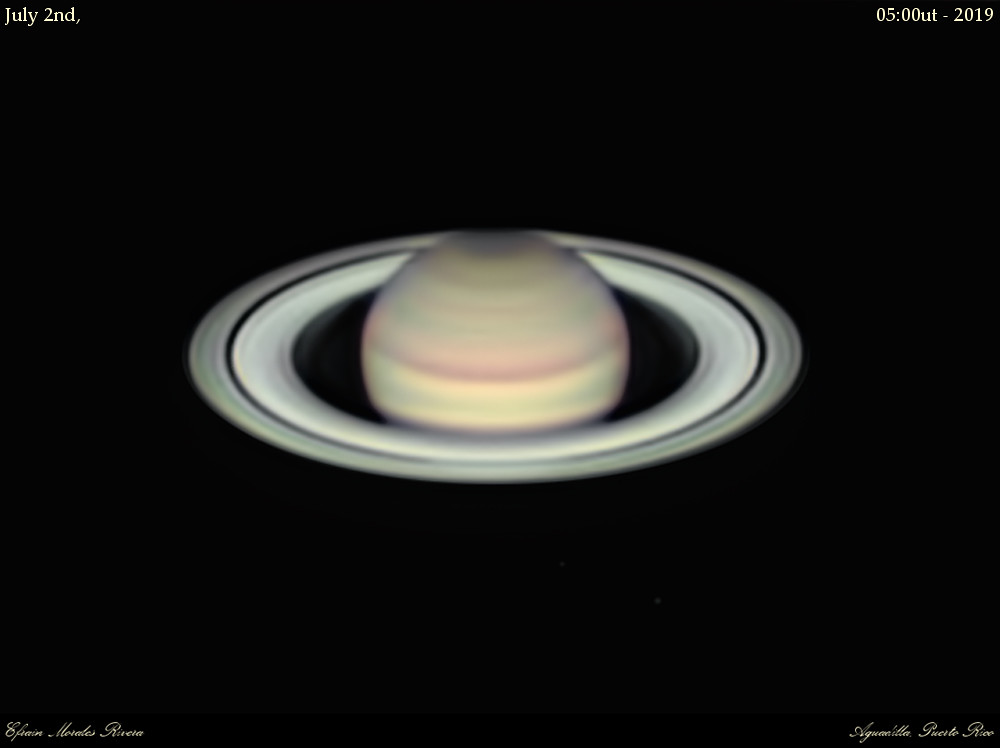

Saturn opposition season never disappoints. Slowly, one by one, the planets are returning to the dusk sky. In June, we had Jupiter reach opposition on June 10th. Now, although Mercury and Mars are fleeing the evening scene low to the west at dusk and Venus lingers low in the dawn, magnificent Saturn reaches opposition tonight on July 9th, rising to the east as the Sun sets to the west.

Continue reading “Our Guide to Saturn Opposition Season 2019”Planets on Parade: Saturn at Opposition 2018

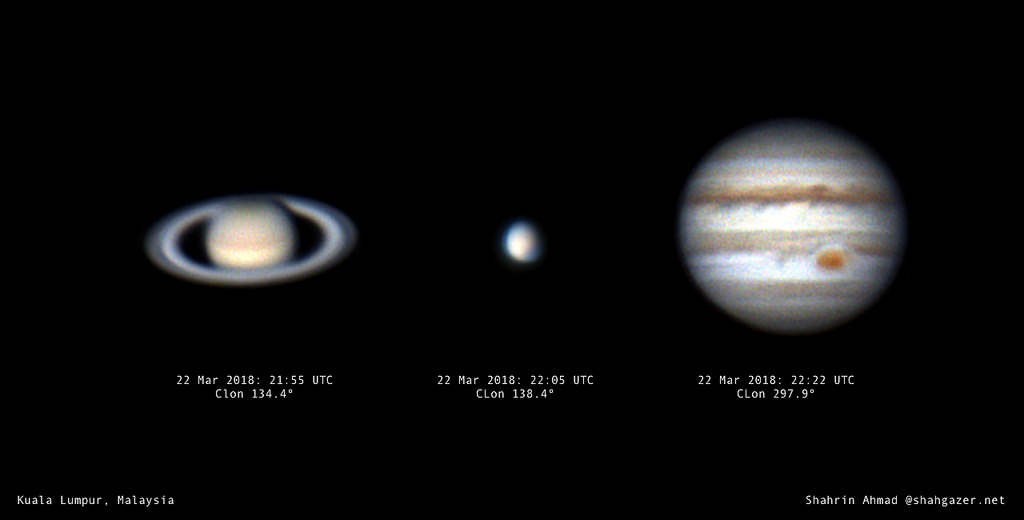

We’re in the midst of a parade of planets crossing the evening sky. Jupiter reached opposition on May 9th, and sits high to the east at dusk. Mars heads towards a fine opposition on July 27th, nearly as favorable as the historic opposition of 2003. And Venus rules the dusk sky in the west after the setting Sun for most of 2018.

June is Saturn’s turn, as the planet reaches opposition this year on June 27th, rising opposite to the setting Sun at dusk.

In classical times, right up until just over two short centuries ago, Saturn represented the very outer limit of the solar system, the border lands where the realm of the planets came to an end. Sir William Herschel extended this view, when he spied Uranus—the first planet discovered in the telescopic era—slowly moving through the constellation Gemini just across the border of Taurus the Bull using a 7-foot reflector (in the olden days, telescopes specs were often quoted referring to their focal length versus aperture) while observing from his backyard garden in Bath, England on the night of March 13th, 1781.

