It’s hard to believe, but Mars Curiosity Rover has been on Mars doing its thing for 11 years. And, so what’s it doing to celebrate? Heading up a hill, making one of its toughest climbs ever.

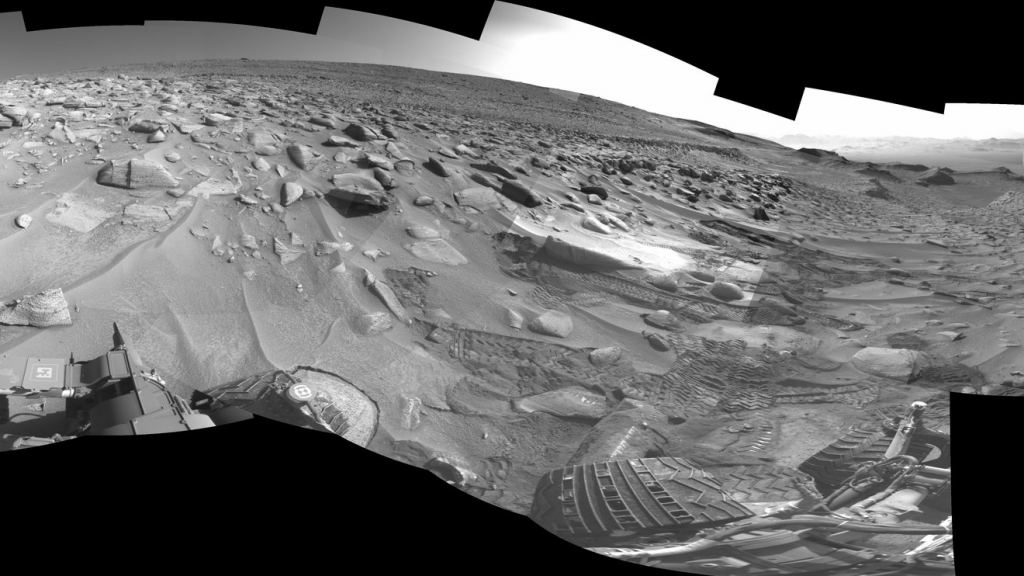

The “little rover that could” recently faced a particularly rough spot in its journey up Mount Sharp. That’s a 5 km tall mountain in the center of Gale Crater, where Curiosity landed in 2012. The path hasn’t been an easy one. The latest portion of the trip challenged the rover with a steep 23-degree incline, wheel-sized rocks, and slippery sand pits. According its controllers, it’s been a rough few months. But, the rover has made it through, so far.

“If you’ve ever tried running up a sand dune on a beach—and that’s essentially what we were doing—you know it’s hard, but there were boulders in there as well,” said Amy Hale, one of Curiosity’s drivers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

On the Road to Jau

The Jau region is one “pit stop” on the road up Mount Sharp. It’s pitted with dozens of small craters. Mission scientists don’t get to see that many craters all at once, so it was a great place to study them. However, getting to Jau posed dangers the mission drivers had to plan around. Hale and other “rover planners” write hundreds of lines of code to command the rover each day. They examine images from the rover to look for hazards that might stop or slow it down. Everyone keeps an eye out for sand pits or other obstacles, too.

Drivers then work with mission scientists to figure out what the next moves will be. They send revised code to Mars overnight so the rover can implement it the next day. That’s what happened with the traverse to Jau. Curiosity wasn’t in any danger while getting there, but drivers had to contend with sudden events when the rover would stop due to something unforeseen. They called those “faults” and there were plenty of them along the way to Jau.

