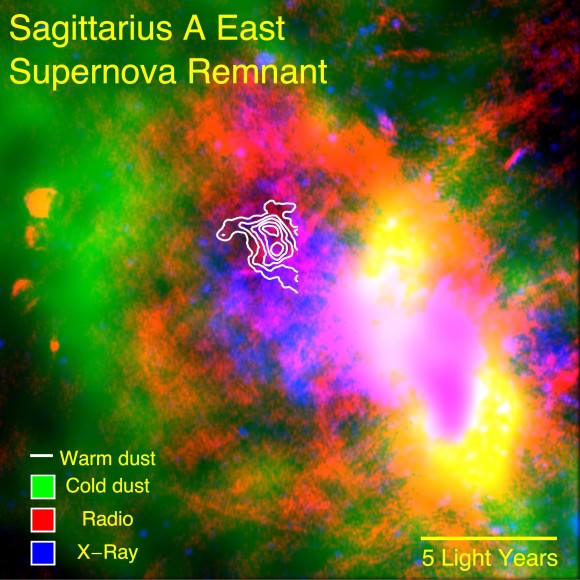

“Life exists because of supernovae,” said Steve Howell, project scientist for NASA’s Kepler and K2 missions at NASA’s Ames Research Center. “All heavy elements in the universe come from supernova explosions. For example, all the silver, nickel, and copper in the earth and even in our bodies came from the explosive death throes of stars.”

So a glimpse of a supernova explosion is of intense interest to astronomers. It’s a chance to study the creation and dispersal of the life-enabling elements themselves. A greater understanding of supernovae will lead to a greater understanding of the origins of life.

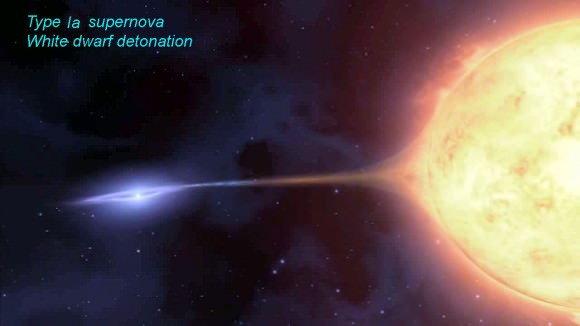

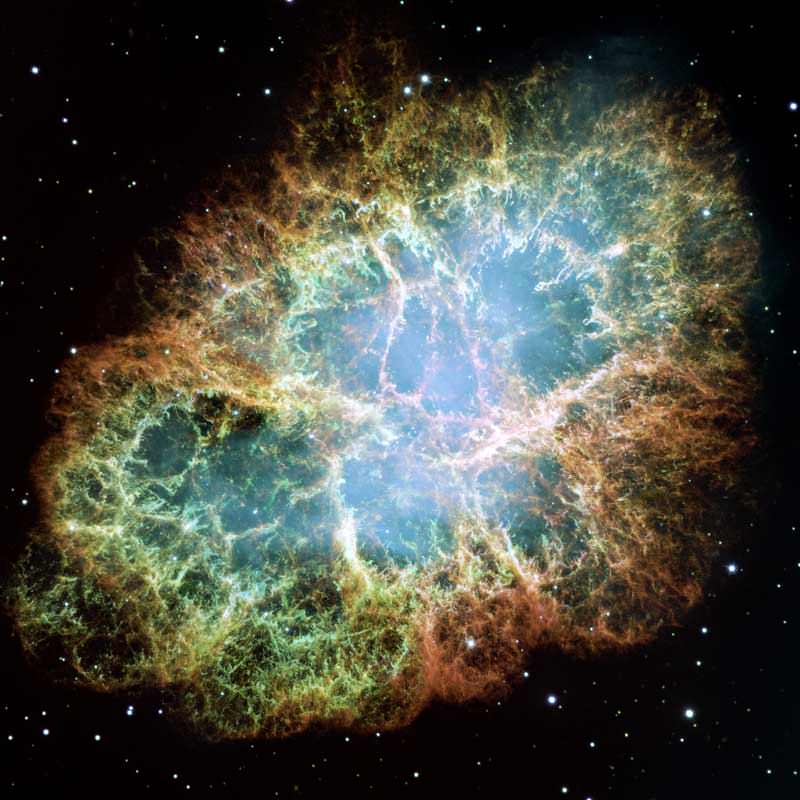

Stars are balancing acts. They are a struggle between the pressure to expand, created by the fusion in the star, and the gravitational urge to collapse, caused by their own enormous mass. When the core of a star runs out of fuel, the star collapses in on itself. Then there is a massive explosion, which we call a supernova. And only very large stars can become supernovae.

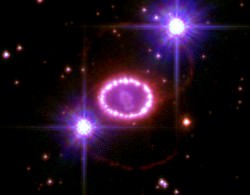

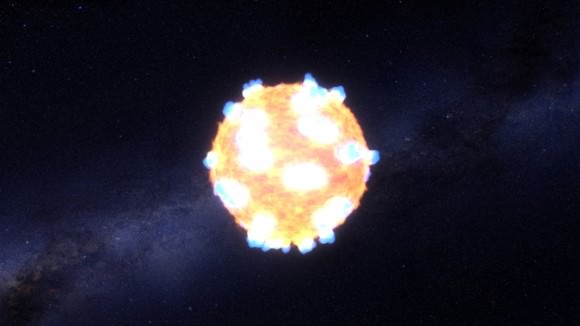

The brilliant flashes that accompany supernovae are called shock breakouts. These events last only about 20 minutes, an infinitesimal amount of time for an object that can shine for billions of years. But when Kepler captured two of these events in 2011, it was more than just luck.

Peter Garnavich is an astrophysics professor at the University of Notre Dame. He led an international team that analyzed the light from 500 galaxies, captured every 30 minutes over a period of 3 years by Kepler. They searched about 50 trillion stars, trying to catch one as it died as a supernova. Only a fraction of stars are large enough to explode as supernovae, so the team had their work cut out for them.

“In order to see something that happens on timescales of minutes, like a shock breakout, you want to have a camera continuously monitoring the sky,” said Garnavich. “You don’t know when a supernova is going to go off, and Kepler’s vigilance allowed us to be a witness as the explosion began.”

In 2011 Kepler caught two gigantic stars as they died their supernova death. Called KSN 2011a, and KSN 2011d, the two red super-giants were 300 times and 500 times the size of our Sun respectively. 2011a was 700 million light years from Earth, and 2011d was 1.2 billion light years away.

The intriguing part of the two supernovae is the difference between them; one had a visible shock breakout and one did not. This was puzzling, since in other respects, both supernovae behaved much like theory predicted they would. The team thinks that the smaller of the two, KSN 2011a, may have been surrounded by enough gas to mask the shock breakout.

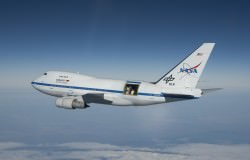

The Kepler spacecraft is well-known for searching for and discovering extrasolar planets. But when some components on board Kepler failed in 2013, the mission was re-cast as the K2 Mission. “While Kepler cracked the door open on observing the development of these spectacular events, K2 will push it wide open, observing dozens more supernovae,” said Tom Barclay, senior research scientist and director of the Kepler and K2 guest observer office at Ames. “These results are a tantalizing preamble to what’s to come from K2!”

(For a brilliant and detailed look at the life-cycle of stars, I recommend “The Life and Death of Stars” by Kenneth R. Lang.)