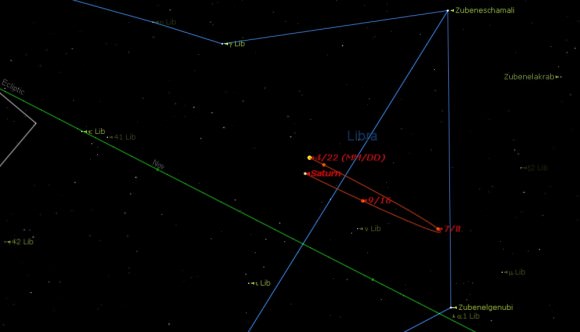

Orbiting the Sun once every 29.5 years, Saturn is the slowest moving of the naked eye planets, fitting for a planet named after Father Time. Saturn slowly loops from one astronomical constellation along the zodiac to the next eastward, moving through one about every two years.

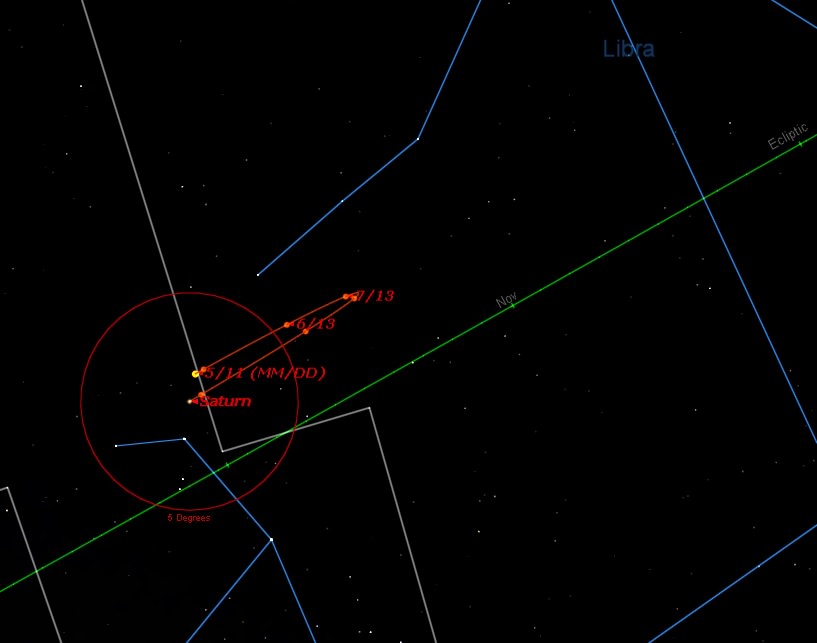

2018 sees Saturn in the constellation Sagittarius the Archer, just above the ‘lid’ of the Teapot asterism, favoring the southern hemisphere for this apparition. Saturn won’t cross the celestial equator northward again until 2026. Not that that should discourage northern hemisphere viewers from going after this most glorious of planets. A low southerly declination also means that Saturn is also up in the evening in the summertime up north, a conducive time for observing. Taking 29-30 years to complete one lap around the ecliptic as seen from our Earthly vantage point, Saturn also makes a great timekeeper with respect to personal life milestones… where were you back in 1989, when Saturn occupied the same spot along the ecliptic?

Saturn also shows the least variation of all the planets in terms of brightness and size, owing to its immense distance 9.5 AU from the Sun, and consequently 8.5 to 10.5 AU from the Earth. Saturn actually just passed its most distant aphelion since 1959 on April 17th, 2018 at 10.066 AU from the Sun.

Saturn’s in 2018 Dates with Destiny

Saturn sits just 1.6 degrees south of the waning gibbous Moon tonight. The Moon will lap it again one lunation later on June 28th. Note that the brightest of the asteroids, +5.7 magnitude 4 Vesta is nearby in northern Sagittarius, also reaching opposition on June 19th. Can you spy Vesta with the naked eye from a dark sky site? 4 Vesta passes just 4 degrees from Saturn on September 23rd, and both flirt with the galactic plane and some famous deep sky targets, including the Trifid and Lagoon Nebulae.

Saturn reaches quadrature 90 degrees east of the Sun on September 25th, then ends its evening apparition when it reaches solar conjunction on New Year’s Day, 2019.

Saturn is well clear of the Moon’s path for most of this year, but stick around: starting on December 9th, 2018, the slow-moving planet will make a great target for the Moon, which will begin occulting it for every lunation through the end of 2019.

It’s ironic: Saturn mostly hides its beauty to unaided eye. Presenting a slight saffron color in appearance, it never strays much from magnitude -0.2 to +1.4 in brightness. One naked eye observation to watch for is a sudden spurt in brightness known as the opposition surge or Seeliger Effect. This is a retro reflector type effect, caused by all those tiny iceball moonlets in the rings reaching 100% illumination at once. Think of how the Full Moon is actually 3 to 4 times brighter than the 50% illuminated Quarter Moon… all those little peaks, ridges and crater rims no longer casting shadows do indeed add up.

