At one time or another, all science enthusiasts have heard the late Carl Sagan’s infamous words: “We are made of star stuff.” But what does that mean exactly? How could colossal balls of plasma, greedily burning away their nuclear fuel in faraway time and space, play any part in spawning the vast complexity of our Earthly world? How is it that “the nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies” could have been forged so offhandedly deep in the hearts of these massive stellar giants?

Unsurprisingly, the story is both elegant and profoundly awe-inspiring.

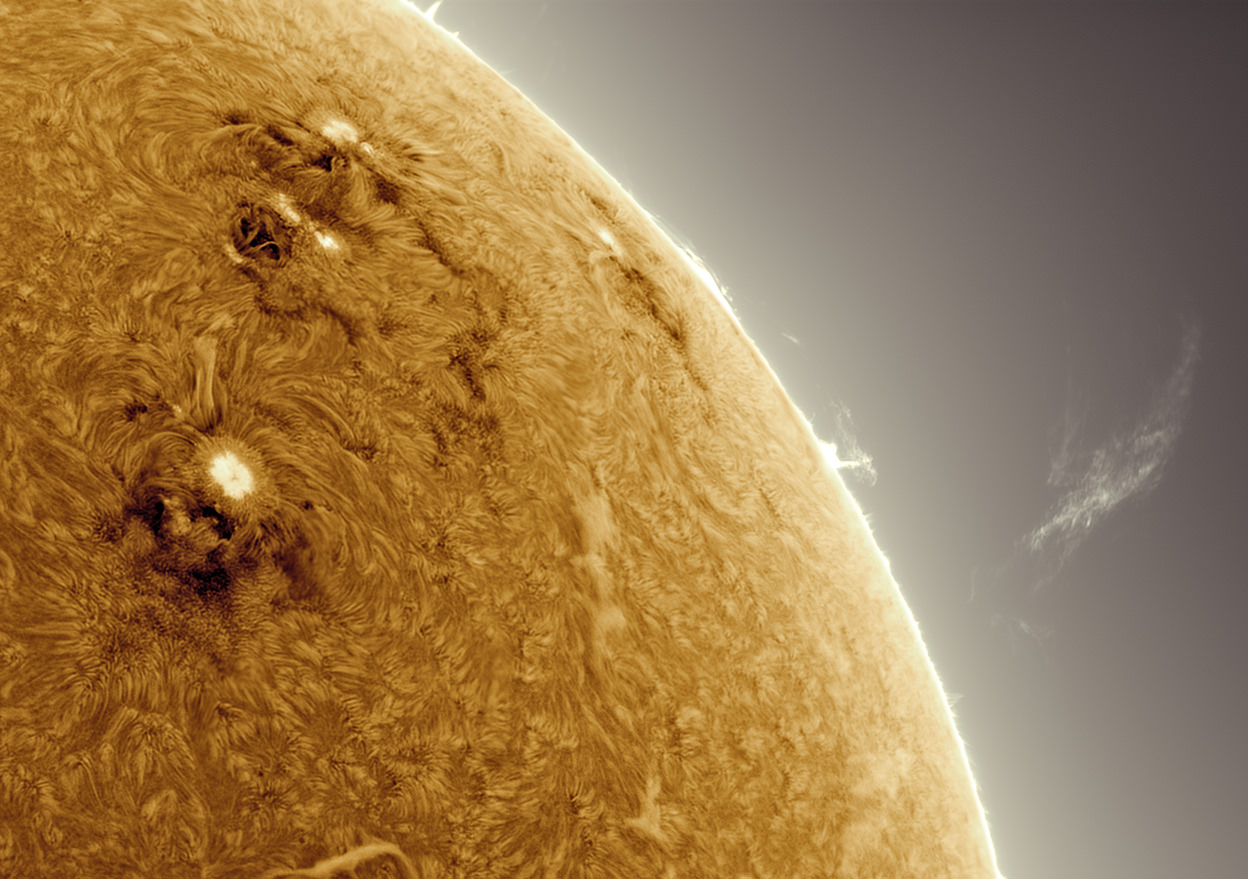

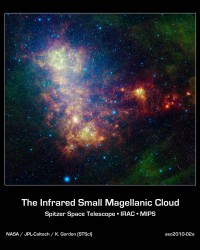

All stars come from humble beginnings: namely, a gigantic, rotating clump of gas and dust. Gravity drives the cloud to condense as it spins, swirling into an ever more tightly packed sphere of material. Eventually, the star-to-be becomes so dense and hot that molecules of hydrogen in its core collide and fuse into new molecules of helium. These nuclear reactions release powerful bursts of energy in the form of light. The gas shines brightly; a star is born.

