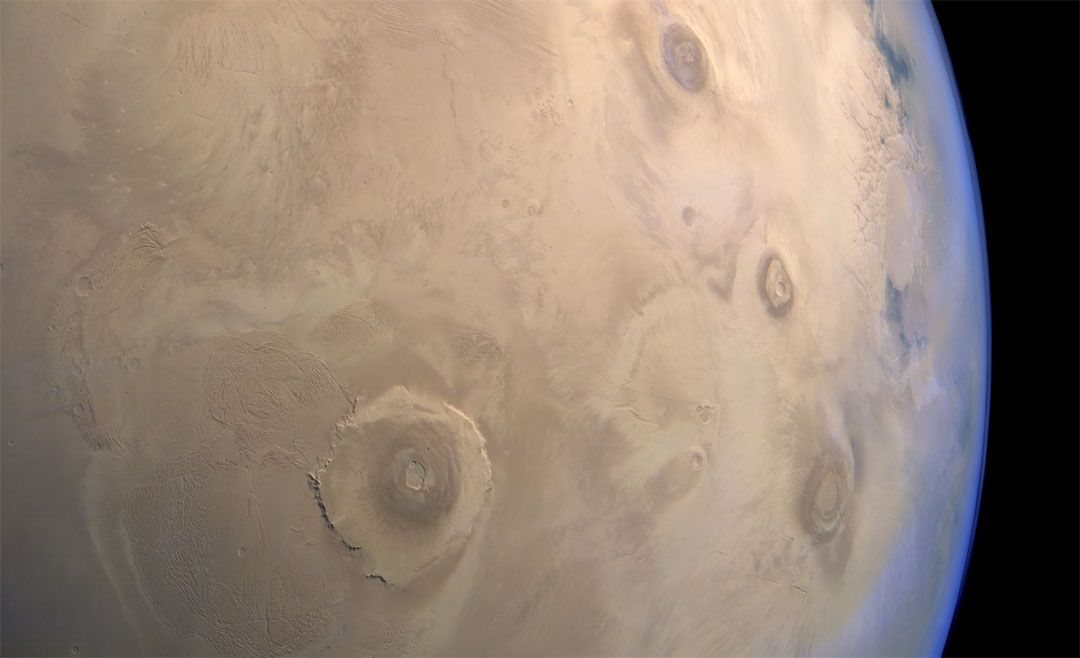

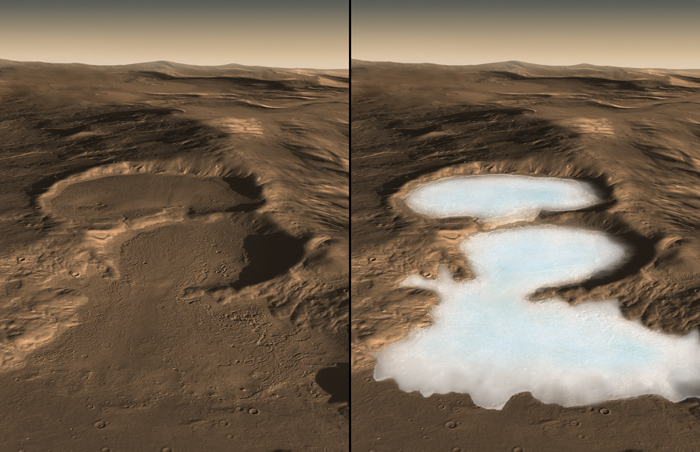

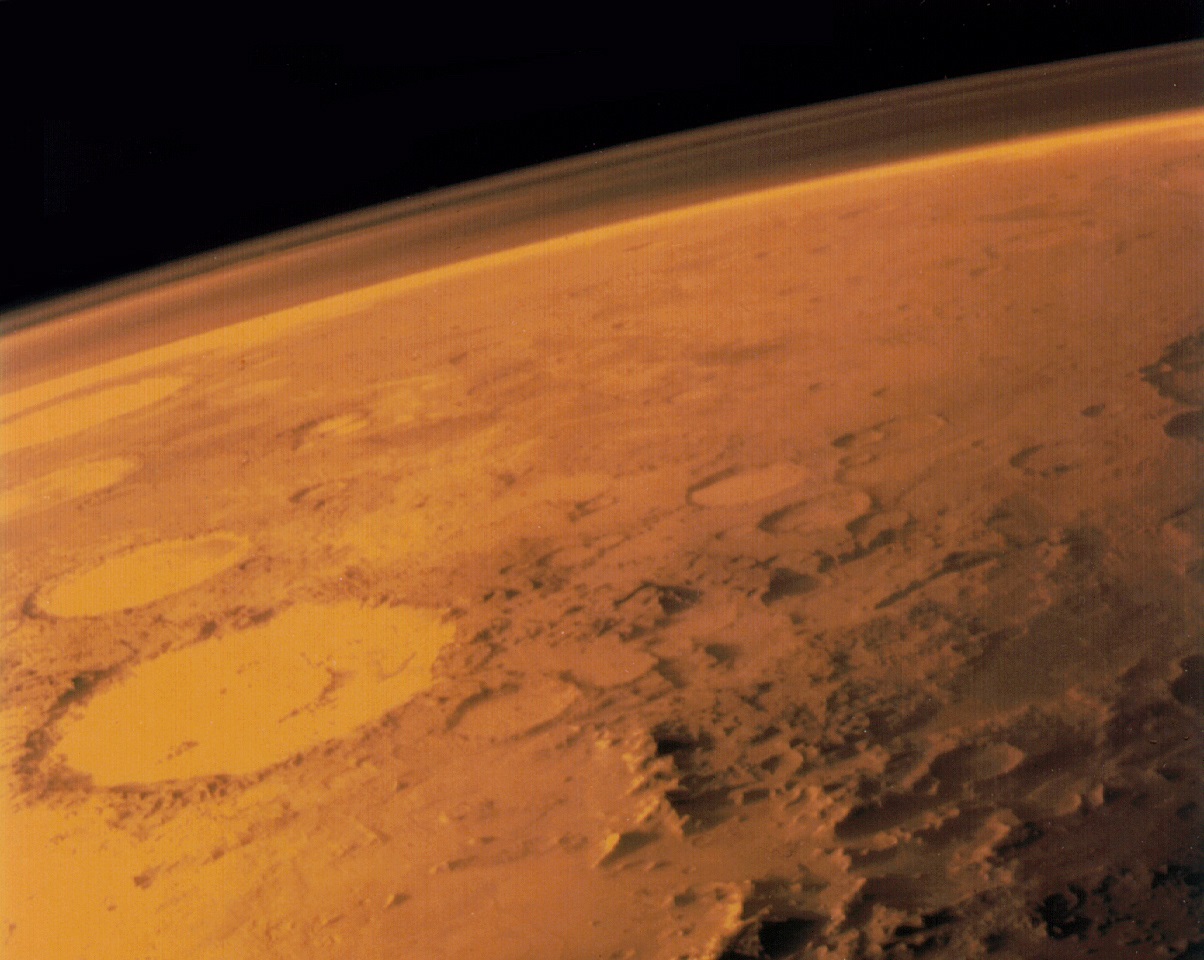

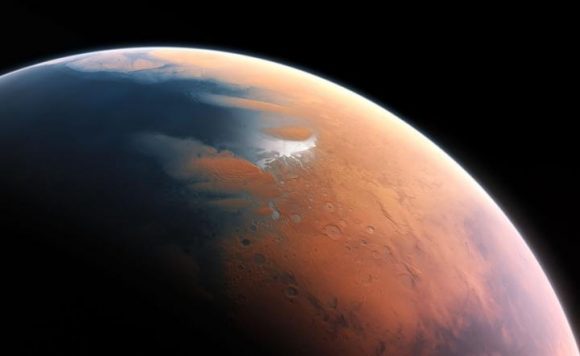

Thanks to the many missions that have been studying Mars in recent years, scientists are aware that roughly 4 billion years ago, the planet was a much different place. In addition to having a denser atmosphere, Mars was also a warmer and wetter place, with liquid water covering much of the planet’s surface. Unfortunately, as Mars lost its atmosphere over the course of hundreds of millions of years, these oceans gradually disappeared.

When and where these oceans formed has been the subject of much scientific inquiry and debate. According to a new study by a team of researchers from UC Berkeley, the existence of these oceans was linked to the rise of the Tharis volcanic system. They further theorize that these oceans formed several hundred millions years earlier than expected and were not as deep as previously thought.

The study, titled “Timing of oceans on Mars from shoreline deformation“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Nature. The study was conducted by Robert I. Citron, Michael Manga and Douglas J. Hemingway – a grad student, professor and post doctoral research fellow from the Department of Earth and Planetary Science and the Center for Integrative Planetary Science at UC Berkeley (respectively).

As Michael Manga explained in a recent Berkeley News press release:

“The assumption was that Tharsis formed quickly and early, rather than gradually, and that the oceans came later. We’re saying that the oceans predate and accompany the lava outpourings that made Tharsis.”