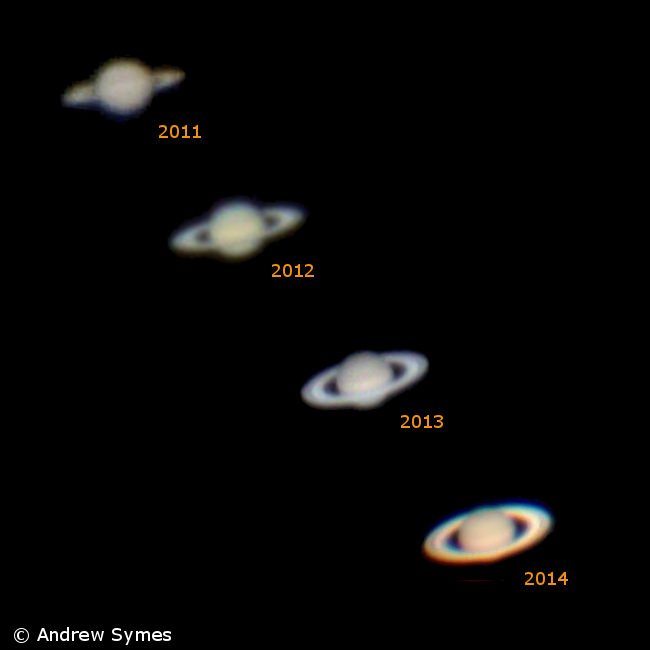

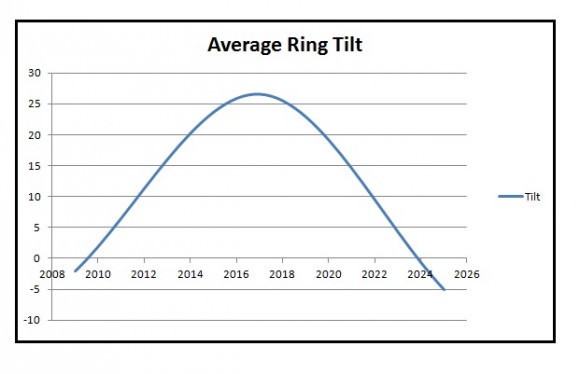

And this effect is more prominent in recent years for another reason: Saturn’s rings passed maximum tilt (26.7 degrees) with respect to our line of sight just last year, and are still relatively wide open in 2018. They’ll start slimming down again over the next few oppositions, reaching edge-on again in 2028.

Even using a pair of 7×50 hunting binoculars on Saturn, you can tell that something is amiss. You’re getting the same view that Galileo had through his spyglass, the pinnacle of early 17th century technology. He could tell that something about the planet was awry, and drew sketches showing an oblong world with coffee cup handles on the side. Crank up the magnification using even a small 60 mm refractor, and the rings easily jump into view. This is what makes Saturn a star party staple, an eye candy feast capable of drawing the aim of all the telescopes down the row.

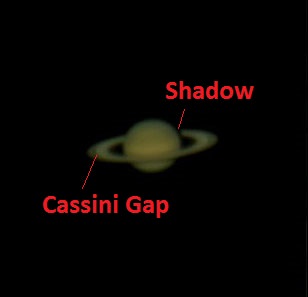

If seeing and atmospheric conditions allow, crank up the magnification up to 150x or higher, and the dark groove of the Cassini division snaps into view. Can you see the shadow of the disk of Saturn, cast back onto the plane of the rings? The shadow of the planet hides behind it near opposition, then becomes most prominent towards quadrature, when we get to peek around its edge. Can you spy the limb of the planet itself, through the Cassini Gap?

Though the disk of Saturn is often featureless, tiny swirls of white storms do occasionally pop up. Astrophotographer Damian Peach noted just one such short-lived storm on the ringed planet this past April 2018.

