Clay is a big deal on Mars because it often forms in contact with water. Find clay, and you’ve usually found evidence of water. And the nature, history, and current water budget on Mars are all important to understanding that planet, and if it ever supported life.

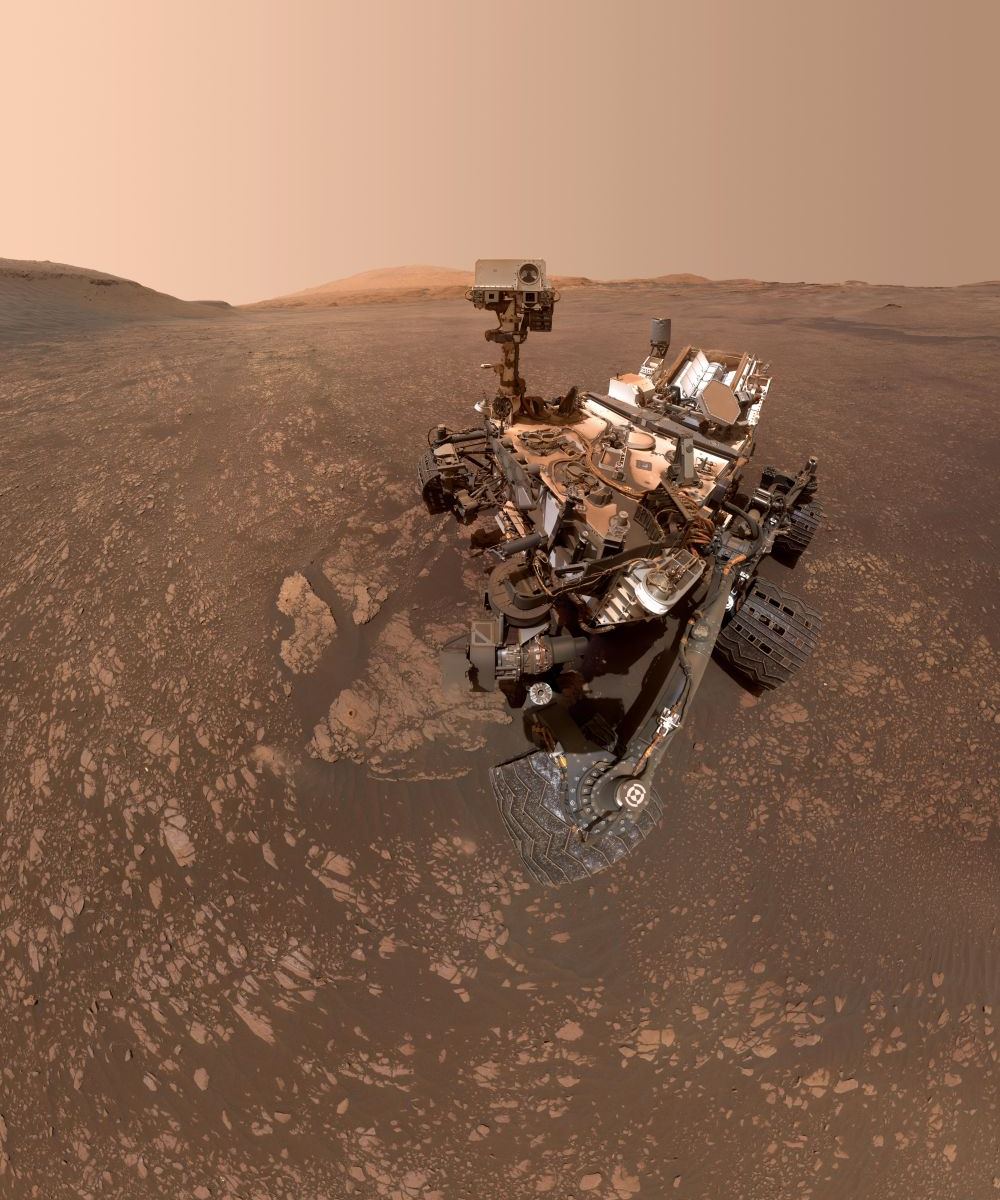

Right now, MSL Curiosity is at Mt. Sharp inspecting rocks for clay. Orbiters were the first to find evidence of clay at Mt. Sharp. When NASA chose Gale Crater as MSL Curiosity’s landing site, the clay at Mt. Sharp inside the crater was one of the objectives. Now Curiosity has sampled two of the rocks in what NASA’s calling the ‘clay-bearing unit’ and they’ve confirmed the presence of clay.

In fact, the two rocks show the highest concentrations of clay that Curiosity has found so far. The rocks are called “Aberlady” and “Kilmarie.” They’re located at the lower part of Mt. Sharp, which is the mission’s primary objective.

