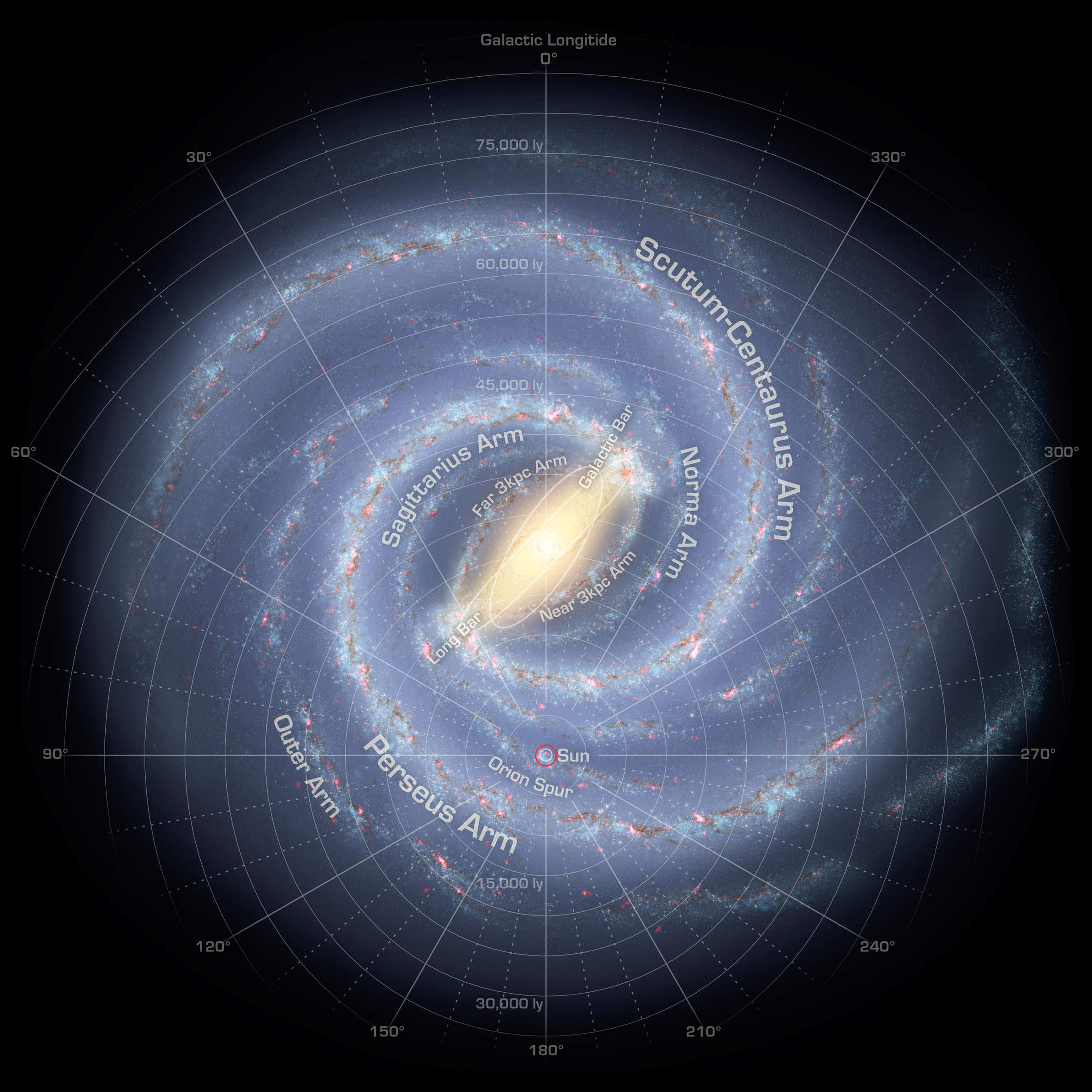

We live in a galaxy that is called the Milky Way. It’s called a barred spiral galaxy, which means that it has a spiral shape with a bar of stars across its middle. The galaxy is rather huge — at least 100,000 light-years in diameter, making it the second-biggest in our Local Group of galaxies.