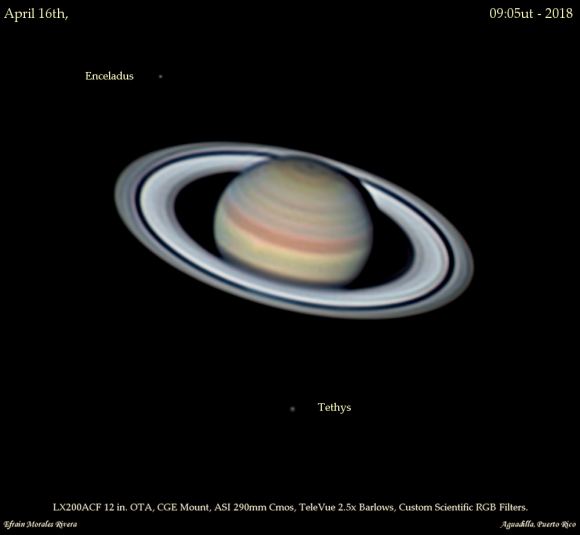

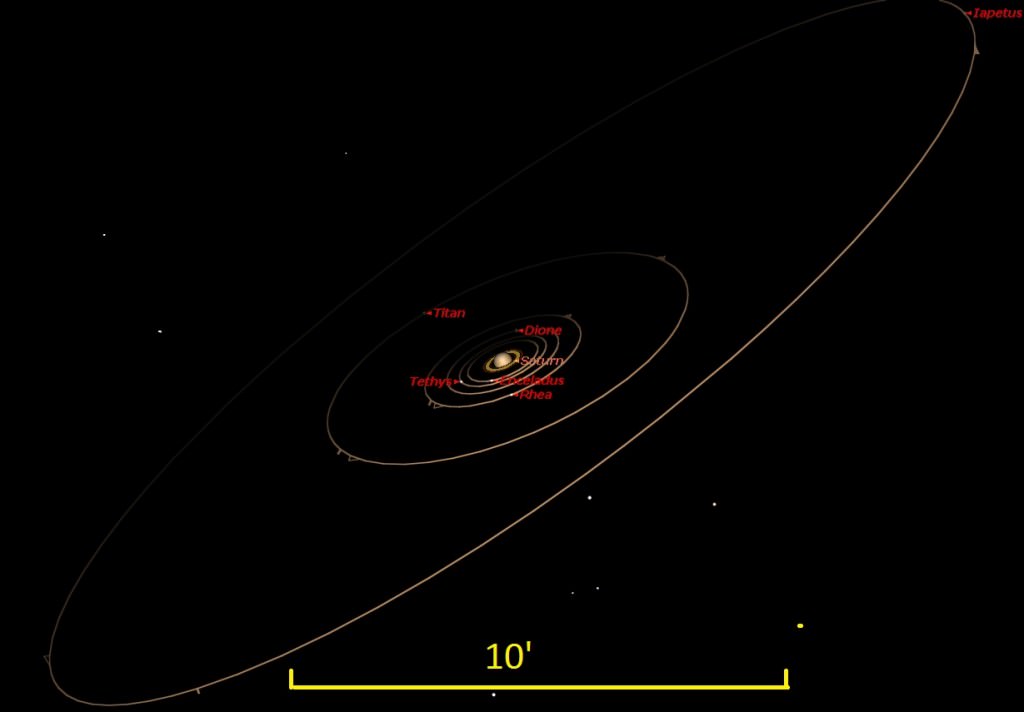

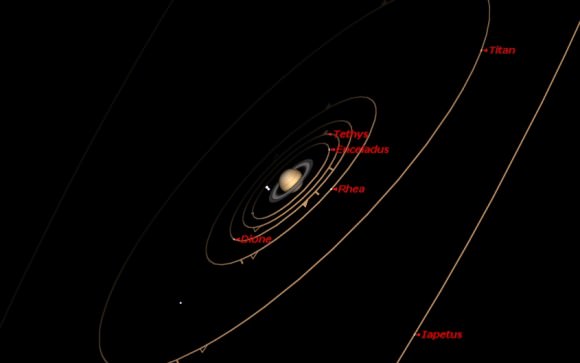

Saturn’s retinue of moons are also interesting to follow in there own right. The first one you’ll note is +8.5 magnitude smog-shrouded Titan. Larger in diameter than Mercury, Titan would easily be a planet in its own right, were it liberated from its primary’s domain.

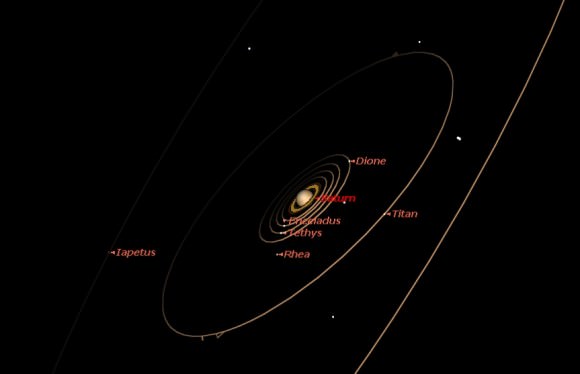

Though Saturn has 62 known moons, only six in addition to Titan are in range of a modest backyard telescope: Enceladus, Rhea, Dione, Mimas, Tethys and Iapetus. Two-faced Iapetus is especially interesting to follow, as it varies two full magnitudes in brightness during its 79 day orbit. Arthur C. Clarke originally placed the final monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey on this moon, its artificial coating a beacon to astronomers. Today, we know from flybys carried out by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft that the leading hemisphere of Iapetus is coated with dark in-falling material, originating from the dark Phoebe ring around Saturn.

Owners of large light bucket telescopes may also want to try from two fainter +15th magnitude moons: Hyperion and Phoebe.

Fun fact: Saturn’s moons can also cast shadows back on the planet itself, much like the Galilean moons do on Jupiter… the catch, however, is that these events only occur around equinox season in the years around when Saturn’s rings are edge-on. This next occurs starting in 2026.

Cassini finished up its thrilling 20 year mission just last year, with a dramatic plunge into Saturn itself. It will be a while before we return again, perhaps in the next decade if NASA selects a nuclear-powered helicopter to explore Titan. Until then, be sure to explore Saturn this summer, from your Earthbound backyard.

Love to observe the planets? Check out our new forthcoming book, The Universe Today Ultimate Guide to Viewing the Cosmos – out on October 23rd, now up for pre-order.