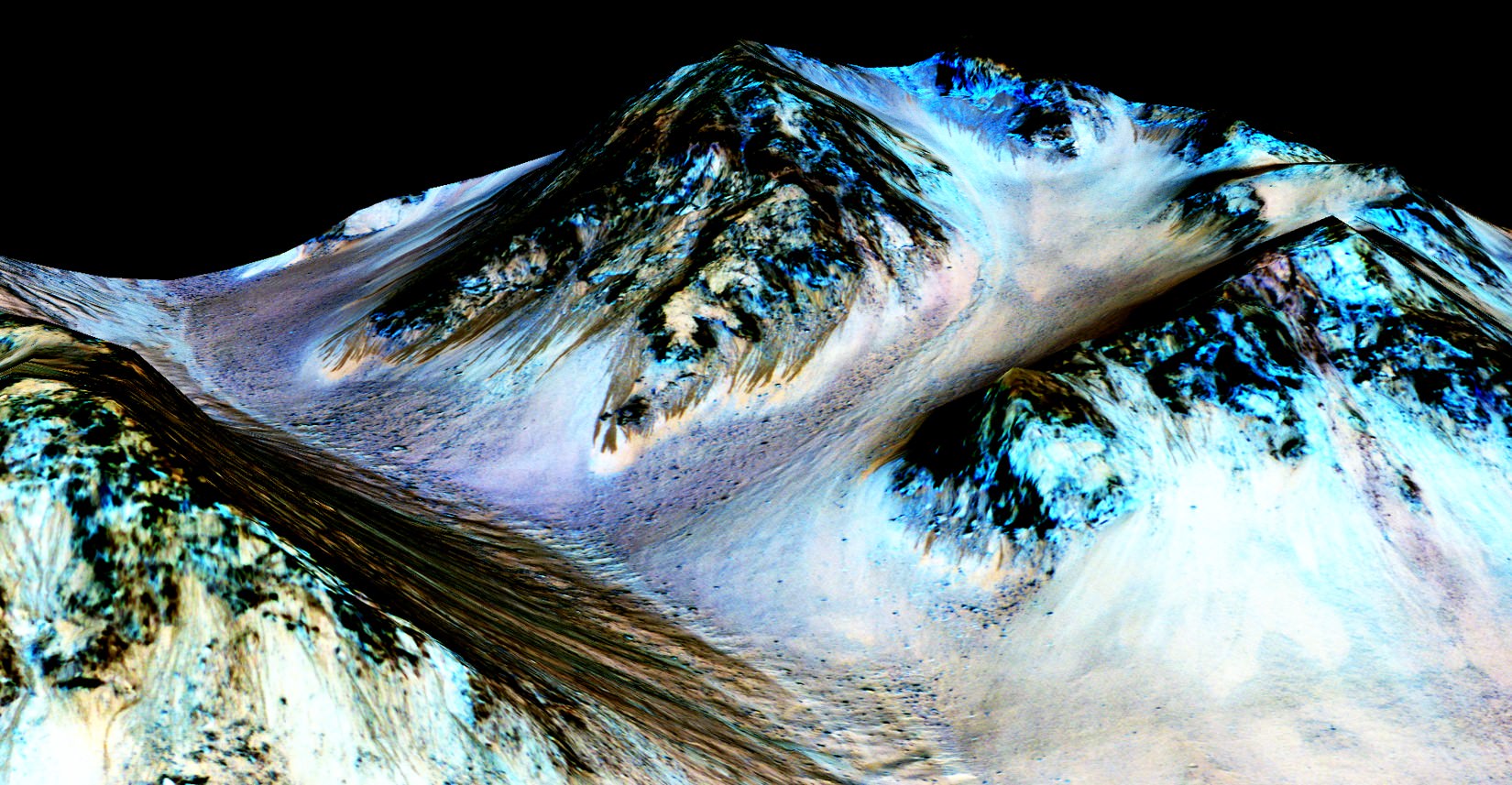

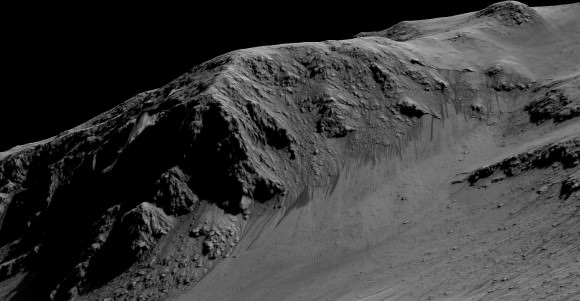

The debate over the size and extent of Mars’ past oceans is due to some inconsistencies that have been observed. Essentially, when Mars lost its atmosphere, its surface water would have frozen to become underground permafrost or escaped into space. Those scientists who don’t believe Mars once had oceans point to the fact that the estimates of how much water could have been hidden away or lost is not consistent with estimates on the oceans’ sizes.

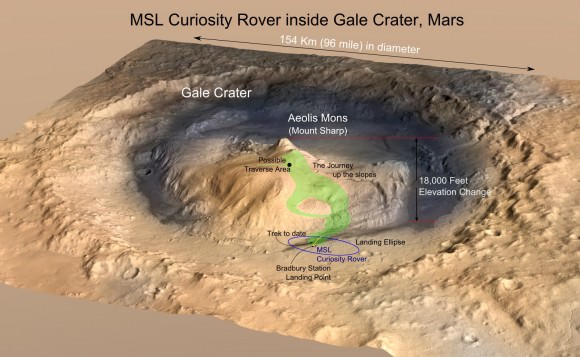

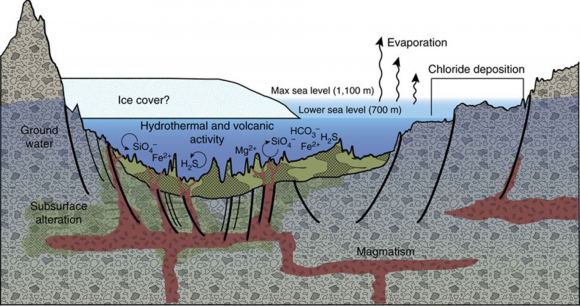

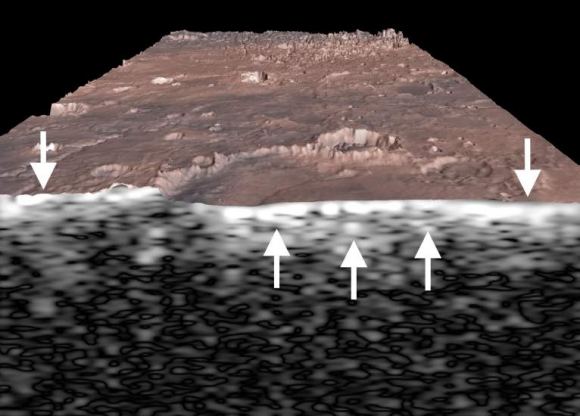

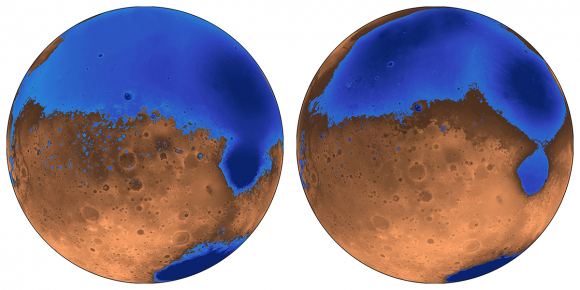

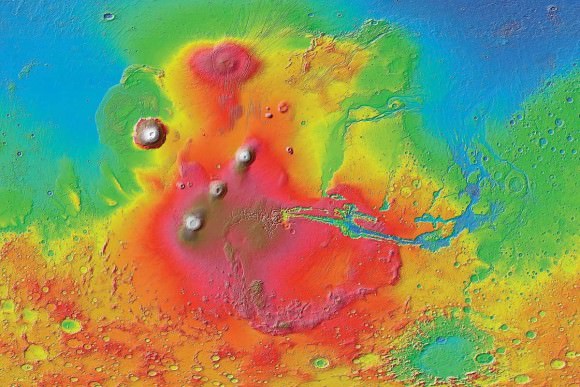

What’s more, the ice that is now concentrated in the polar caps is not enough to create an ocean. This means that either less water was present on Mars than previous estimates indicate, or that some other process was responsible for water loss. To resolve this, Citron and his colleagues created a new model of Mars where the oceans formed before or at the same time as Mars’ largest volcanic feature – Tharsis Montes, roughly 3.7 billion years ago.