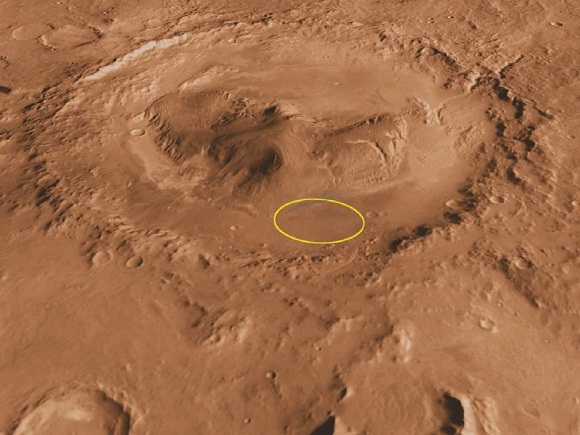

Mt. Sharp rises 5.5 km (18,000 ft.) above the crater floor, meaning it is an accessible, layered record of Martian geology. Over time, wind has exposed its different layers, making them easy targets for Curiosity’s drill.

Scientists are interested in Mt. Sharp, also called Aeolis Mons, because of how they think it formed. Gale Crater is an ancient impact crater that was likely filled with water, and they think that Mt. Sharp formed over a time period of two billion years, as sediment was deposited at the bottom of the lake. It’s possible that at one time the entire crater was filled with sediment, which gradually eroded, leaving Mt. Sharp behind.

There’s some uncertainty around the timeline of Mt. Sharp’s formation, which is one of the things MSL Curiosity hopes to uncover. In any case, Mt. Sharp itself appears to be an eroded mountain of sediment, and as Curiosity continues its work, scientists may finally get a clearer picture of how exactly it formed.

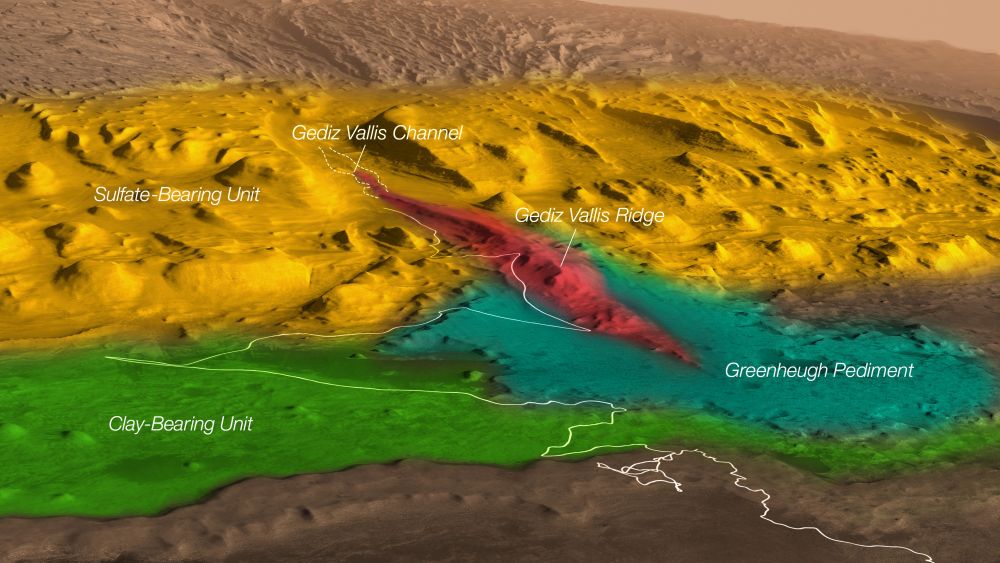

Curiosity’s new findings show that there was once an abundance of water in Gale Crater, as expected. But other than that, the details are still to be determined. It seems that these clay-rich rocks at the lower range of the mountain formed as sediment at the bottom of a lake. Over geological time periods, water and sediment interact to form clays.

Finding specific types of clays at specific layers tells scientists about the timeline of Martian water. We know that the mountain has different layers containing different minerals. As mentioned, the lower layers contain clays, but above that are layers containing sulfur, and above that are layers containing oxygen-bearing minerals. The sulfur indicates that the area dried out, or the water became more acidic.

Gale crater also contains a river channel called Gediz Vallis Channel, which formed after the clay and sulfur layers. That channel is also a piece of the puzzle, and Curiosity’s task is to continue its way up Mt. Sharp, sampling as it goes, and fill in the picture of the mountain’s geology and history. By extension, we’ll learn something about Martian history.

Curiosity will also give us a much more detailed view of the clay-bearing unit than orbiter’s gave us. Orbital readings couldn’t say for sure if the clay it sensed was in the bedrock of the mountain, or if it was from eroded pebbles and rocks that had eroded out of the upper layers of the mountain and tumbled down to the floor of the crater. Curiosity has clarified that to some degree, with the discovery of clay in Aberlady and Kilmarlie, but there’s still lots of work to do.

“Each layer of this mountain is a puzzle piece,” said Curiosity Project Scientist Ashwin Vasavada of JPL. “They each hold clues to a different era in Martian history.”

Curiosity is doing a fine job of piecing it all together.