Monday, September 17 – Today in 1789, William Herschel discovered Saturn’s moon Mimas. Tonight we’ll discover our own Moon as we have a look at one of the last lunar challenges that occur during the first few days of the Moon’s appearance – Piccolomini. You’ll find it to the southwest of the shallow ring of Fracastorius on Mare Nectaris’ southern shore.

Piccolomini is a standout lunar feature – mainly because it is a fairly fresh impact crater. Its walls have not yet been destroyed by later impacts and the interior is nicely terraced. Power up and look carefully at the northern interior wall where perhaps a rock slide has slipped towards the crater floor. While the floor itself is fairly featureless, the central peak is awesome. Rising up a minimum of two kilometers above the floor, it’s even higher than the White Mountains in New Hampshire!

Now let’s take a look at a double which has a close separation – Epsilon Lyrae. Known to most of us as the “Double Double,” look about a finger width northeast of Vega. Even the slightest optical aid will reveal this tiny star as a pair, but the real treat is with a telescope – for each component is a double star! Both sets of stars appear as primarily white and both are very close to each other in magnitude. What is the lowest power that you can use to split them?

Tuesday, September 18 – Tonight as the skies darken, look for the beautiful red Antares less than a degree north of the Moon. Such a close union might mean an occultation, so be sure to check IOTA! Also joining this celestial array is Jupiter just a few more degrees north.

Tonight we’ll use a well-known lunar feature to help guide us to another challenge that is a little less easy to identify – crater Plinius. Starting with the grand visage of Posidonius, trace your way south past the ruined walls of Le Monnier and look for the long north/south wrinkle of Dorsa Smirnov running parallel to the terminator. Where it ends in the Promontorium Archerusia, look for the bright circle of Plinius.

Spanning approximately 43 kilometers, it is far from a prominent crater, yet will remain a very bright ring as the Moon grows full. Formed by an impact, its walls are bright and sharp with an irregular floor and jagged central peaks that will appear at times like two small impact craters.

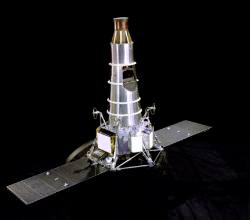

It is near this rather inconspicuous feature that the remains of Ranger 6 lay forever preserved after “crash-landing” on February 2nd, 1964. Unfortunately, technical errors prevented Ranger 6 from transmitting lunar pictures. Not so Ranger 8! On a very successful mission to the same basic area, NASA received 7137 “postcards from the near side of the Moon” for 23 minutes before a very hard landing. On the “softer side,” Surveyor 5 touched down near this area safely after two days of malfunctions on September 10, 1967. Incredibly, the tiny Surveyor 5 endured temperatures of up to 283 degrees F, but still spectrographically analyzed the area’s soil and also managed to televise over 18,000 frames of “home movies” from its distant lunar location.

Wednesday, September 19 – On this day in 1848, William Boyd was watching Saturn – and discovered its moon Hyperion. Also today in 1988, Israel launched its first satellite. How long has it been since you’ve watched an ISS pass or an iridium flare? Both are terrific events that don’t require any special equipment to be seen. Be sure to check with Heavens Above for accurate times and passes in your location and enjoy!

For binoculars and telescopes, the Moon will provide a piece of scenic history as we take an in-depth look at crater Albategnius. This huge, hexagonal mountain-walled plain will appear near the terminator about one-third the way north from the south limb. This 136 kilometer wide crater is approximately 4390 meters deep and the west wall will cast a black shadow on the dark floor. Albategnius is a very ancient formation, filled partially with lava at one point in its development, and is home to several wall craters like Klein (which will appear telescopically on its southwest wall). Albategnius holds more than just the distinction of being a prominent crater tonight – it holds a place in history. On May 9, 1962 Louis Smullin and Giorgio Fiocco of the Massachusetts Institute of technology aimed a red laser beam toward the lunar surface and Albategnius became the first lunar object to be illuminated and detected by a laser from Earth!

