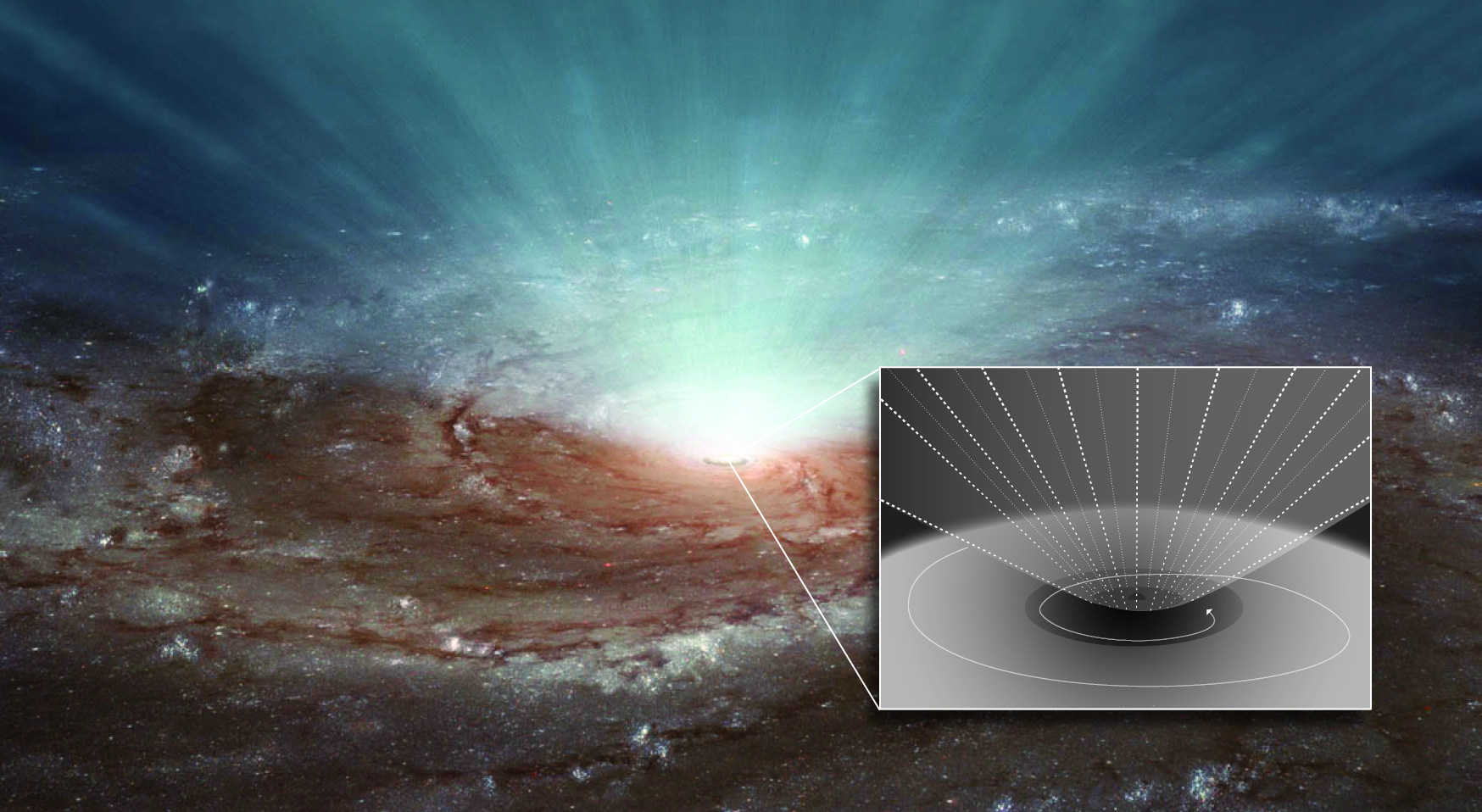

Most galaxies have a super-massive black hole at their centre. As galaxies collide and merge, the black holes merge too, creating the super-massives we see in the universe today. But one team of astronomers went looking for super-massives that aren’t at the heart of galaxies. They looked at over 1200 galaxies, using the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA), and almost all of them had a black hole right where it should be, in the middle of the galaxy itself.

