Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! With very little Moon to contend with this week, it will be a great time to take on some challenging studies like the Helix Nebula, Saturn Nebula, Stephen’s Quintet and more. It’s time to get out your big telescope and head for some dark skies… Because this week isn’t for the beginner! Whenever you’re ready, I’ll see you out back…

Monday, September 10 – Today is the birthday of James E. Keeler. Born in 1857, the American Keeler was a pioneer in the field of spectroscopy and astrophysics. In 1895, Keeler proved that different areas in Saturn’s rings rotate at different velocities. This clearly showed that Saturn’s rings were not solid, but were instead a collection of smaller particles in independent orbits.

Now, let’s head on to Capricornus and drop about four finger-widths south of its northeastern most star – Delta – and have a look at M30 (Right Ascension: 21 : 40.4 – Declination: -23 : 11). Discovered in 1764 by Charles Messier, binocular observers will spot this small, but attractive, globular cluster easily in the same field with star 41. For telescopic observers, you will find a dense core region and many chains of resolvable stars in this 40,000 light year distant object. Power up!

Let’s get some more practice in Capricornus, and take on a more challenging target with confidence. Locate the centermost bright star in the northern half of the constellation – Theta – because we’re headed for the “Saturn Nebula”.

Three finger-widths north of Theta you will see dimmer Nu, and only one finger-width west is NGC 7009 (Right Ascension: 21 : 04.2 – Declination: -11 : 22). Nicknamed the “Saturn Nebula”, this wonderful blue planetary is around 8th magnitude and achievable in small scopes and large binoculars. Even at moderate magnification, you will see the elliptical shape which gave rise to its moniker. With larger scopes, those “ring like” projections become even clearer, making this challenging object well worth the hunt. You can do it!

Tuesday, September 11 –Today celebrates the birthday of Sir James Jeans. Born in 1877, English-born Jeans was an astronomical theoretician. During the beginning of the 20th century, Jeans worked out the fundamentals of the process of gravitational collapse. This was an important contribution to the understanding of the formation of solar systems, stars, and galaxies.

So, are we ready to try for the “Helix”?

Located in a sparsely populated area of the sky, this intriguing target is about a fist width due northwest of bright Formalhaut and about a fingerwidth west of Upsilon Aquarii. While the NGC 7293 (Right Ascension: 22 : 29.6 – Declination: -20 : 48) is also a planetary nebula, its entirely different than most… It’s a very large and more faded edition of the M57! On a clear, dark night it can be spotted with binoculars since it spans almost one quarter a degree of sky. Using a telescope, stay at lowest power and widest field, because it is so large. It you have an OIII filter, this faded “ring” becomes a braided treat!

Wednesday, September 12 – Today in 1959, the USSR’s Luna 2 scored a mark as it became the first manmade object to hit the moon. The successful mission landed in the Paulus Putredinus area. Today also celebrates the 1966 Gemini 11 launch.

Tonight let’s take the time to hunt down an often overlooked globular cluster – M56. Located roughly midway between Beta Cygni and Gamma Lyrae (RA 19 15 35.50 Dec +30 11 04.2), this class X globular was discovered by Charles Messier in 1779 on the same night he discovered a comet, and was later resolved by Herschel. At magnitude 8 and small in size, it’s a tough call for a beginner with binoculars, but is a very fine telescopic object. With a general distance of 33,000 light-years, this globular resolves well with larger scopes, but doesn’t show as much more than a faint, round area with small aperture. However, the beauty of the chains of stars in the field makes it quite worth the visit!

While you’re there, look carefully: M56 is one of the very few objects for which the photometry of its variable stars was studied strictly with amateur telescopes. While one bright variable star had been known previously to exist, up to a dozen more have recently been discovered. Of those, six had their variability periods determined using CCD photography and telescopes just like yours!

Thursday, September 13 – Today in 1922, the highest air temperature ever recorded at the surface of the Earth occurred. The measurement was taken in Libya and burned in at a blistering 136F (58C), but did you know that the temperatures in the sunlight on the Moon double that? If you thought the surface of the Moon was a bit too warm for comfort, then know surface temperatures on the closest planet to the Sun can reach up to 800F (427C) at the equator during the day! As odd as it may sound, even that close to the Sun – Mercury could very well have ice deposits hidden below the surface at its poles.

Tonight we’ll move on to Aquila and look at the hot central star of an interesting planetary nebula – NGC 6804 (Right Ascension: 19 : 31.6 – Declination: +09 : 13). You’ll find it almost 4 degrees due west of Altair. Discovered by Herschel and classed as open cluster H VI.38, it wasn’t until Pease took a closer look that its planetary nature was discovered. Interacting with clouds of interstellar dust and gases, NGC 6804 is a planetary in decline, with its outer shell around magnitude 12 and the central star at about magnitude 13. While only larger telescopes will get a glimpse of the central, it’s one of the hottest objects in space – with temperatures around 30,000K!