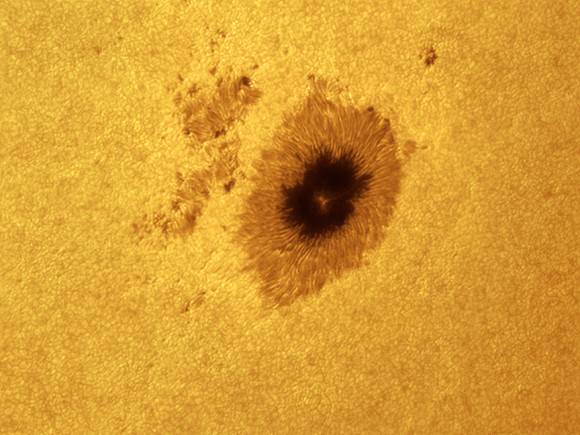

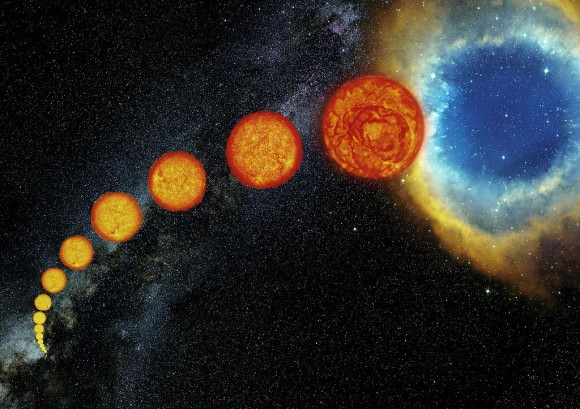

The ultimate fate of our fledgling star depends on its mass. Smaller, lightweight stars burn though the hydrogen in their core more slowly than heavier stars, shining somewhat more dimly but living far longer lives. Over time, however, falling hydrogen levels at the center of the star cause fewer hydrogen fusion reactions; fewer hydrogen fusion reactions mean less energy, and therefore less outward pressure.

At a certain point, the star can no longer maintain the tension its core had been sustaining against the mass of its outer layers. Gravity tips the scale, and the outer layers begin to tumble inward on the core. But their collapse heats things up, increasing the core pressure and reversing the process once again. A new hydrogen burning shell is created just outside the core, reestablishing a buffer against the gravity of the star’s surface layers.

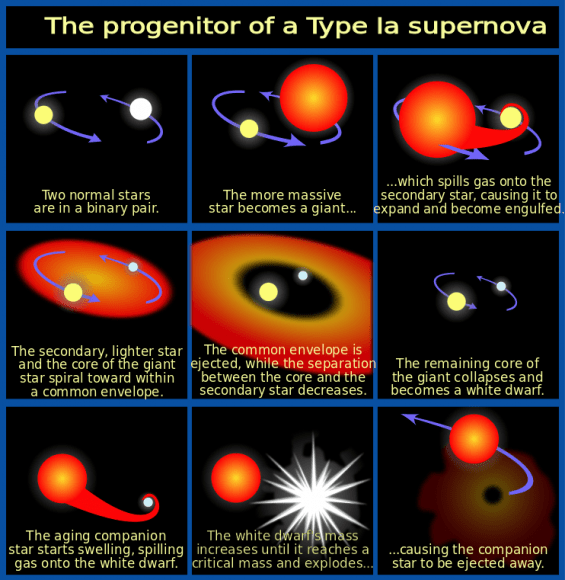

While the core continues conducting lower-energy helium fusion reactions, the force of the new hydrogen burning shell pushes on the star’s exterior, causing the outer layers to swell more and more. The star expands and cools into a red giant. Its outer layers will ultimately escape the pull of gravity altogether, floating off into space and leaving behind a small, dead core – a white dwarf.