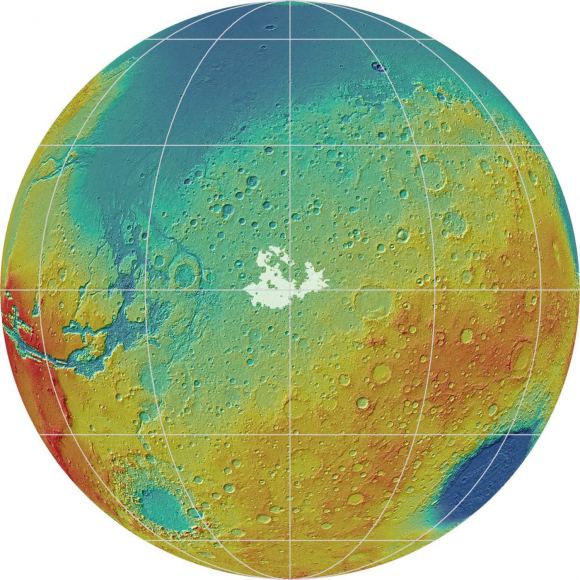

Since Tharsis was smaller at the time, it did not cause the same level of crustal deformation that it did later. This would have been especially true of the plains that cover most the northern hemisphere and are believed to have been an ancient seabed. Given that this region was not subject to the same geological change that would have come later, it would have been shallower and held about half the water.

“The assumption was that Tharsis formed quickly and early, rather than gradually, and that the oceans came later,” said Manga. “We’re saying that the oceans predate and accompany the lava outpourings that made Tharsis.”

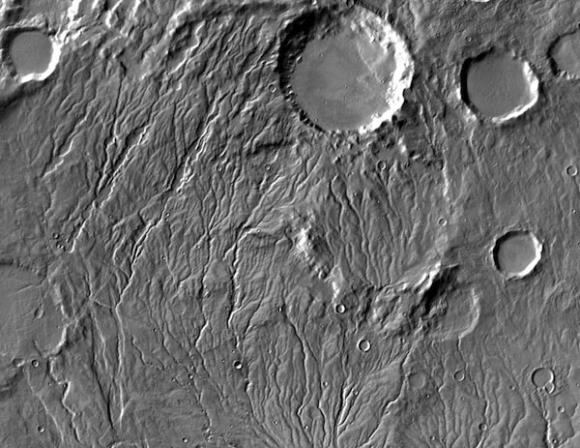

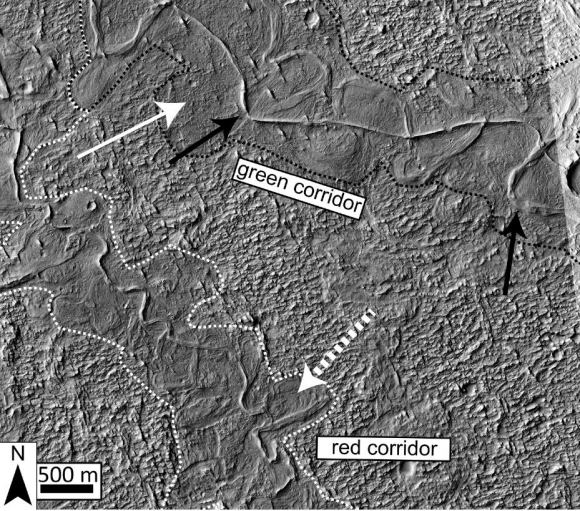

In addition, the team also theorized that the volcanic activity that created Tharsis may have been responsible for the formation of Mars’ early oceans. Basically, the volcanoes would have spewed gases and volcanic ash into the atmosphere that would have led to a greenhouse effect. This would have warmed the surface to the point that liquid water could form, and also created underground channels that allowed water to reach the northern plains.

