Author’s note: In the wake of the November 13th terrorist attacks, the French Space Agency CNES canceled the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the launch of Asterix. This post commemorates the launch of France’s first satellite 50 years ago this week, and pays a small tribute to the noblest of human endeavors, namely the exploration of space and the pioneering spirit of humanity exemplified by a heroic nation.

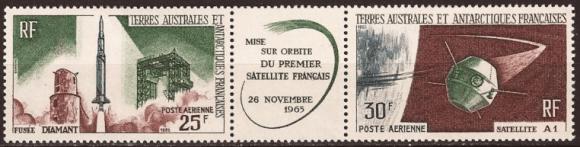

A milestone in space flight occurred 50 years ago tomorrow, when France became the sixth nation—behind the U.S.S.R., the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom and Italy—to field a satellite. The A1 mission, renamed Asterix after a popular cartoon character, launched from a remote desert base in Algeria a few hours after dawn at 9:52 UT on November 26th.

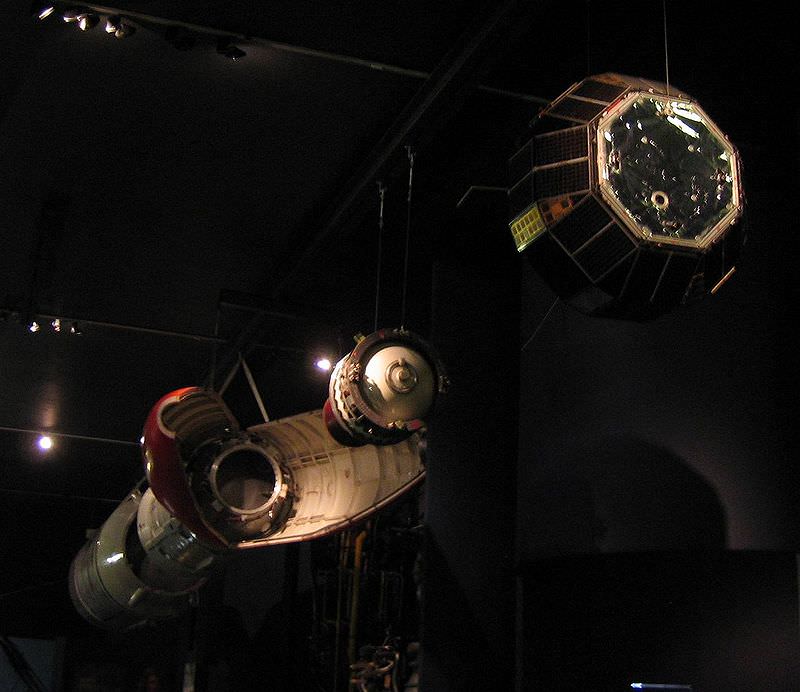

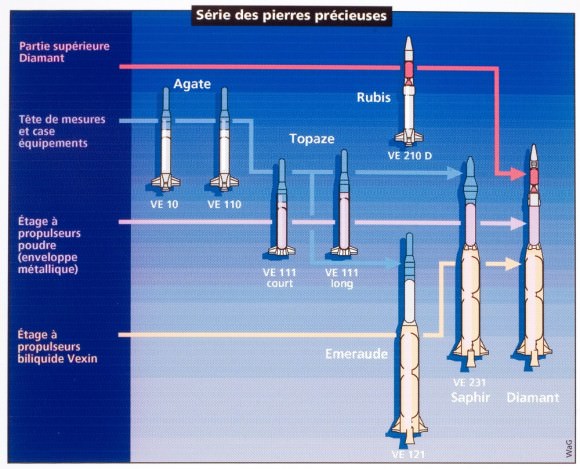

Though France was 6th nation in space, it was 3rd—following the Soviet Union and the United States—to launch a satellite atop its very own rocket: the three stage Diamant-A.

The satellite launch was intended mainly to test the ability of the French-built rocket, which flew 11 more times before its retirement in 1975. Asterix did carry a signal transmitter, and was due to carry out ionospheric measurements during its short battery-powered life span. With a high elliptical orbit, Asterix won’t reenter the Earth’s atmosphere for several centuries to come.