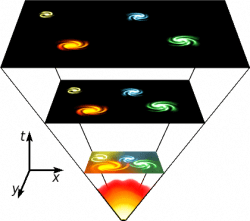

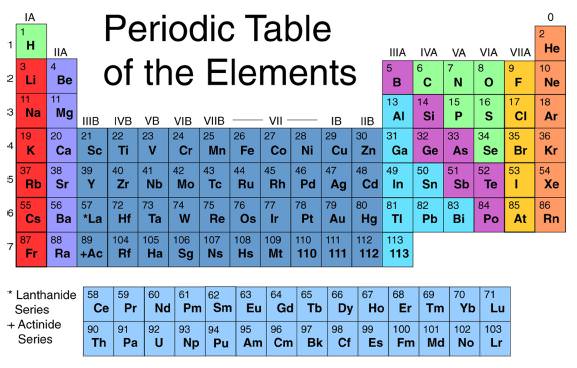

Heavier stars also occasionally falter in the fight between pressure and gravity, creating new shells of atoms to fuse in the process; however, unlike smaller stars, their excess mass allows them to keep forming these layers. The result is a series of concentric spheres, each shell containing heavier elements than the one surrounding it. Hydrogen in the core gives rise to helium. Helium atoms fuse together to form carbon. Carbon combines with helium to create oxygen, which fuses into neon, then magnesium, then silicon… all the way across the periodic table to iron, where the chain ends. Such massive stars act like a furnace, driving these reactions by way of sheer available energy.

But this energy is a finite resource. Once the star’s core becomes a solid ball of iron, it can no longer fuse elements to create energy. As was the case for smaller stars, fewer energetic reactions in the core of heavyweight stars mean less outward pressure against the force of gravity. The outer layers of the star will then begin to collapse, hastening the pace of heavy element fusion and further reducing the amount of energy available to hold up those outer layers. Density increases exponentially in the shrinking core, jamming together protons and electrons so tightly that it becomes an entirely new entity: a neutron star.

At this point, the core cannot get any denser. The star’s massive outer shells – still tumbling inward and still chock-full of volatile elements – no longer have anywhere to go. They slam into the core like a speeding oil rig crashing into a brick wall, and erupt into a monstrous explosion: a supernova. The extraordinary energies generated during this blast finally allow the fusion of elements even heavier than iron, from cobalt all the way to uranium.

The energetic shock wave produced by the supernova moves out into the cosmos, disbursing heavy elements in its wake. These atoms can later be incorporated into planetary systems like our own. Given the right conditions – for instance, an appropriately stable star and a position within its Habitable Zone – these elements provide the building blocks for complex life.

Today, our everyday lives are made possible by these very atoms, forged long ago in the life and death throes of massive stars. Our ability to do anything at all – wake up from a deep sleep, enjoy a delicious meal, drive a car, write a sentence, add and subtract, solve a problem, call a friend, laugh, cry, sing, dance, run, jump, and play – is governed mostly by the behavior of tiny chains of hydrogen combined with heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphorus.

Other heavy elements are present in smaller quantities in the body, but are nonetheless just as vital to proper functioning. For instance, calcium, fluorine, magnesium, and silicon work alongside phosphorus to strengthen and grow our bones and teeth; ionized sodium, potassium, and chlorine play a vital role in maintaining the body’s fluid balance and electrical activity; and iron comprises the key portion of hemoglobin, the protein that equips our red blood cells with the ability to deliver the oxygen we inhale to the rest of our body.

So, the next time you are having a bad day, try this: close your eyes, take a deep breath, and contemplate the chain of events that connects your body and mind to a place billions of lightyears away, deep in the distant reaches of space and time. Recall that massive stars, many times larger than our sun, spent millions of years turning energy into matter, creating the atoms that make up every part of you, the Earth, and everyone you have ever known and loved.

We human beings are so small; and yet, the delicate dance of molecules made from this star stuff gives rise to a biology that enables us to ponder our wider Universe and how we came to exist at all. Carl Sagan himself explained it best: “Some part of our being knows this is where we came from. We long to return; and we can, because the cosmos is also within us. We’re made of star stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself.”