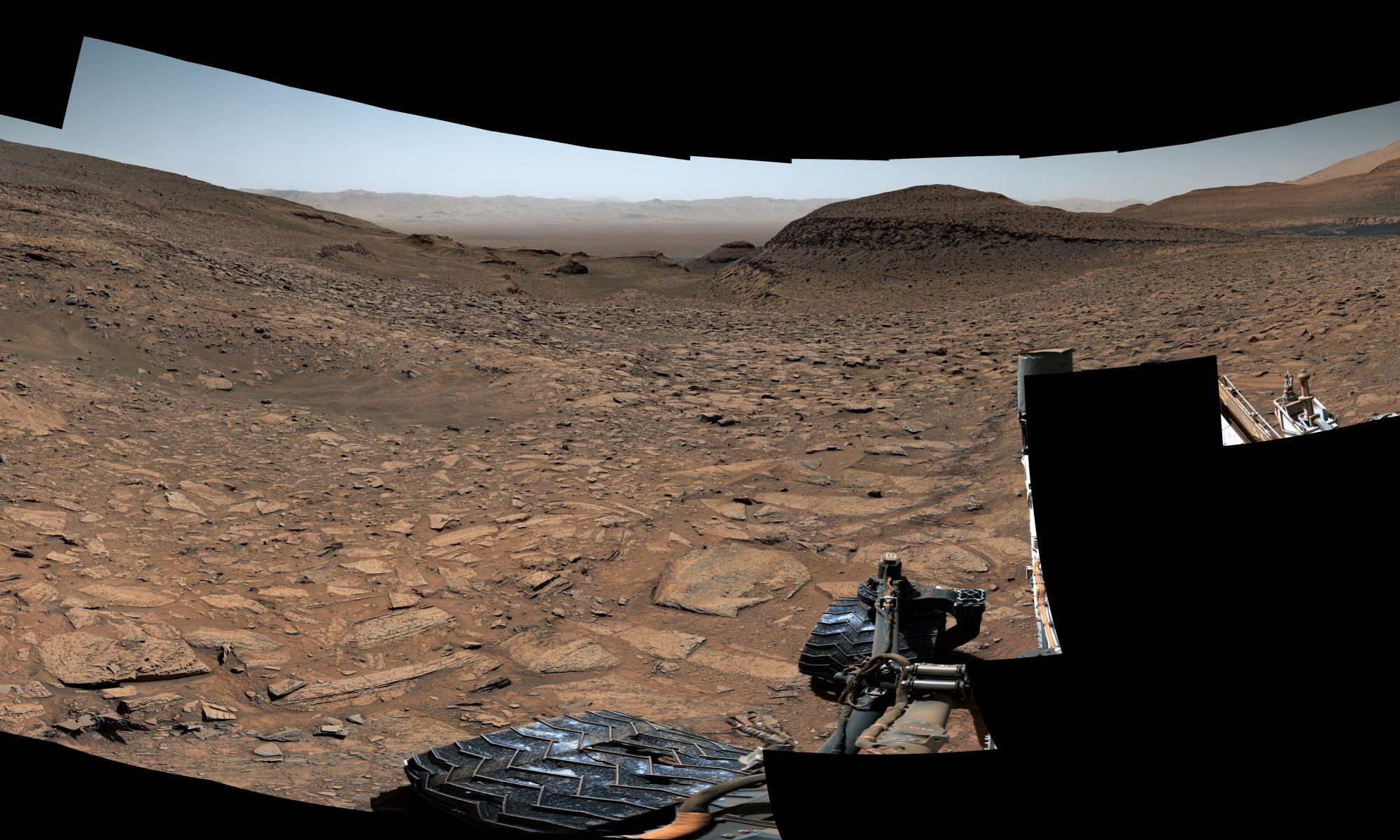

At one point, the rover drivers and scientists programmed a detour to help the rover avoid some troublesome terrain. That added a few weeks on the journey. “It felt great to finally get over the ridge and see that amazing vista,” Schoelen said. “I get to look at images of Mars all day long, so I really get a sense of the landscape. I often feel like I’m standing right there next to Curiosity, looking back at how far it has climbed.”

Exploring Jau

Jau region is a crater cluster slopes of Mount Sharp. At least one crater is filled with sand and broken rock slabs pave the area. Interestingly, the Jau area, like all of the Mount Sharp region, was once populated by lakes, rivers, and streams. Then, the climate changed and shaped the Mars we see today. Curiosity is sampling the rocks and other materials here to help scientists understand what that early environment was like. It finds strong evidence for water and waves on ancient Mars.

In Jau, the rocks and sand were likely part of the sediments laid down in the past. It’s also likely that some of those sands were deposited by the action of the Martian winds. The crater cluster probably formed when a meteor broke up in the atmosphere and showered the surface with fragments of the original. Now, planetary scientists want to know if the salt-enriched surface terrain had an effect on the way those craters formed and eroded after the impact.

Mount Sharp (its official name is Aeolis Mons), is actually the central peak of an impact crater. Its made up of layers of eroded sedimentary rock laid down before the crater formed. Other layers of material in the crater could have come from later lake deposits. Scientists estimate that some of those layers got deposited at least 3 to 3.5 billion years ago. Now they want to know if that lake could have hosted some form of life in those ancient times.

For More Information

NASA’s Curiosity Rover Faces Its Toughest Climb Yet on Mars

About Mount Sharp