If that’s not “hot” enough for you, then take a look straight overhead at brilliant star Vega. It is a “Sirian type” star and with a surface temperature of about 9200 degrees Kelvin, it’s twice as hot as our own Sun. At around 27 light years away, our entire solar system is moving towards Vega at a speed of 12 miles per second, but don’t worry… It will take us another 450,000 years to get there. If we were to arrive tonight, we’d find that Vega is around 3 times larger than Sol and that it also has a 10th magnitude companion that can often be resolved in mid-sized scopes. It’s one of the first stars to ever be photographed. Back in 1850, that simple star – Vega – took and exposure time of 100 seconds through a 15? scope. How times have changed!

Friday, September 14 – Tonight’s destination is not an easy one, but if you have a 6? or larger scope, you’ll fall in love a first sight! Let’s head for Eta Pegasi and slightly more than 4 degrees north/northeast for NGC 7331 (Right Ascension: 22 : 37.1 – Declination: +34 : 25).

This beautiful, 10th magnitude, tilted spiral galaxy is very much how our own Milky Way would appear if we could travel 50 million light years away and look back. Very similar in both structure to ourselves and the “Great Andromeda”, this particular galaxy gains more and more interest as scope size increases – yet it can be spotted with larger binoculars. At around 8? in aperture, a bright core appears and the beginnings of wispy arms. In the 10? to 12? range, spiral patterns begin to emerge and with good seeing conditions, you can see “patchiness” in structure as nebulous areas are revealed and the western half is deeply outlined with a dark dustlane. But hang on… Because the best is yet to come!

Saturday, September 15 – In 1991 the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS) was launched from Space Shuttle Discovery. The successful mission lasted well beyond its life expectancy – sending back critical information about our ever-changing environment. After 14 years and 78,000 orbits, UARS remains a scientific triumph.

If you’re up early, why not check out Mars? While the red planet is visible, it’s also rather small at the moment, with an apparent diameter of less than .5”. Can you still spot some surface details?

Tonight return to the NGC 7331 with all the aperture you have. What we are about to look at is truly a challenge and requires dark skies, optimal position and excellent conditions. Now breathe the scope about one half a degree south/southwest and behold one of the most famous galaxy clusters in the night.

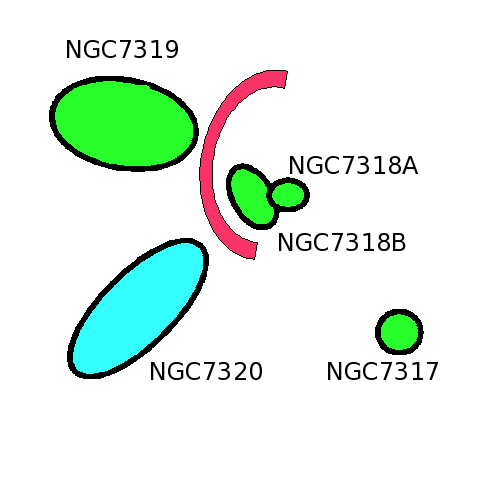

In 1877, French astronomer – Edouard Stephan was using the first telescope designed with a reflection coated mirror when he discovered something a bit more with the NGC 7331. He found a group of nearby galaxies! This faint gathering of five is better known as “Stephan’s Quintet” and its members are no further apart than our own Milky Way galaxy.

Visually in a large scope, these members are all rather faint, but their proximity is what makes them such a curiosity. The Quintet is made up of five galaxies numbered NGC 7317, 7318, 7318A, 7318B, 7319 and the largest is 7320 (Right Ascension: 22 : 36.1 – Declination: +33 : 57). Even with a 12.5? telescope, this author has never seen them as much more than tiny, barely there objects that look like ghosts of rice grains on a dinner plate. So why bother?

What our backyard equipment can never reveal is what else exists within this area – more than 100 star clusters and several dwarf galaxies. Some 100 million years ago, the galaxies collided and left long streamers of their materials which created star forming regions of their own, and this tidal pull keeps them connected. The stars within the galaxies themselves are nearly a billion years old, but between them lay much younger ones. Although we cannot see them, you can make out the soft sheen of the galactic nucleii of our interacting group.

Enjoy their faint mystery!

Sunday, September 16 – It’s New Moon! For those of you who have waited on the weekend to enjoy dark skies, then let’s add another awesome galaxy to the collection. Tonight set your sights towards Alpha Pegasi and drop due south less than 5 degrees to pick up NGC 7479 (Right Ascension: 23 : 04.9 – Declination: +12 : 19).

Discovered by William Herschel in 1784. this tantalizing 11 magnitude barred spiral galaxy has had a supernova in its nucleus as recently as 1990. While the 16th magnitude event is no longer visible, smaller telescopes will easily pick out bright core and elongation of the central bar. Larger aperture will find this one a real treat as the spiral arms curl both over and under the central structure, resembling a ballet dancer “en pointe”. Congratulations! You’ve just observed Caldwell 44.

Until next week? Wishing you clear skies!

Written by Tammy Plotner. NGC 7009 Image Credit: NOAO/AURA/NSF