Uranus in 1986. Voyager 2 revealed a world with a lack of internal heat, a warmer than expected thermosphere and a magnetic field offset from the planets rotational axis. Other than that, Uranus has been sitting quitely minding its own business, being observed from afar through our best space telescopes.

There are however, many questions and uncertainties around the seventh planet from the Sun; from the nature of its interior and the interactions with the magnetic field to the mechanisms that shape the planet we see today. Without a doubt, a dedicated Uranian mission would help to unravel some of these mysteries.

It’s not just the paper that has been recently published by Emma K Dahl and team that recommends a Uranus Orbiter and Probe but a survey compiled by the National Academies of Sciences, Egineering and Medicine (NASEM) also found the same conclusion. A mission that could monitor Uranus over the long term would be invaluable in unlocking more details about the atmosphere; how the planet formed and how it has migrated around the Solar System? how the atmosphere has contributed to the evolution of the planet?; what processes are underway in the Uranian atmosphere and much more.

Unlocking some of these mysteries will not only help us to understand the nature or Uranus but also help us to understand how the Solar System and other planetary systems form. The paper goes further though, not just discussing the key outstanding questions but also looking at the measurements needed to derive conclusions and hypotheses from temperature and pressure profiles, chemical concentrations, wind speeds, vertical convection levels and magnetic field strengths to name a few.

There is a huge level of support across the science community for a mission to Uranus and not just an orbiter, a probe that can offer long term readings and observations. The recommendations from the NASEM review highlight the areas of focus and, if addressed, will help to finally unravel some of the mysteries of Uranus.