On March 24, 1965 Ranger 9 took this snapshot of Albategnius (in the lower right) from an altitude of approximately 2500 kilometers. Companion craters in the image are Ptolemaeus and Alphonsus, which will be revealed tomorrow night. Ranger 9 was designed by NASA for one purpose – to achieve a lunar impact trajectory and to send back high-resolution photographs and high-quality video images of the lunar surface. It carried no other scientific experiments, and its only destiny was to take pictures right up to the moment of final impact. It is interesting to note that Ranger 9 slammed into Alphonsus approximately 18.5 minutes after this photo was taken. They called that…a “hard landing.”

Thursday, September 20 – Let’s walk upon the Moon this evening as we take a look at sunrise over one of the most often studied and mysterious of all craters – Plato. Located on the northern edge of Mare Imbrium and spanning 95 kilometers in diameter, Class IV Plato is simply a feature that all lunar observers check because of the many reports of unusual happenings. Over the years, mists, flashes of light, areas of brightness and darkness, and the appearance of small craters have become a part of Plato’s lore.

On October 9, 1945 an observer sketched and reported “a minute, but brilliant flash of light” inside the western rim. Lunar Orbiter 4 photos later showed where a new impact may have occurred. While Plato’s interior craterlets average between less than one and up to slightly more than two kilometers in diameter, many times they can be observed – and sometimes they cannot be seen at all under almost identical lighting conditions. No matter how many times you observe this crater, it is ever changing and very worthy of your attention!

Now let the Moon head west, because on this night in 1948, the 48″ Schmidt telescope at Mt. Palomar was busy taking pictures. The first photographic plate was being exposed on a galaxy by the same man who ground and polished the corrector plate for this scope – Hendricks. His object of choice was reproduced as panel 18 in the Hubble Atlas of Galaxies and tonight we’ll join his vision as we take a look at the fantastic M31 – the Andromeda Galaxy.

Seasoned amateur astronomers can literally point to the sky and show you the location of M31, but perhaps you have never tried. Believe it or not, this is an easy galaxy to spot even under the moonlight. Simply identify the large diamond-shaped pattern of stars that is the “Great Square of Pegasus.” The northernmost star is Alpha, and it is here we will begin our hop. Stay with the north chain of stars and look four finger-widths away for an easily seen star. The next along the chain is about three finger-widths away… And we’re almost there. Two more finger-widths to the north and you will see a dimmer star that looks like it has something smudgy nearby. Point your binoculars there, because that’s no cloud – it’s the Andromeda Galaxy!

Friday, September 21 – Tonight’s featured lunar crater will be located on the south shore of Mare Imbrium right where the Apennine mountain range meets the terminator. Eratosthenes is unmistakable at 58 kilometers in diameter and 375 meters deep. Named after the ancient mathematician, geographer and astronomer Eratosthenes, this splendid Class 1 crater will display a bright west wall and a deep interior which contains its massive crater-capped central mountain reaching up to 3570 meters high! Extending like a tail, an 80 kilometer long mountain ridge angles away to the southwest. As beautiful as Eratosthenes appears tonight, it will fade away to total obscurity as the Moon becomes more Full. See if you can spot it in five days!

Now let’s journey to a very pretty starfield as we head toward the western wingtip in Cygnus to have a look at Theta – also known as 13 Cygni. It is a beautiful main sequence star that is also considered by modern catalogs to be a double. For large telescopes, look for a faint (13th magnitude) companion to the west… But it’s also a wonderful optical triple!

Also in the field with Theta to the southeast is the Mira-type variable R Cygni, which ranges in magnitude from around 7 to 14 in slightly less than 430 days. This pulsating red star has a really quite interesting history that can be found at AAVSO, and is circumpolar for far northern observers. Check it out!

Saturday, September 22 – Tonight on the Moon, let’s take an in-depth look at one of the most impressive of the southern lunar features – Clavius.