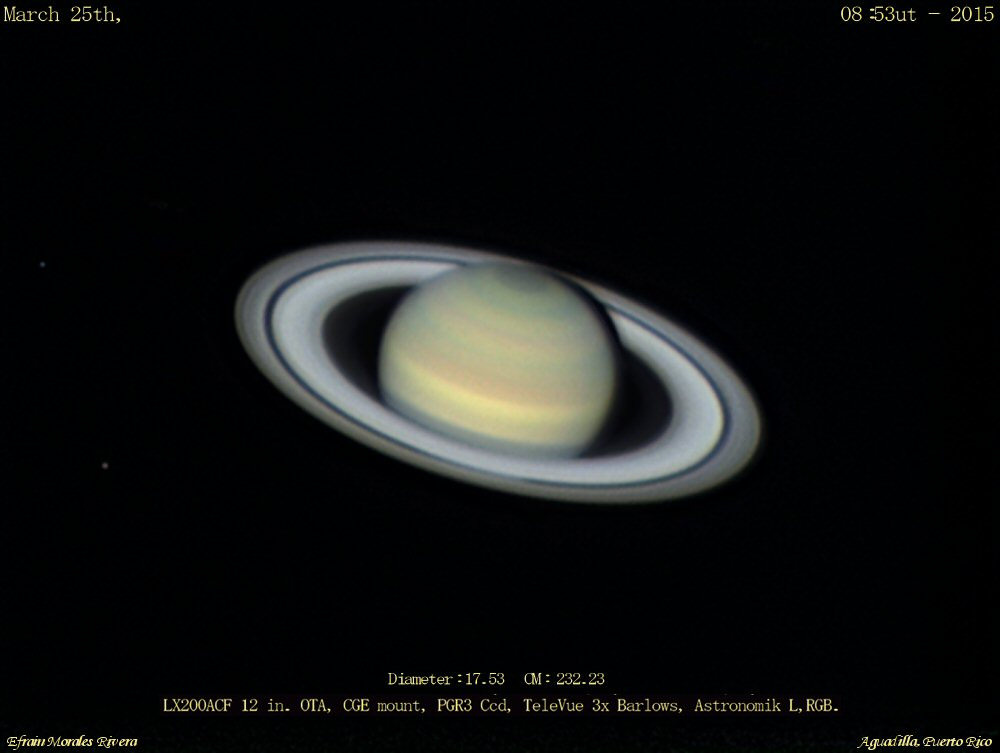

A Guide to Saturn Through Opposition 2015

The month of May generally means the end of star party season here in Florida, as schools let out in early June, and humid days make for thunderstorm-laden nights. This also meant that we weren’t about to miss the past rare clear weekend at Starkey Park. Jupiter and Venus rode high in the sky, and even fleeting Mercury and a fine pass of the Hubble Space Telescope over central Florida put in an appearance.

But the ‘star’ of the show was the planet Saturn as it appeared at nightfall low to the southeast. Currently rising about 9:00 PM local, Saturn is joining the evening skies as it approaches opposition next week.

This also means we’ve got every naked eye planet set for prime time evening viewing this week with the exception of Mars, which reaches solar conjunction on June 14, 2015. Mercury will be the first world to break this streak, as it descends into the twilight glare by mid-May.

Saturn reaches opposition for 2015 on May 23rd at 1:00 Universal Time (UT), which equates to 9:00 PM EDT the evening prior on May 22 at nearly 9 astronomical units (AU) distant. Oppositions of Saturn are getting slightly more distant to the tune of 10 million kilometers in 2015 versus last year as Saturn heads towards aphelion in 2018. Saturn crosses eastward from the astronomical constellation of Scorpius in the first week of May, and spends most of the remainder of 2015 in Libra before looping back into the Scorpion in mid-October. The first of June finds Saturn just over a degree southward of the +4th magnitude star Theta Librae. Saturn takes nearly 30 Earth years to complete one orbit, meaning that it was right around the same position in the sky in 1985, and will appear so again in 2045. Relatively speedy Jupiter also overtakes Saturn as seen from the Earth about once every 20 years, as it last did on 2000 and is set to do so again in 2020.

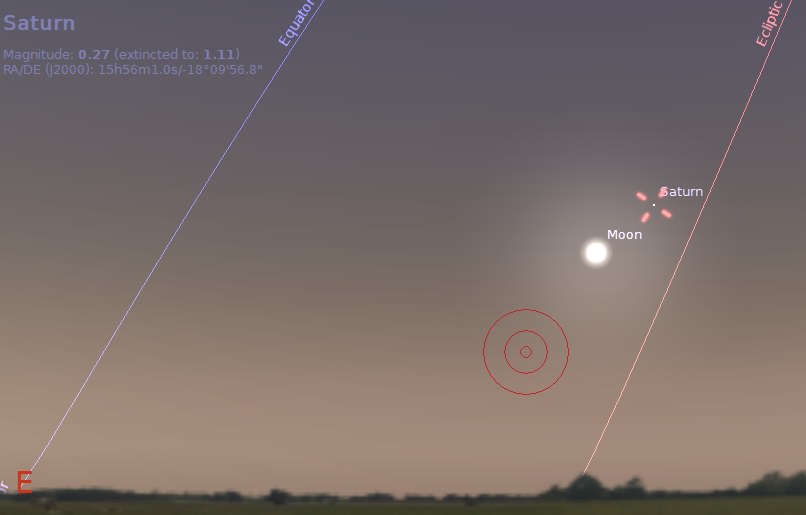

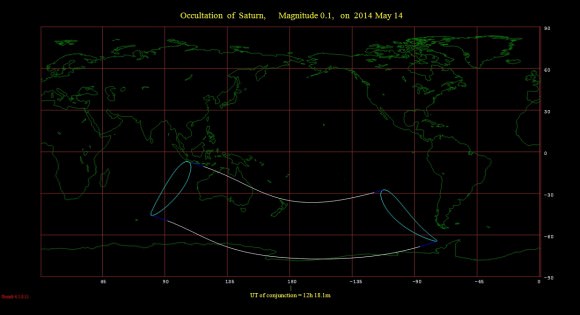

And though series of occultations of Saturn by the Moon wrapped up in 2014 and won’t resume again until December 9, 2018, there’s also a good chance to spy Saturn two degrees away from the daytime Moon with binoculars on June 1st just 24 hours prior to Full:

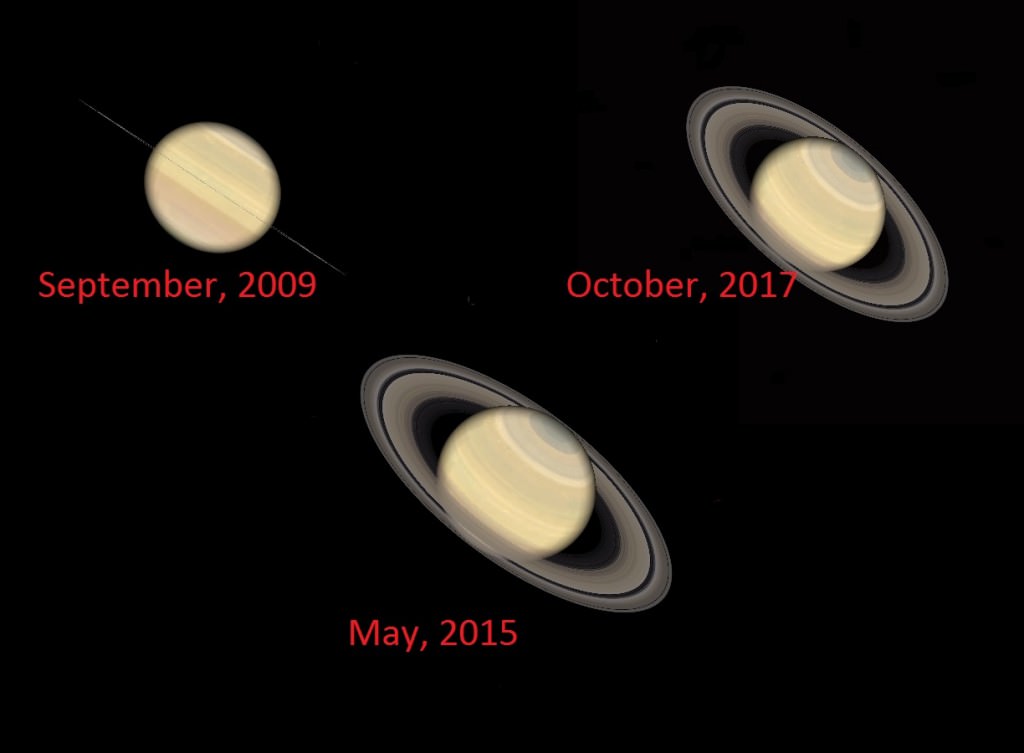

The tilt of the rings of Saturn is also slowly widening from our Earthbound perspective. At opposition, Saturn’s rings subtend 43” across, and the ochre disk of Saturn itself spans 19”. Incidentally, on a good pass, the International Station has a visual span roughly equivalent to Saturn plus rings. In 2015, the rings are tilted 24 degrees wide and headed for a maximum approaching 27 degrees in 2017. The rings appeared edge on in 2009 and will do so again in 2025.

Also, keep an eye out for the Seeliger effect. Also sometimes referred to as the ‘opposition surge,’ this is a retroreflector-style effect that causes an outer planet to brighten up substantially on the days approaching opposition. In the case of Saturn and its rings, this effect can be especially dramatic. Not only is the disk of Saturn and the billions of icy snowballs casting shadows nearly straight back as seen from our vantage point near opposition, but a phenomenon known as coherent backscatter serves to increase the collective brightness of Saturn as well. You see the same effect at work as you drive down the Interstate at night, and highway signs and retroreflector markers down the center of the road bounce your high-beams back at you.

We’ve seen some pretty nifty image comparisons demonstrating the Seeliger effect on Saturn, but as of yet, we haven’t seen an animation of the same. Certainly, such a feat is well within the capacities of amateur astronomers out there… hey, we’re just throwing that possibility out into the universe.

Through a small telescope, the moons of Saturn become readily apparent. The brightest of them all is Titan at magnitude +9, orbiting Saturn once every 16 days. Discovered by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens on March 25, 1655 using a 63 millimeter refractor with an amazing 337 centimeter focal length, Titan would easily be a planet in its own right were it directly orbiting the Sun. Titan also marks the most distant landing of a spacecraft ever carried out by our species, with the descent of the European Space Agency’s Huygens lander on January 14, 2005. Huygens hitched a ride to Saturn aboard NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which is slated to end its mission with a destructive reentry over the skies of Saturn in 2017. Saturn has 62 known moons in all, and Enceladus, Mimas, Tethys, Dione, Rhea and two-faced Iapetus are all visible from a backyard telescope.

You can check out the current position of Saturn’s major moons (excluding Iapetus) here.

And speaking of Iapetus, the outer moon would make a fine Saturn-viewing vantage point, as it is the only major moon with an inclined orbit out of the ring plane of Saturn:

Expect our Saturn observing resort to open there one day soon.

Up for a challenge? Standard features to watch for include: the shadow of the rings on the planet, and the shadow of the planet across the rings, as well as the Cassini division between the A and B ring… but can you see the disk of the planet through the gap? High magnification and steady seeing are your friends in this feat of visual athletics… catching sight of it definitely adds a three dimensional quality to the overall view.

Let ‘the season of Saturn 2015’ begin!

