“There is no problem so bad that you can’t make it worse.” So with that old astronaut principle in mind, what is the best reaction to take when your eyes become blinded while you’re working on the International Space Station, in no more protection than with a spacesuit?

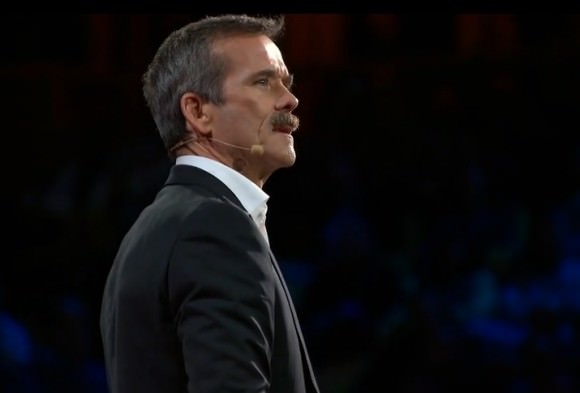

The always eloquent Canadian (retired) astronaut Chris Hadfield — commander of Expedition 35 — faced this situation in 2001. He explains the best antidotes to fear: knowledge, practice and understanding. And in this TED talk uploaded this week, he illustrates how to conquer some dangers in space with the simple analogy of walking into a spiderweb.

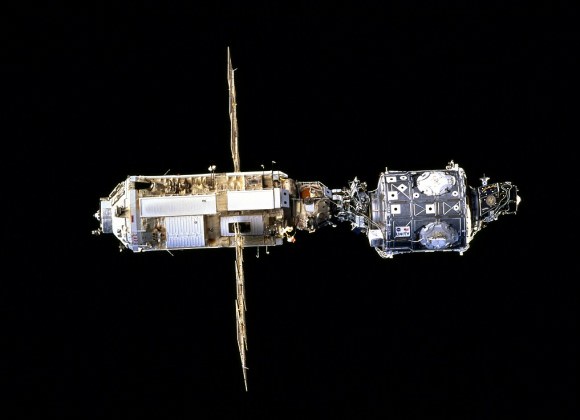

Say you’re terrified of spiders, worried that one is going to poison you and kill you. The first best thing to do is look at the statistics, Hadfield said. In British Columbia (where the talk was held), there is only one poisonous spider among hundreds. In space, the odds are grimmer: a 1 in 9 chance of catastrophic failure in the first five shuttle flights, and something like 1 in 38 when Hadfield took his first shuttle flight in 1995 to visit the space shuttle Mir.

So how do you deal with the odds? For spiders, control the fear, walk through spiderwebs as long as you see there’s nothing poisonous lurking. For space? “We don’t practice things going right, but we practice things going wrong, all the time so you are always walking through those spiderwebs,” Hadfield said.

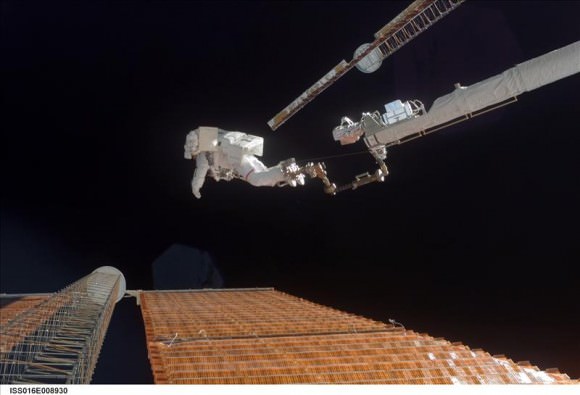

And then he tells the tale of his 2001 spacewalk during STS-100 when he was outside, blinded by a substance in his helmet, trying to work through the problem. (The incident has even more resonance today, just a few months after an Italian astronaut had a life-threatening water leak in his NASA spacesuit.)

Be sure to watch the talk to the end, as Hadfield has a treat for the audience. And as always, listening to Hadfield’s descriptions of space is a joy: “A self propelled art gallery of fantastic changing beauty that is the world itself,” is among the more memorable phrases of the talk.

TED, a non-profit that bills itself as one that spreads ideas, charged a hefty delegate fee for attendees at this meeting (reported at $7,500 each) but did free livestreaming at several venues in the Vancouver area. It also makes its talks available on the web for free.

Hadfield rocketed to worldwide fame last year after doing extensive social media and several concerts from orbit.