Although you cannot help but be drawn visually to this crater, let’s start at the southern limb near the terminator and work our way up. Your first sighting will be the large and shallow dual rings of Casatus with its central crater and Klaproth adjoining it. Further north is Blancanus with its series of very small interior craters, but wait until you see Clavius. Caught on the southeast wall is Rutherford with its central peak and crater Porter on the northeast wall. Look between them for the deep depression labeled D. West of D you will also see three outstanding impacts: C, N and J; while CB resides between D and Porter. The southern and southwest walls are also home to many impacts, and look carefully at the floor for many, many more! It has been often used as a test of a telescope’s resolving power to see just how many more craters you can find inside tremendous old Clavius. Power up and enjoy!

Now let’s head for the northeast corner of the little parallelogram that is part of Lyra for easy unaided eye and binocular double Delta 1 and 2 Lyrae.

The westernmost Delta 1 is about 1100 light-years away and is a class B dwarf, but take a closer look at brighter Delta 2. This M-class giant is only 900 light-years away. Perhaps 75 million years ago, it, too, was a B class star, but it now has a dead helium core and it keeps on growing. While it is now a slight variable, it may in the future become a Mira-type. A closer look will show that it also has a true binary system nearby – a tightly matched 11th magnitude system. Oddly enough they are the same distance away as Delta-2 and are believed to be physically related.

Sunday, September 23 – Today is the Autumnal Equinox. This marks the first day of the fall season for the Northern Hemisphere and we astronomers welcome back earlier dark skies! On this day in 1846, Johann Galle of the Berlin Observatory makes a visual discovery. While at the telescope, Galle sees and identifies the planet Neptune for the first time in history. Would you like to try for Neptune? It’s fairly easy – especially seeing as how it’s only about a degree north of the Moon tonight! This could be an occultation event for some areas, so be sure to check IOTA!

Tonight exploring the Moon will be in order as one of the most graceful and recognizable lunar features will be prominent – Gassendi. As an ancient mountain-walled plain that sits proudly at the northern edge of Mare Humorum, Gassendi sports a bright ring and a triple central mountain peak that are within the range of binoculars.

Telescopic viewers will appreciate Gassendi at high power in order to see how its southern border has been eroded by lava flow. Also of note are the many rilles and ridges that exist inside the crater and the presence of the younger Gassendi A on the north wall. While viewing the Mare Humorum area, keep in mind that we are looking at an area about the size of the state of Arkansas. It is believed that a planetoid collision originally formed Mare Humorum. The incredible impact crushed the surface layers of the Moon resulting in a concentric “anticline” that can be traced out to twice the size of the original impact area. The floor of this huge crater then filled in with lava, and was once thought to have a greenish appearance but in recent years has more accurately been described as reddish. That’s one mighty big crater!

On this day in 1962, the prime time cartoon “The Jetsons” premiered. Think of all the technology this inspired as tonight we kick back to watch the Alpha Aurigid meteor shower. Relax, face northeast and look for the radiant near Capella. The fall rate is around 12 per hour, and they are fast and leave trails!

Monday, September 24 – In 1970, the first unmanned, automated return of lunar material to the Earth occurred on this day when the Soviet’s Luna 16 returned with three ounces of the Moon. Its landing site was eastern Mare Fecunditatis. Look just west of the bright patch of Langrenus.

Tonight our primary lunar study is crater Kepler. Look for it as a bright point, slightly lunar north of center near the terminator. Its home is the Oceanus Procellarum – a sprawling dark mare composed primarily of dark minerals of low reflectivity (albedo) such as iron and magnesium. Bright, young Kepler will display a wonderfully developed ray system. The crater rim is very bright, consisting mostly of a pale rock called anorthosite. The “lines” extending from Kepler are fragments that were splashed out and flung across the lunar surface when the impact occurred. The region is also home to features known as “domes” – seen between the crater and the Carpathian Mountains. So unique is Kepler’s geological formation that it became the first crater mapped by U.S. Geological Survey in 1962.