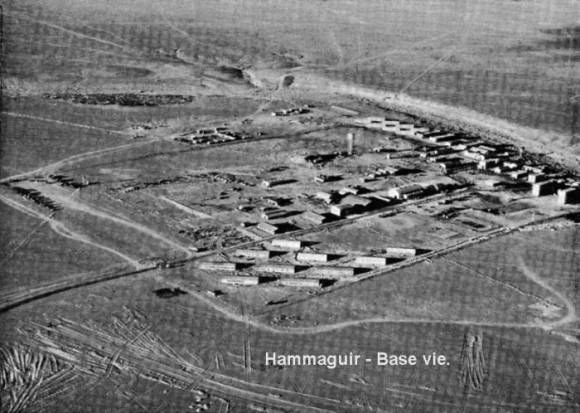

The launch occurred from the remote desert air base of Hammaguir, located 31 degrees north of the equator in western Algeria. Then as today, the site is a forlorn and austere location with very few creature comforts, though we can personally attest from our deployment to a similar French Air Base in Djibouti that the French military does serve wine in their mess hall…

The French space program started in 1961 under president Charles de Gaulle and centered around the construction and use of the Diamant rocket. Three variants were built, including the one used to place Asterix in orbit. One of the stranger tales of the early space age involved the first—and thus far only—sub-orbital launch of a cat into space from the same Algerian site in 1963, though Iran recently made a vague statement that it would do the same in 2013.

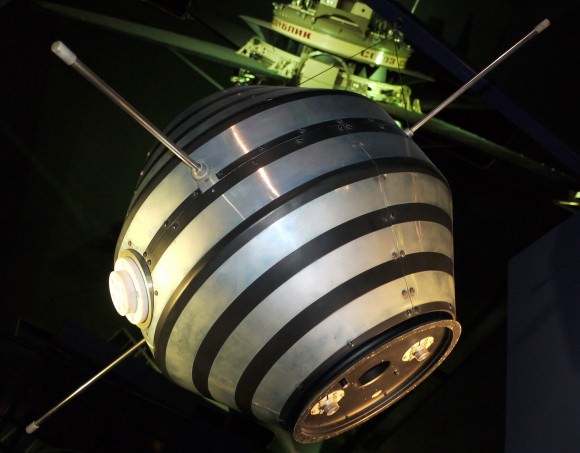

Contact with Asterix was lost due to a damaged satellite antenna shortly after launch. Founded in 1961, the French space agency CNES (The Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales, or National Centre for Space Studies) now partners with NASA and the European Space Agency on missions including micro-gravity studies on the International Space Station, Rosetta’s historic exploration of comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko and more. And although the Hammaguir space facility in Algeria is no longer in use, CNES operates out of the Kourou Space Center in French Guiana and the Toulouse Space Center in southern France today.