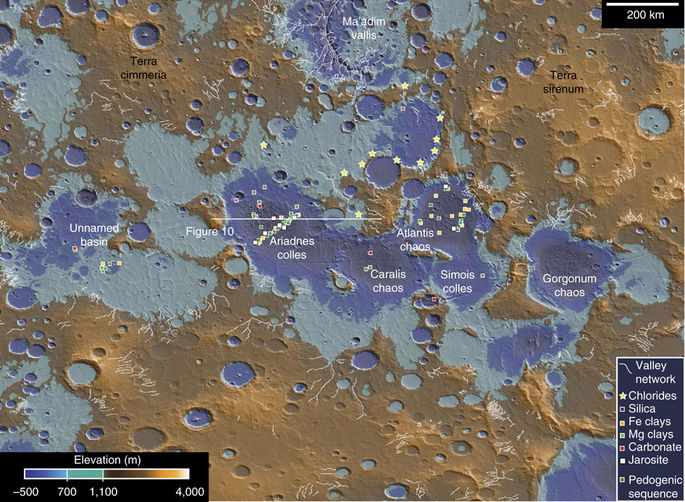

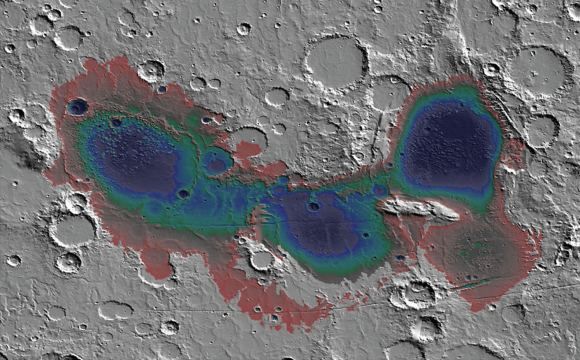

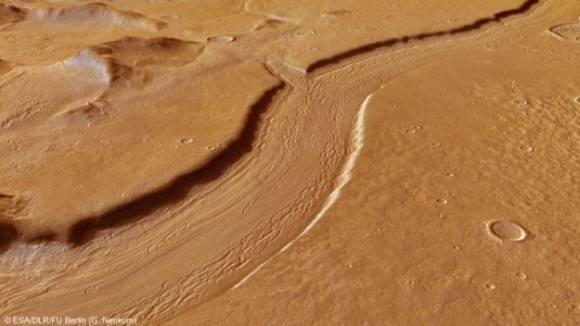

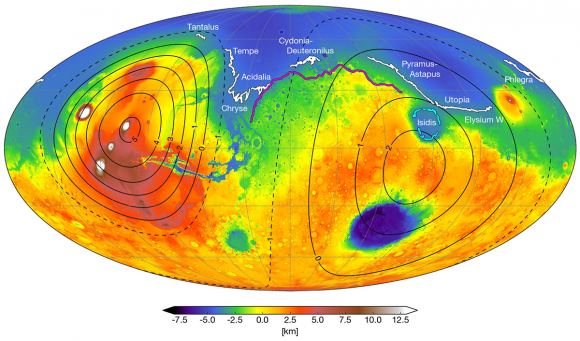

Their model also counters other previous assumptions about Mars, which are that its proposed shorelines are very irregular. Essentially, what is assumed to have been “water front” property on ancient Mars varies in height by as much as a kilometer; whereas on Earth, shorelines are level. This too can be explained by the growth of the Tharsis volcanic region, roughly 3.7 billion years ago.