Tuesday, September 25 – Tonight Uranus will be a little less than two degrees south of the Moon, but we’re going to have a look at a lunar feature that goes beyond simply incredible – it’s downright weird. Start your journey by identifying Kepler and head due west across Oceanus Procellarum until you encounter the bright ring of crater Reiner. Spanning 30 kilometers, this crater isn’t anything in particular – just shallow-looking walls with a little hummock in the center. But, look further west and a little more north for an anomaly – Reiner Gamma.

Well, it’s bright. It’s slightly eye-shaped. But what exactly is it? Possessing no real elevation or depth above the lunar surface, Reiner Gamma could very well be an extremely young feature caused by a comet. Only three other such features exist – two on the lunar far side and one on Mercury. They are high albedo surface deposits with magnetic properties. Unlike a lunar ray of material ejected from below the surface, Reiner Gamma can be spotted during the daylight hours – when ray systems disappear. And, unlike other lunar formations, it never casts a shadow.

Reiner Gamma also causes a magnetic deviation on a barren world that has no magnetic field. This has many proposed origins, such as solar storms, volcanic gaseous activity, or even seismic waves. But, one of the best explanations for its presence is a cometary strike. It is believed that a split-nucleus comet, or cometary fragments, once impacted the area and the swirl of gases from the high velocity debris may have somehow changed the regolith. On the other hand, ejecta from an impact could have formed around a magnetic “hot spot,” much like a magnet attracts iron filings.

No matter which theory is correct, the simple act of viewing Reiner Gamma and realizing that it is different from all other features on the Moon’s earthward facing side makes this journey worth the time!

Wednesday, September 26 – This is the Universal date the Moon will become Full and it will be the closest to the Autumnal Equinox. Because its orbit is more nearly parallel to the eastern horizon, it will rise at dusk for the next several nights in a row. On the average, the Moon rises about 50 minutes later each night, but at this time of year it’s around 20 minutes later for mid-northern latitudes and even less farther north. Because of this added light, the name “Harvest Moon” came about because it allowed farmers more time to work in the fields.

Often times we perceive the Harvest Moon as being more orange than at any other time of the year. The reason is not only scientific enough – but true. Coloration is caused by the scattering of the light by particles in our atmosphere. When the Moon is low, like now, we get more of that scattering effect and it truly does appear more orange. The very act of harvesting itself produces more dust and often times that coloration will last the whole night through. And we all know the size is only an “illusion”…

So, instead of cursing the Moon for hiding the deep sky gems tonight, enjoy it for what it is…a wonderful natural phenomenon that doesn’t even require a telescope!

And if you’d like to visit another object that only requires eyes, then look no further than Eta Aquilae one fist-width due south of Altair…

Discovered by Pigot in 1784, this Cepheid-class variable has a precision rate of change of over a magnitude in a period of 7.17644 days. During this time it will reach of maximum of magnitude 3.7 and decline slowly over 5 days to a minimum of 4.5… Yet it only takes two days to brighten again! This period of expansion and contraction makes Eta very unique. To help gauge these changes, compare Eta to Beta on Altair’s same southeast side. When Eta is at maximum, they will be about equal in brightness.

Thursday, September 27 – Tonight we’ll begin with an easy double star and make our way towards a more difficult one. Beautiful, bright and colorful, Beta Cygni is an excellent example of an easily split double star. As the second brightest star in the constellation of Cygnus, Albireo lies roughly in the center of the “Summer Triangle” making it a relatively simple target for even urban telescopes.