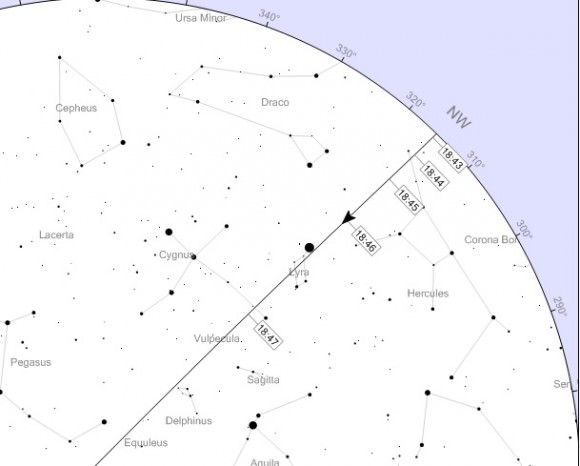

Tracking Asterix

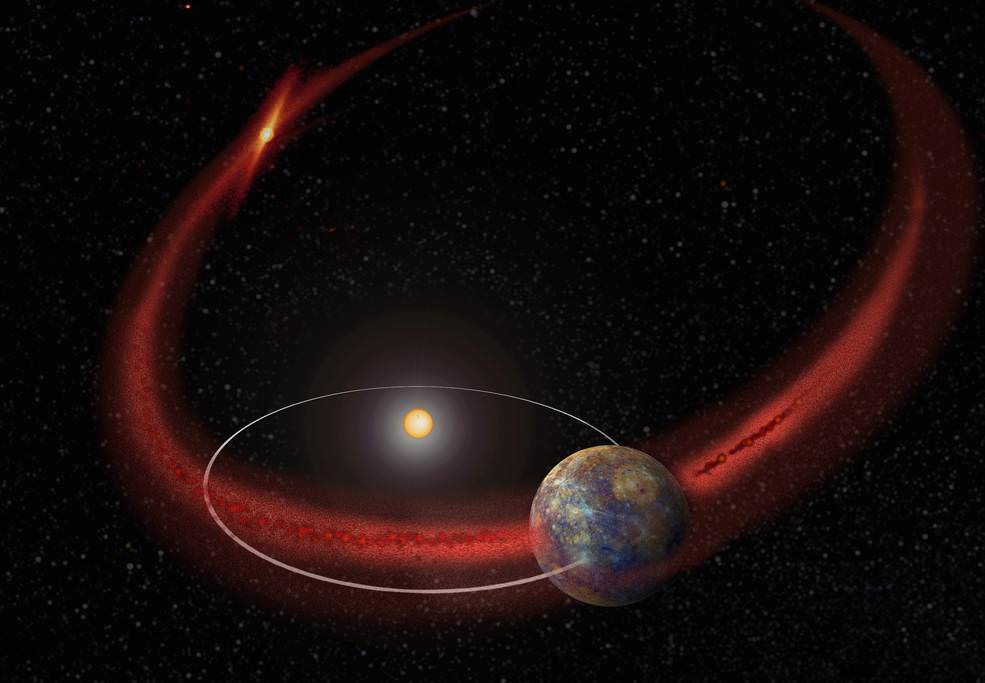

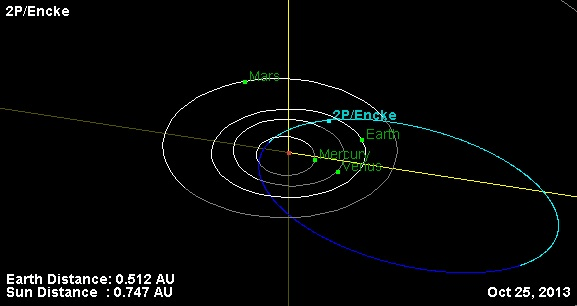

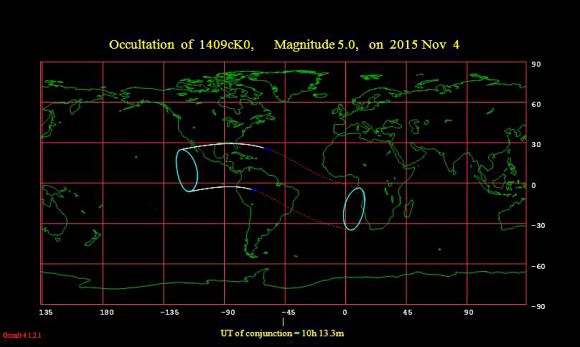

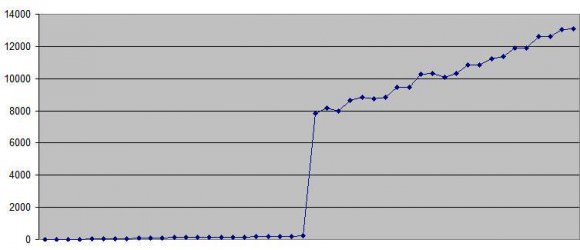

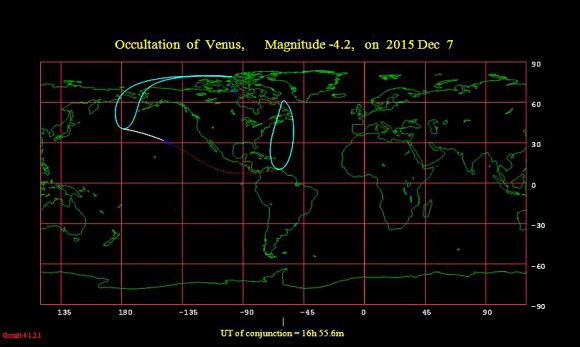

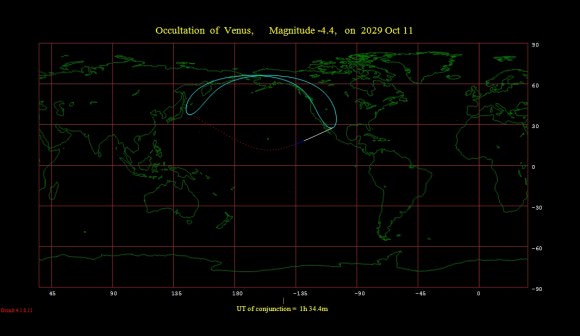

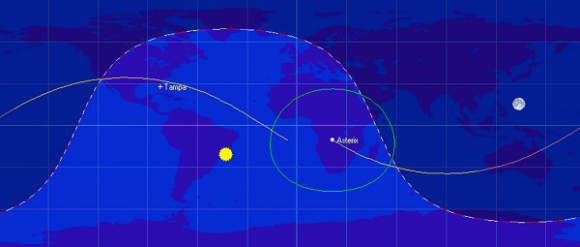

Though inoperative, Asterix still orbits the Earth once every 107 minutes in an elliptical low Earth orbit. Asterix ranges from a perigee of 523 kilometers to an apogee of 1,697 kilometers. In an orbit inclined 34 degrees relative to the Earth’s equator, Asterix isn’t expected to reenter for several centuries.

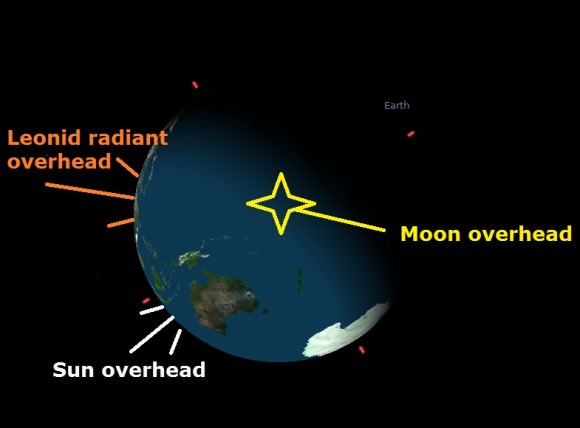

A 42 kilogram satellite approximately a meter across, Asterix is visible worldwide from about 40 degrees north to 40 degrees south latitude. Essentially a binocular object, you can nonetheless see Asterix from your backyard if you know exactly where and when to look for it in the sky. Asterix will appear brightest on a perigee pass directly overhead.