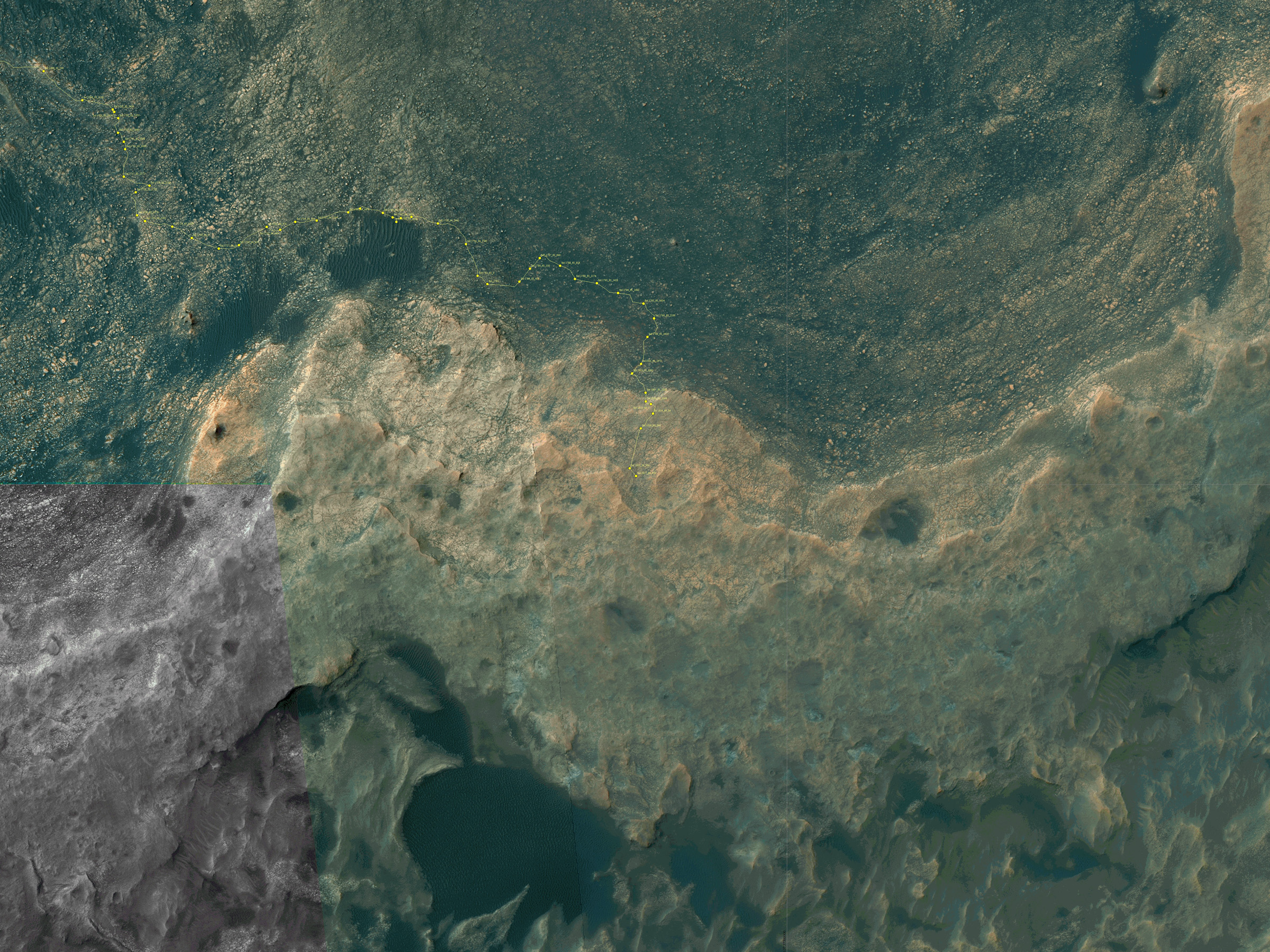

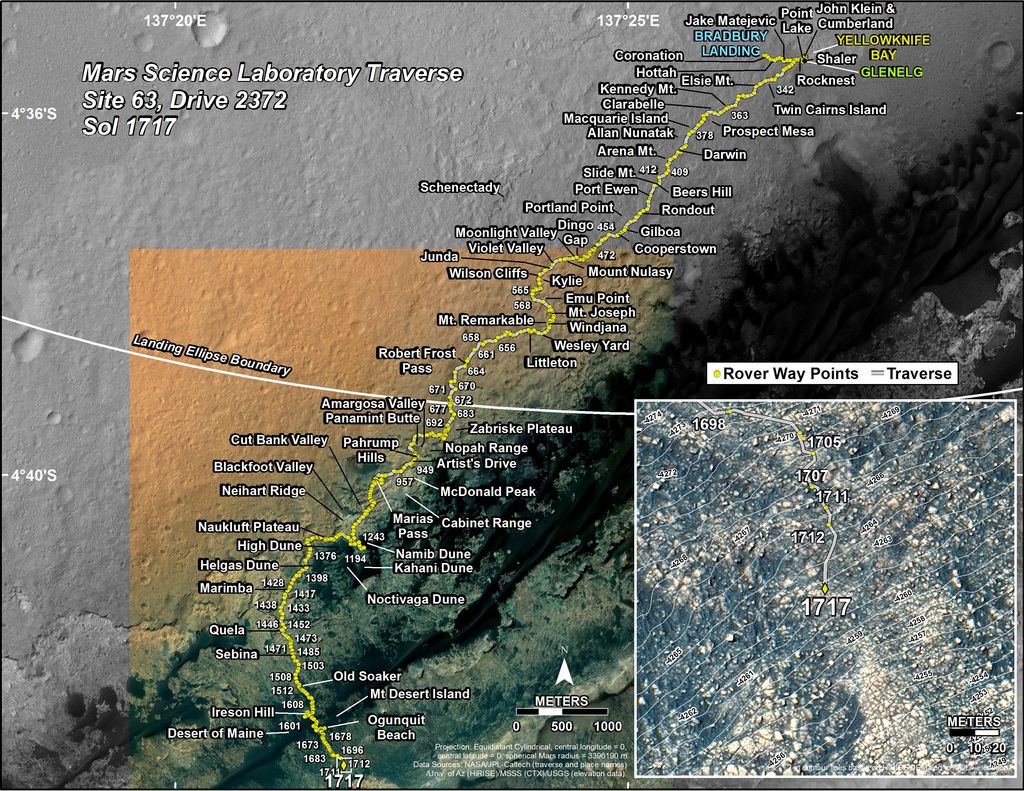

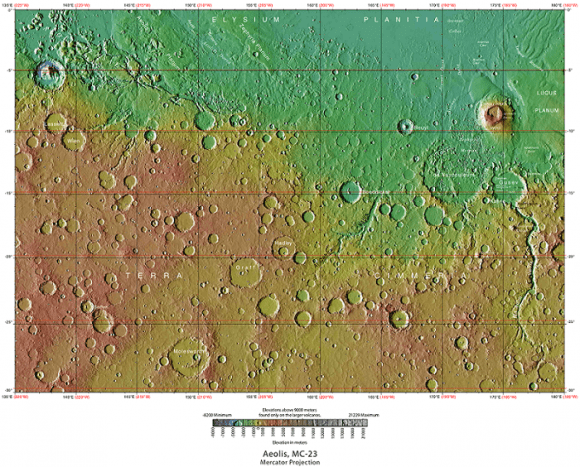

Using current geological data of Mars, the team was able to trace how the irregularities we see today could have formed over time. This would have began when Mars first ocean (Arabia) started forming 4 billion years ago and was around to witness the first 20% of Tharsis Montes growth. As the volcanoes grew, the land became depressed and the shoreline shifted over time.

Similarly, the irregular shorelines of a subsequent ocean (Deuteronilus) can be explained by this model by indicating that it formed during the last 17% of Tharsis’ growth – roughly 3.6 billion years ago. The Isidis feature, which appears to be an ancient lakebed slightly removed from the Utopia shoreline, could also be explained this way. As the ground deformed, Isidis ceased being part of the northern ocean and became a connected lakebed.

“These shorelines could have been emplaced by a large body of liquid water that existed before and during the emplacement of Tharsis, instead of afterwards,” said Citron. This is certainly consistent with the observable effect that Tharsis Mons has had on the topography of Mars. It’s bulk not only creates a bulge on the opposite side of the planet (the Elysium volcanic complex), but a massive canyon system in between (Valles Marineris).