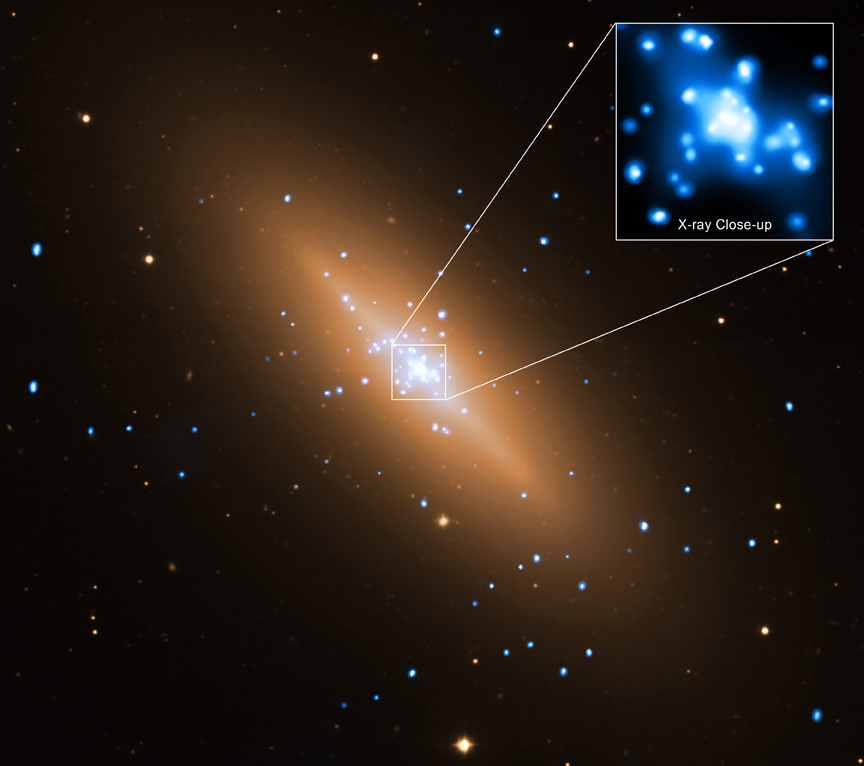

But they did find one hole, in a cluster of galaxies more than two billion light years away from Earth, that was not at the centre of a galaxy. They were surprised too see that this black hole had been stripped naked of surrounding stars. Once they identified this black hole, now called B3 1715+425, they used the Hubble and the Spitzer to follow up. And what they found tells an unusual story.

“We’ve not seen anything like this before.” – James Condon

The super-massive black hole in question, which we’ll call B3 for short, was a curiosity. It was far brighter than anything near it, and it was also more distant than most of the holes they were studying. But a black hole this bright is typically situated at the heart of a large galaxy. B3 had only a remnant of a galaxy surrounding it. It was naked.

James Condon, of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) described what happened.

“We were looking for orbiting pairs of supermassive black holes, with one offset from the center of a galaxy, as telltale evidence of a previous galaxy merger,” said Condon. “Instead, we found this black hole fleeing from the larger galaxy and leaving a trail of debris behind it,” he added.

“We concluded that our fleeing black hole was incapable of attracting that many stars on the way out to make it look like it does now.” – James Condon

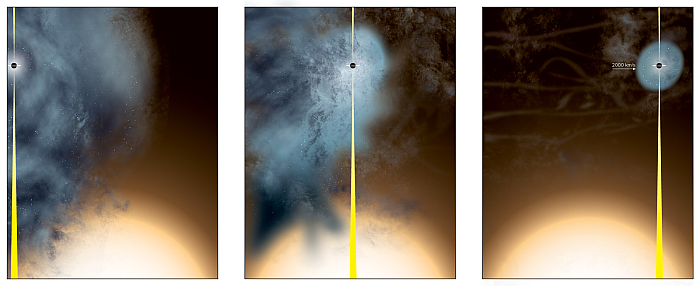

Condon and his team concluded that B3 was once a super-massive black hole at the heart of a large galaxy. B3 collided with another, larger galaxy, one with an even larger black hole. During this collision B3 had most of its stars stripped away, except for the ones closest to it. B3 is still speeding away, at more than 2000 km per second.

Nearly Naked Black Hole from NRAO Outreach on Vimeo.

B3 and what’s left of its stars will continue to move through space, escaping their encounter with the other galaxy. It probably won’t escape from the cluster of galaxies it’s in though.

“What happens to a galaxy when most of its stars have been stripped away, but it still has an active super-massive black hole at the middle?” – James Condon

Condon outlines the likely end for B3. It won’t have enough stars and gas surrounding it to trigger new star birth. It also won’t be able to attract new stars. So eventually, the remnant stars of B3’s original galaxy will travel with it, growing progressively dimmer over time.

B3 itself will also grow dimmer, since it has no new material to “feed” on. It will eventually be nearly impossible to see. Only its gravitational effect will betray its position.

“In a billion years or so, it probably will be invisible.” – James Condon

How many B3s are there? If B3 itself will eventually become invisible, how many other super-massive black holes like it are there, undetectable by our instruments? How often does it happen? And how important is it in understanding the evolution of galaxies, and of clusters of galaxies. Condon asks these questions near the end of the clip. For now, at least, we have no answers.

Condon and his team used the NRAO‘s VLBA to search for these lonely holes. The VLBA is a radio astronomy instrument made up of 10 identical 25m antennae around the world, and controlled at a center in New Mexico. The array provides super sharp detail in the radio wave part of the spectrum.

Their black hole search is a long term project, making use of filler time available at the VLBA. Future telescopes, like the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope being built in Chile, will make Condon’s work easier.

Condon worked with Jeremy Darling of the University of Colorado, Yuri Kovalev of the Astro Space Center of the Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow, and Leonid Petrov of the Astrogeo Center in Falls Church, Virginia. They will report their findings in the Astrophysical Journal.