More mind-blowing is that this mass of stars, gas, planets and other objects are all spinning. Just like a pinwheel. It’s spinning at 270 kilometers per second (168 miles per second) and takes about 200 million years to complete one rotation, according to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. But why? More details below.

It’s worth taking a quick detour to talk about how long it takes the Solar System to move around the center of the galaxy. According to National Geographic, that’s about 225 million years. Dinosaurs were starting to arise the last time we were in the position we are today.

Scientists have mapped the spin using the Very Large Baseline Array, a set of radio telescopes. They examined spots where stars were forming and paid particular attention to those areas where gas molecules enhance radio emission, according to the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Dubbed “cosmic masers”, these areas shine brightly in radio waves.

As Earth moves in its orbit, the shift of these molecules can be mapped against more distant objects. Measuring this shift shows how the entire galaxy rotates — and can even provide information about the mass of the Milky Way. So that’s all very neat, but why is it rotating in the first place?

If we think back to the early Universe, there are two big assumptions astronomers make, according to How Stuff Works: there was a lot of hydrogen and helium, with some parts denser than other areas. In the denser areas, gas clumped together in protogalactic clouds; the thickest areas collapsed into stars.

“These stars burned out quickly and became globular clusters, but gravity continued to collapse the clouds,” How Stuff Works wrote. “As the clouds collapsed, they formed rotating disks. The rotating disks attracted more gas and dust with gravity and formed galactic disks. Inside the galactic disk, new stars formed. What remained on the outskirts of the original cloud were globular clusters and the halo composed of gas, dust and dark matter.”

A simpler way to think about this is if you’re creating a pizza by tossing a ball of dough into the air. The spin of the dough creates a flat disc — just like what you observe in more complicated form in the Milky Way, not to mention other galaxies.

For more on the Milky Way, visit the rest of our section here in the Guide to Space or listen to Astronomy Cast: Episode 99.

Perhaps more about how the primordial cloud had a spin overall and all the vortex of different orientations averaged out and the left over either fell towards the center helping an increase in density there and or even being part of the building of the supermassive black hole then probably forming a quasar that was bright enough to push out the in falling gasses to stop the overall growth of the galaxy.

I also wonder if the quasar phase acted like the sun in the solar nebula favoring condensation of some materials farther our vs closer in. Granted that phase is long gone but perhaps a fossil of that age persists.

To start with: the Milky Way does not rotate… it simply does not exist (like a “thing”). What we have here is a bunch of stars n gas n dirt, bound loosely by gravity and each of these “bodies” moves independent from the others. You can kick one out of it.s orbit and the rest…. is almost not affected. It’s not like a big pane of glass – if you stop it on one end…. it stops everywhere at the same time.The German astrophysicists Burkhard & Kippenhahn had a very good description in their 1996 book: “Die Milchstrasse” (The Milky Way)

http://www.amazon.de/Die-Milchstra%C3%9Fe-Andreas-Burkert/dp/3406397174

Unfortunately for non-Germans this book is in German, but since I, amongst some others, have learned a 2nd language… 😉 I’m sure there is an English edition as well.

Page 93 shows “how to create” the spiral arms.

Your definition of a “thing” is a bit simple. Your presence on this forum is virtual, and an agglomeration of diverse signals and textual representations communicated by various protocols. One could as well conclude your post is not in fact a “thing”. Yet it certain is.

That being said, it is true the galaxy doesn’t rotate as a solid object. But then it would be pretty unphysical to propose a solid object a hundred thousand light years across.

I think its all to do with the spin of the massive black hole in the Milky Ways nucleus (like water draining out of a bathtub) 🙂

There has been speculation that dark matter plays a role in making the rotational velocity fairly uniform throughout this galaxy. The really interesting question is why do some galaxies have quite variable rotational velocities with distance from the center, most notably M31?

Got a link for that?

http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/cosmo/lectures/lec17.html

This is straight out of the textbook so to speak. But illustrates the concept of how dark matter in the galactic halo is thought to influence galactic rotational speed.

A mention of conservation of angular momentum might have been helpful with the ‘why’ part.

“These stars burned out quickly and became globular clusters…”

Huh?