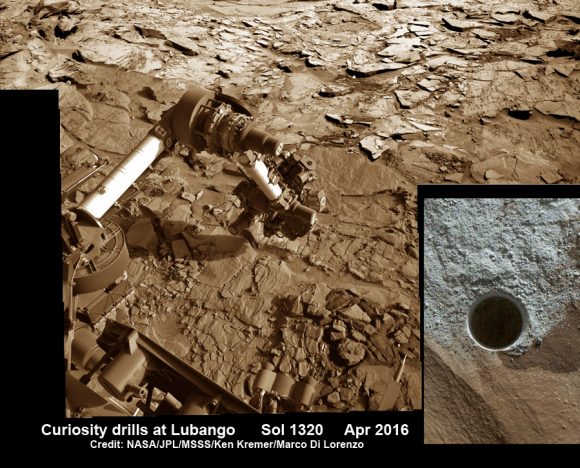

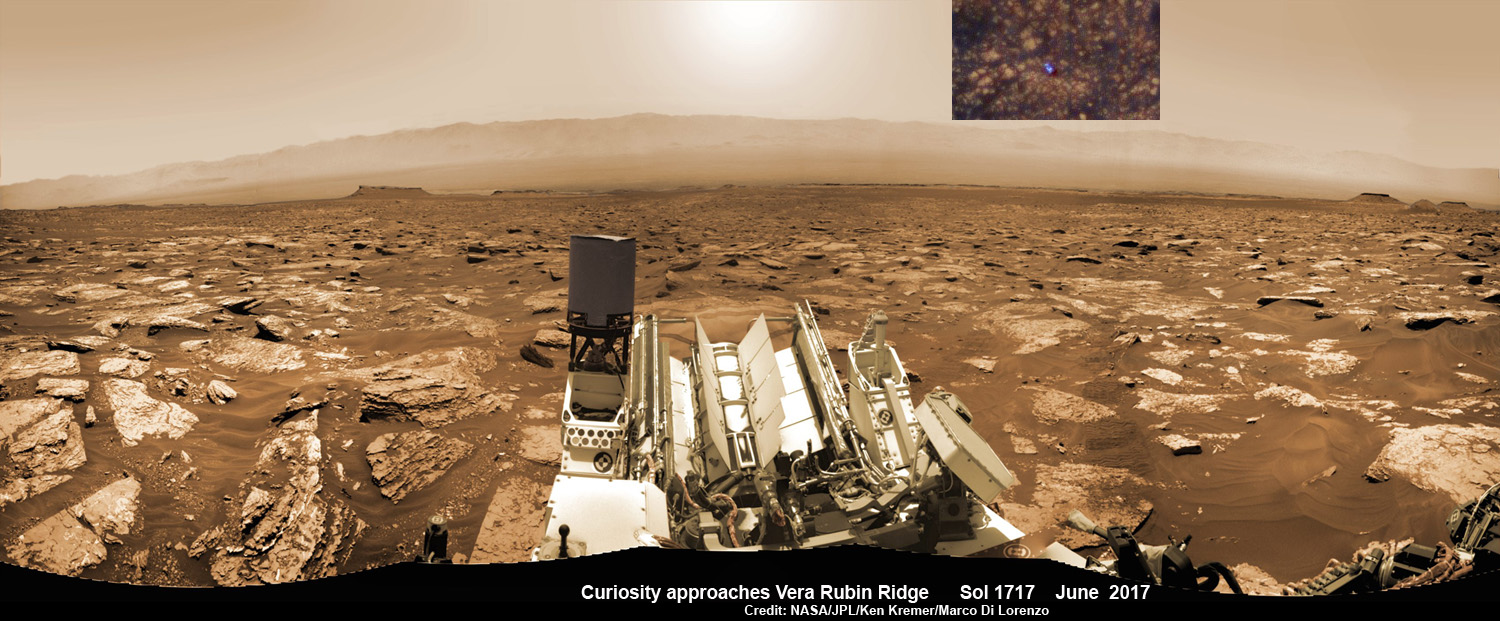

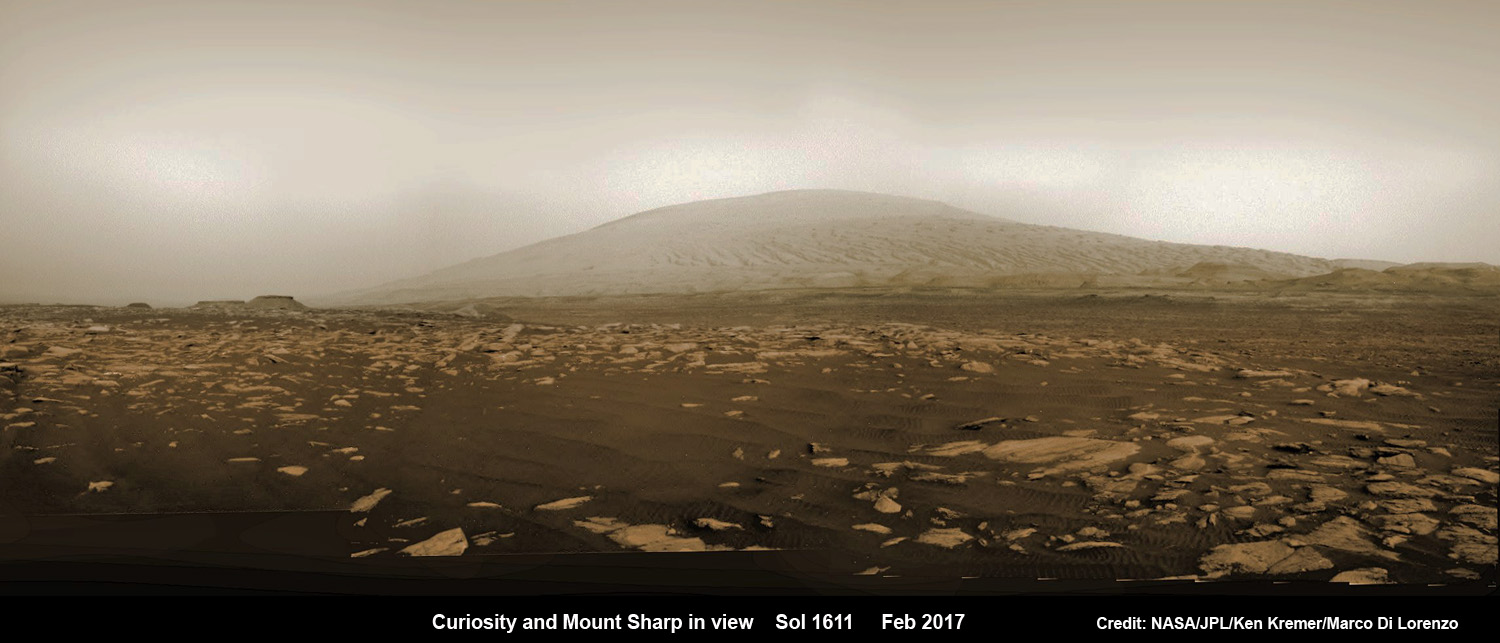

This new theory not only explains why previous estimates about the volume of water in the northern plains were inaccurate, it can also account for the valley networks (cut by flowing water) that appeared around the same time. And in the coming years, this theory can be tested by the robotic missions NASA and other space agencies are sending to Mars.