Asterix’s NORAD ID satellite catalog number is 01778/COSPAR ID 1965-096A.

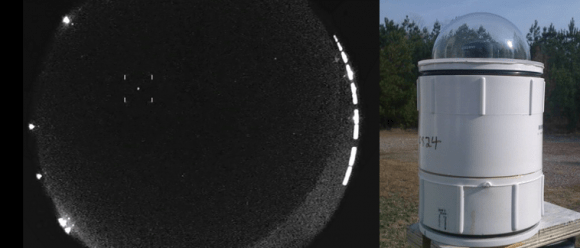

When it comes to hunting for binocular satellites, you need to now exactly where it’ll be in the sky at what time. We use Heavens-Above to discern exactly when a given satellite will pass a bright star, then simply watch at the appointed time with binoculars. We also run WWV radio in the background for a precise audio time hack. This allows us to keep our eyes continuously on the sky. This simple method is similar to that used by Project Moonwatch volunteers to track and record satellites starting in the late 1950s.

Other satellite challenges from the early Space Age include Alouette-1 (Canada’s first satellite), Prospero (UK’s first and only indigenous satellite) and the oldest of them all, the first three Vanguard satellites launched by the United States.

Don’t miss a chance to see this living relic of the early space age, still in orbit. Happy 50th to the CNES space agency: may your spirit of space exploration continue to soar and inspire us all.