Albireo’s primary (or brightest) star is around magnitude 4 and has a striking orangish color. Its secondary (or B) star is slightly fainter at a bit less than magnitude 5, and often appears to most as blue, almost violet. The pair’s wide separation of 34″ makes Beta Cygni an easy split for all telescopes at modest power, and even for larger binoculars. At approximately 410 light-years away, this colorful pair shows a visual separation of about 4400 AU, or around 660 billion kilometers. As Burnham noted, “It is worth contemplating, in any case, the fact that at least 55 solar systems could be lined up, edge-to-edge, across the space that separates the components of this famous double!”

Now let’s have a look at Delta. Located around 270 light-years away, Delta is known to be a more difficult binary star. Its duplicity was discovered by F. Struve in 1830, and it is a very tough test for smaller optics. Located no more than 220 AU away from the magnitude 3 parent star, the companion orbits anywhere from 300 to 540 years and is often rated as dim as 8th magnitude. If skies aren’t steady enough to split it tonight, try again! Both Beta and Delta are on many challenge lists.

Friday, September 28 – Tonight we’ll have a look at the central star of the “Northern Cross” – Gamma Cygni. Also known as Sadr, this beautiful main sequence star lies at the northern edge of the “Great Rift.” Surrounded by a field of nebulosity known as IC 1310, second magnitude Gamma is very slowly approaching us, but still maintains an average distance of about 750 light-years. It is here in the rich, starry fields that the great dust cloud begins its stretch toward southern Centaurus – dividing the Milky Way into two streams. The dark region extending north of Gamma towards Deneb is often referred to as the “Northern Coalsack,” but its true designation is Lynds 906.

If you take a very close look at Sadr, you will find it has a well-separated 10th magnitude companion star, which is probably not related – yet in 1876, S. W. Burnham found that it itself is a very close double. Just to its north is NGC 6910, a roughly 6th magnitude open cluster which displays a nice concentration in a small telescope. To the west is Collinder 419, another bright gathering that is nicely concentrated. South is Dolidze 43, a widely spaced group with two brighter stars on its southern perimeter. East is Dolidze 10, which is far richer in stars of various magnitudes and contains at least three binary systems.

Whether you use binoculars or telescopes, chances are you won’t see much nebulosity in this region – but the sheer population of stars and objects in this area makes a visit with Sadr worthy of your time!

Saturday, September 29 – Tonight let’s head about a fingerwidth south of Gamma Cygni to have a look at an open cluster well suited for all optics – M29.

Discovered in 1764 by Charles Messier, this type D cluster has an overall brightness of about magnitude 7, but isn’t exactly rich in stars. Hanging out anywhere from 6000 to 7200 light-years away, one would assume this to be a very rich cluster and it may very well have hundreds of stars – but their light is blocked by a dust cloud a thousand times more dense than average.

Approaching us at around 28 kilometers per second, this loose grouping could be as old as 10 million years and appears much like a miniature of the constellation of Ursa Major at low powers. Even though it isn’t the most spectacular in star-rich Cygnus, it is another Messier object to add to your list!

Sunday, September 30 – Today in 1880, Henry Draper must have been up very early indeed when he took the first photo of the Great Orion Nebula (M42). Although you might not wish to set up equipment before dawn, you can still use a pair of binoculars to view this awesome nebula! You’ll find Orion high in the southeast for the Northern Hemisphere, and M42 in the center of the “sword” that hangs below its bright “belt” of three stars.

Tonight before the Moon rises and we leave Cygnus for the year, try your luck with IC 5070, also known as the “Pelican Nebula.” You’ll find it just about a degree southeast of Deneb and surrounding the binary star 56 Cygni.

Located around 2000 light-years away, the Pelican is an extension of the elusive North American Nebula, NGC 7000. Given its great expanse and faintness, catching the Pelican does require clean skies, but it can be spotted best with large binoculars. As part of this huge star forming region, look for the obscuring dark dust cloud Lynds 935 to help you distinguish the nebula’s edges. Although it is every bit as close as the Orion Nebula, this star hatchery isn’t quite as easy!

I’m wondering if there has been or ever will be a full moon on a Tuesday, specifically September 16th? Any year.