If we are indeed stardust, then what will our future hold? And what happened to all that other dust that isn’t in people or planets? These are pretty heady questions perhaps best left for late at night. Since the age of Galileo and perhaps even beforehand these inquisitive night goers have sought an understanding of “What’s out there?” Paul Murdin in his book “Rock Legends – the Asteroids and Their Discoverers” doesn’t answer the big questions directly but he does shed some capricious light upon what the night time reveals and what the future may hold.

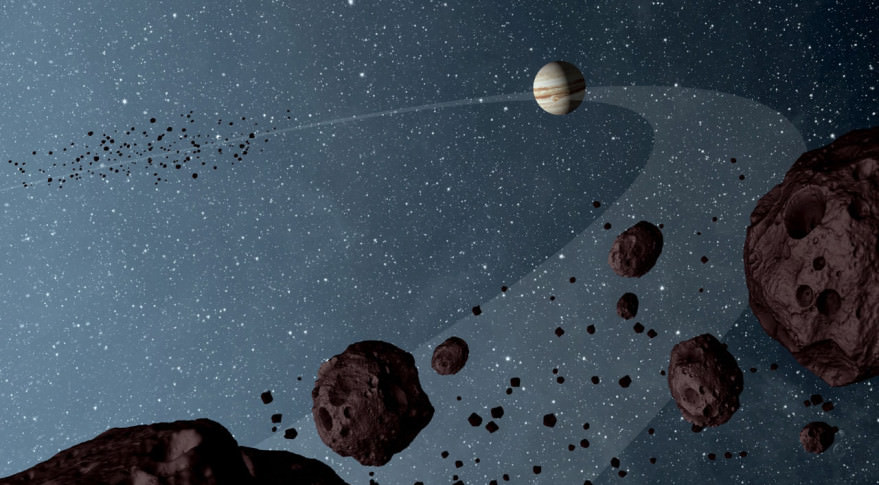

We’re pretty confident that our solar system evolved from a concentration of dust. Let’s leave aside the question about where the dust came from and assume that, at a certain time and place, there was enough free dust that our Sun was made and so too all the planets. In a nice, orderly universe all the dust would have settled out. However, as we’ve discovered since at least the time of Galileo this didn’t happen. There are a plethora of space rocks — asteroids — out wandering through our solar system.

And this is where Murdin’s book steps up. Once people realized that there more than just a few asteroids out there, they took to identifying and classifying them. The book takes a loosely chronological look at this classification and at our increasing knowledge of the orbits, sizes, densities and composition of these space wanderers.

Fortunately this book doesn’t just simply list discovery dates and characteristics. Rather, it includes significant amounts of its contents on the juicy human story that tags along, especially with the naming. It shows that originally these objects were considered special and refined and thus deserved naming with as much aplomb as the planets; i.e. using Greek and Roman deities. Then the number of discovered asteroids outpaced the knowledge of ancient lore, so astronomers began using the names of royalty, friends and eventually pets. Today with well over a million asteroids identified setting a name to an asteroid doesn’t quite have the same lustre, as the author is quick to point out with his own asteroid (128562) Murdin. Yet perhaps there’s not much else to do while waiting for a computer program to identify a few hundred more accumulations of dust, so naming some of the million nameless asteroids could happily fill in some time.

With the identifying of the early asteroid discoverers and the fun names they chose, this part of the book is quite light and simple. It expands the fun by wandering a bit just like the asteroids. From it you learn of the discovery of palladium, the real spelling of Spock’s name and the meaning of YORP. Sometimes the wandering is quite far, as with the origins of the Palladium Theatre, the squabbling surrounding the naming of Ceres and the status of the Cubewanos. Yet it is this capriciousness that gives the book its flavour and makes it great for a budding astronomer or a reference for a generalist. The occasional bouts of reflection on the future of various asteroids and even of the Earth add a little seriousness to an otherwise pleasant prose.

So if you’re wondering about the next occultation of Eris or the real background of the name (3512) Eriepa then you’re into asteroids. And perhaps you’re learning how to survive on a few hours of sleep so you can search for one more faint orbiting mote. Whether that’s the case or you’re just interested in how such odd names came to represent these orbiting rocks then Paul Murdin’s book “Rock Legends – the Asteroids and Their Discoverers” will be a treat. Read it and maybe you can use it to place your own curve upon an asteroid’s name.

The book is available on Springer. Find out more about author Paul Murdin here.