Way out in the universe, a long time ago, a proto-magnetar was born. The birth was heralded by a gamma-ray burst (GRB), followed by a blast of strange emissions. Astronomers once assumed that GRBs like this came from black hole births. However, observations of the new object by astronomers in England show there’s more than one way to cause a GRB. And, there’s more than one type of GRB.

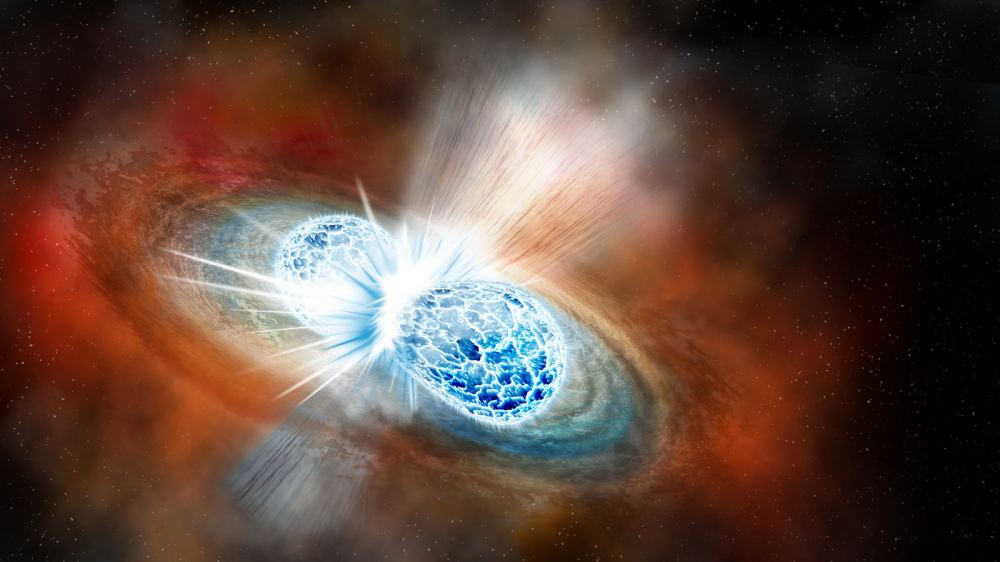

The science team, headed by Dr. Nuria Jordana-Mitjans at the University of Bath, studied a wide range of electromagnetic radiation blasting out from an object called GRB 180618A. It lies in the outskirts of a galaxy about five billion light-years away from us. The object emitted a “short-duration GRB” followed by other rapid bursts of other emissions that faded quickly. The whole thing was triggered by the collision of two neutron stars. However, instead of merging to create a black hole, they made something new. It was a neutron star remnant, supra-massive star also known as a proto-magnetar.

“For the first time, our observations highlight multiple signals from a surviving neutron star that lived for at least one day after the death of the original neutron star binary,” she said.

Gamma-ray Burst Aftermath

A gamma-ray burst always accompanies a pretty spectacular event. Most of them last only a short time before fading out. So, astronomers are in a race against time to focus on the burst and the afterglow before it fades out. All their observations give clues about what caused the GRB in the first place. In the case of GRB 180618A, quick observations revealed some very intriguing clues.