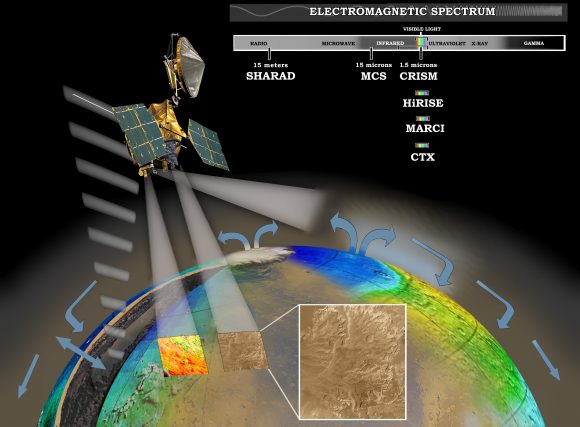

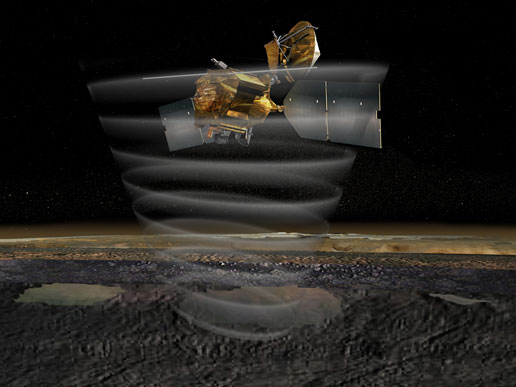

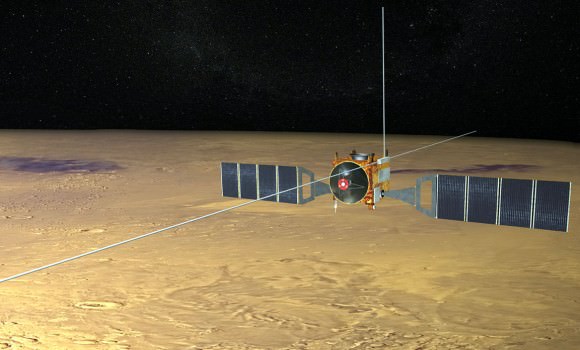

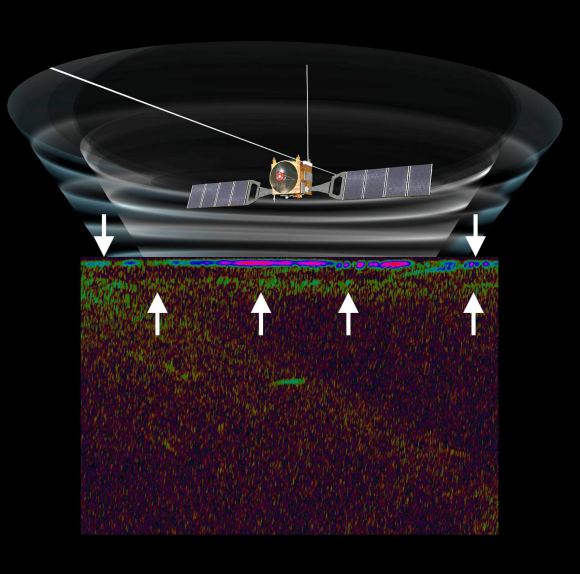

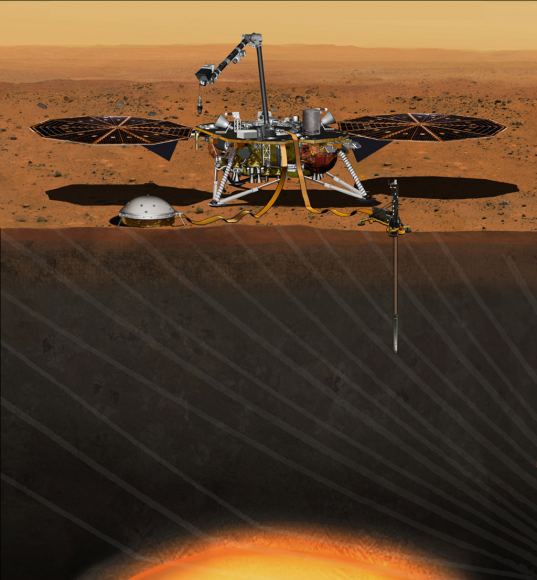

Consider NASA’s Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) mission, which is scheduled for launch in May, 2018. Once it reaches Mars, this lander will use a suite of advanced instruments – which includes a seismometer, temperature probe and radio science instrument – to measure Mars interior and learn more about its geological activity and history.

Among other things, NASA anticipates that InSight might detect the remains of Mars’ ancient ocean frozen in the interior, and possibly even liquid water. Alongside the Mars 2020 rover, the ExoMars 2020, and eventual crewed missions, these efforts are expected to provide a more complete picture of Mars past, which will include when major geological events took place and how this could have affected the planet’s ocean and shorelines.

The more we learn about what happened on Mars over the past 4 billion years, the more we learn about the forces that shaped our Solar System. These studies also go a long way towards helping scientists determine how and where life-bearing conditions can form. This (we hope) will help us locate life it in another star system someday!

The team’s findings were also the subject of a paper that was presented this week at the 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

Further News: Berkeley News, Nature