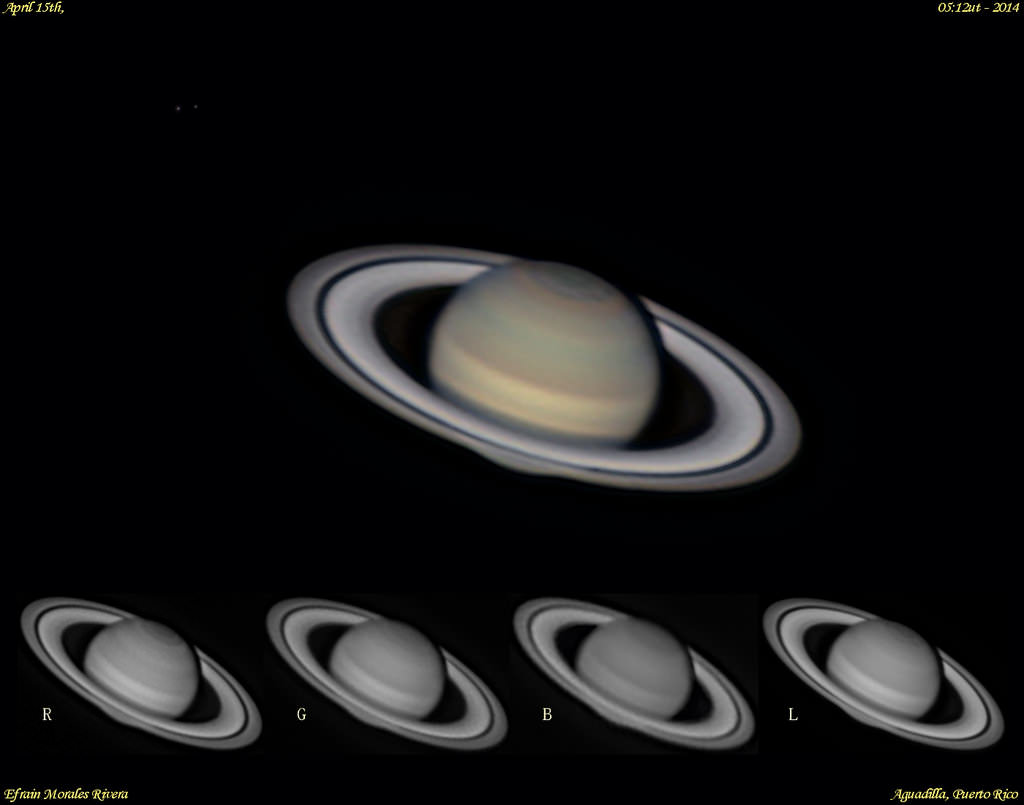

Saturn at Opposition: Our 2014 Guide

Planet lovers can rejoice: one of the finest jewels of the solar system in returning to the evening night sky.

The planet Saturn reaches opposition next month on May 10th. This means that as the Sun sets to the west, Saturn will rise “opposite” to it in the east, remaining well positioned for observation in the early evening hours throughout the summer season. In fact, we’ll have four of the five naked eye planets above the horizon at once for our evening viewing pleasure in the month of May, as Jupiter also rides high to the west at sunset, Mars just passed opposition last month and Mercury reaches greatest eastern elongation on May 25th. Venus is the solitary holdout, spending a majority of 2014 in the dawn sky.

Saturn will shine at magnitude +0.3 this month and its disk spans an apparent 19,” or 44” if you take into account the apparent width of its rings. The rings are currently tipped open 22 degrees with respect to our line of sight. The ring opening is widening, and will reach a maximum of over 25 degrees in 2017 before the trend reverses. Anyone who remembers observing Saturn back in 2009 will recall that its rings were edge on to our view. This widening of Saturn’s rings also lends itself to a curious effect: although we’re in a cycle of oppositions that are getting farther away — Saturn is 12.5 million kilometres or 0.083 Astronomical Units (A.U.s) more distant in 2014 than it was during opposition last year as it’s headed towards aphelion in 2018 — its widening rings are actually making it appear a bit brighter.

This year’s opposition will find Saturn in the astronomical constellation of Libra, where it’ll spend most of 2014. Oppositions of the ringed planet are set to continue to “head south” until 2018, and won’t occur north of the celestial equator again until 2026. I remember when oppositions of Saturn returned to the constellation Virgo a few years back — where I had first looked at it with my 60mm Jason refractor as a teenager — and realizing that I had now been into observational astronomy for roughly one “Saturnian year.”

The ancients had little knowledge of how unique Saturn was. The faintest and slowest moving of the classical planets, even Galileo knew that something was up when he turned his first primitive telescope towards it. His sketches depict Saturn as something similar to a double handled coffee cup, a testament to how poor his view really was. It wouldn’t be until Christiaan Huygens in 1655 that the true nature of Saturn’s rings was deduced as a flat and separate feature from the disk.

At opposition, the disk of the planet casts a shadow straight back from our point of view. This vantage slowly changes as the planet moves towards eastern quadrature on August 9th and we get a glimpse slightly off to one side of the planet. After opposition, the shadow of the disk can again be seen casting back onto the rings.

Another interesting phenomenon to watch out for near opposition is known as the Seeliger effect. Also sometimes referred to as the “opposition surge,” this sudden brightening of the disk and rings is a subtle effect, as the globe of Saturn and all of those tiny little ice crystals reach 100% illumination. This effect can be noted to the naked eye on successive nights around opposition, and will get more prominent towards 2017. Coherent-backscattering of light has also been proposed as a possible explanation of this phenomenon. Perhaps a video sequence capturing this effect is in order for skilled astro-imagers in 2014.

Through a small telescope, the first feature that becomes apparent is Saturn’s glorious system of rings. Crank up the magnification, and you’ll note a dark groove in the ring system. This is the Cassini Division, first described by Giovanni Cassini in 1675.

Here’s a challenge we came across some years back: can you see the disk of Saturn through the Cassini Division? Right around opposition is a good time to attempt this unusual feat of visual athletics.