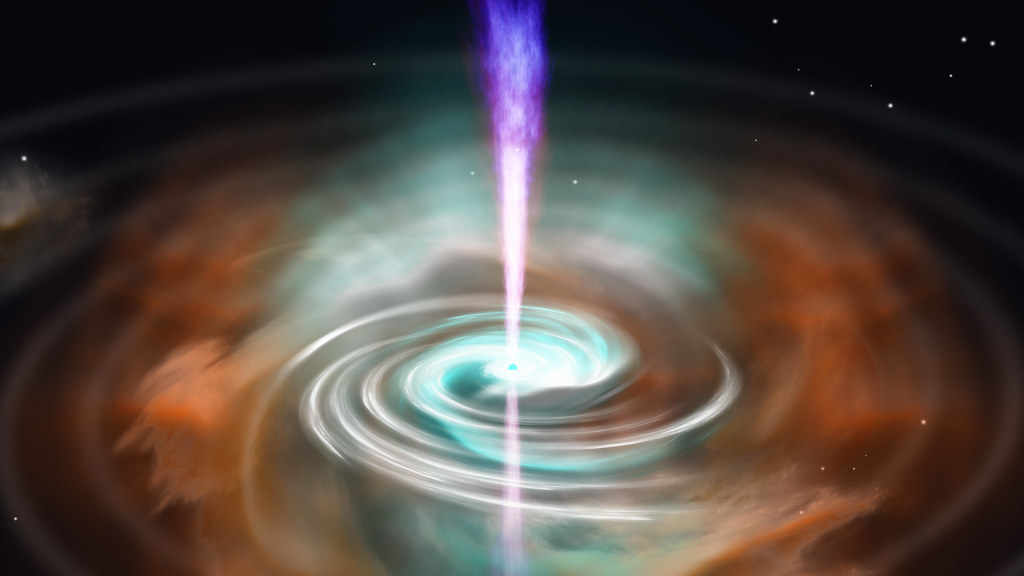

The mechanics of this gamma-ray burst and its aftermath are interesting. It began with the two ultra-dense “progenitor” neutron stars spiraling around together, getting closer and closer. Eventually, they collided. Just moments before the collision, gravitational waves rushed away from the site. Then, the collision happened and triggered the GRB. What remained after the merger was the remnant, a rapidly spinning newborn magnetar. Its radiation powered a hot nebula expanding very rapidly away from the merger site.

The birth of the supra-massive neutron star remnant has opened up a whole new field of study for gamma-ray burst progenitors. “Such findings are important as they confirm that newborn neutron stars can power some short-duration GRBs and the bright emissions across the electromagnetic spectrum that have been detected accompanying them,” said Dr. Jordana-Mitjens.

Puzzling Out What Happened

Short-duration GRBs like this one are interesting but not completely well-understood. What astronomers do know is intriguing. Typically, they do happen when two neutron stars collide. That produces a jetted explosion that first releases a huge amount of gamma radiation. After that, what’s left is usually some kind of debris.

The emissions from GRB 180618A indicated to Dr. Jordana-Mitjans that a neutron star remnant was created in the merger. The sequence of emissions that followed didn’t fit the game plan of most GRBs after the initial blast. Sure, this one included an optical light afterglow. But, it disappeared after only 35 minutes. That’s pretty fast, compared to some GRB afterglows that fade after days or weeks.

The team analyzed the data further and found that the material giving off the afterglow was expanding at close to the speed of light. As it expands, it cools, which could explain why it didn’t show up for too long. But, the bigger question was: what was pushing it from behind? That was the magnetar. It heated up the material of the crash left over after its progenitor neutron stars collided.

What’s Next?

In GRB studies, it’s important to catch the event as soon as possible. It’s the only way to figure out what causes one. The GRB flash itself happens very quickly. Astronomers have to act fast to get enough data about it and afterglow. To give an idea—everything can happen in a matter of seconds or minutes. Once the outburst site is located in the sky, then other telescopes can jump in and look for signals in other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Fortunately, the team studying GRB 180618A was able to look at the immediate aftermath of the GRB flash. Their data came from the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, which is tuned to look for these high-energy outbursts. According to Professor Carole Mundell, study co-author and professor of Extragalactic Astronomy at Bath, the timing was almost perfect.

“We were excited to catch the very early optical light from this short gamma-ray burst – something that is still largely impossible to do without using a robotic telescope,” she said. “But when we analyzed our exquisite data, we were surprised to find we couldn’t explain it with the standard fast-collapse black hole model of GRBs. Our discovery opens new hope for upcoming sky surveys with telescopes such as the Rubin Observatory LSST with which we may find signals from hundreds of thousands of such long-lived neutron stars before they collapse to become black holes.”

There may well be other short-duration GRBs showing similar signals to those given off by GRB 180618A, according to Dr. Jordana-Mitjens. “This discovery may offer a new way to locate neutron star mergers, and thus gravitational waves emitters, when we’re searching the skies for signals,” she said.

For More Information

Black holes don’t always power gamma-ray bursts, new research shows

A Short Gamma-Ray Burst from a Protomagnetar Remnant