Saturn’s large moon Titan is an easy catch at magnitude +8 in a small telescope. Titan is the second largest moon in the solar system. Place it in a direct orbit about the Sun, and it would be considered a planet, no problem. 7 of Saturn’s 62 known moons are within reach of a small telescope. In addition to Titan, they are, with quoted magnitudes: Mimas (+13), Enceladus (+12), Tethys (+10), Rhea (+10), Dione (+11) and Iapetus. Iapetus is of special interest, as it brightens from +11.9 to magnitude +10.2 as it traces out its 79 day orbit. We always knew there was something unique about this moon, and NASA’s Cassini mission revealed the world to have two distinctly different hemispheres with vastly different albedos during its close 2007 flyby.

Also, be sure to check out Saturn on the night of May 14th — just 4 nights after opposition — as the Full Moon sits less than a degree south of the ringed planet. Can you see both in the same telescopic field of view? Can you nab Saturn next to the rising daytime Moon low to the horizon just before local sunset? The Moon will actually occult (pass in front of) Saturn for viewers based in Australia and New Zealand on the 14th. This is only one of 11 occultations — nearly one for each lunation — of Saturn by the Moon in 2014. Unfortunately, the best one for North America occurs in the daytime on August 31st, though it too may be observable telescopically.

Finally, this evening apparition of the planet runs through northern hemisphere summer and fall until Saturn reaches solar conjunction on November 18th. So get those homemade planetcams out, send those pics in to Universe Today, and be sure to join in to the Virtual Star Party every Sunday Night… Saturn is sure to be featured!

The Return of Saturn: A Guide to the 2013 Opposition

A star party favorite is about to return to evening skies.

The planet Saturn can now be spied low to the southeast for northern hemisphere observers (to the northeast for folks in the southern) rising about 1-2 hours after local sunset this early April. That gap will continue to close until Saturn is opposite to the Sun in the sky later this month and rises as the Sun sets.

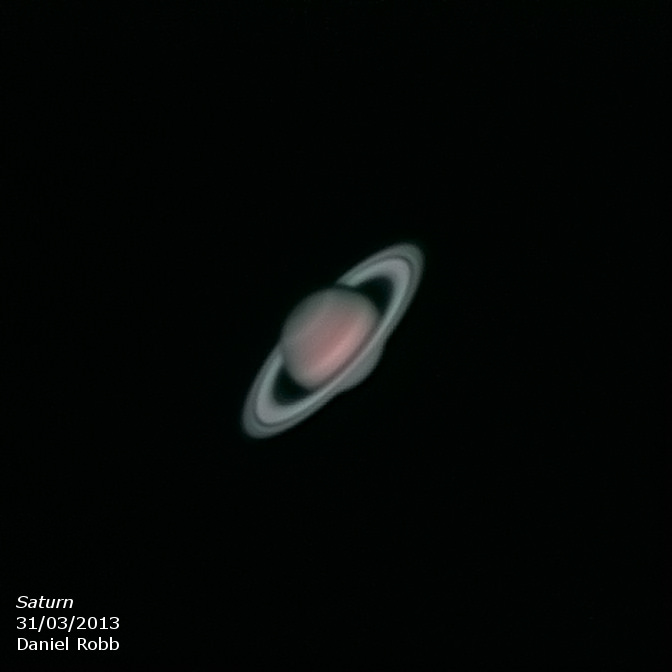

Opposition occurs on April 28th at 8:00 UT/4:00AM EDT. Saturn will shine at magnitude +0.1 and appear 18.8” in diameter excluding the rings, which give it a total angular diameter of 43”.

Saturn has just passed into the faint constellation Libra for 2013, although its springtime retrograde loop will bring it back into Virgo briefly. Both the 2013 and 2014 opposition will occur in Libra. Saturn will also pass 26’ from +4.2 Kappa Virginis on July 3rd as it moves back into Virgo while in retrograde before resuming direct motion back into Libra.

Saturn currently lies about 15° to the lower left of the +1.04 magnitude star Spica, also known as Alpha Virginis. Remember the handy saying to “Spike to Spica” from the handle of the Big Dipper asterism to locate the region. Another handy finder tip; stars twinkle, planet generally don’t. That is, unless your skies are extremely turbulent!

With an orbital period 29.46 years, Saturn moves slowly eastward year to year, taking 2-3 years to cross through each constellation along the ecliptic.

Oppositions are roughly 378 days apart and thus move forward on our calendar by about two weeks a year. Successive oppositions also move about 13° eastward per year.

Oppositions of the ringed planet are also currently becoming successively favorable for southern observers over the coming years. Saturn crossed into the southern celestial hemisphere some years back, and will be at its southernmost in 2018.

Saturn won’t pass north of the celestial equator again until early 2026. Saturn is 15 million kilometres farther from us than opposition last year as its moving toward aphelion in 2018.

Saturn will reach eastern quadrature this summer on July 28th and stand its highest south at sunset northern hemisphere observers. South of the equator, it will pass directly overhead or transit to the north. Saturn will be with us for most of the remainder of 2013 in evening skies until reaching solar conjunction on November 6th.

Looking at Saturn with binoculars, you’ll immediately note that something is amiss.

You’re getting a view similar to that of Galileo, who sketched Saturn as a sort of “double handled cup.” In fact, it wasn’t until 1655 that Christian Huygens correctly hypothesized that the rings of Saturn are a flat disk that is not physically in contact with the planet.

Huygens also discovered the large moon Titan. Shining at magnitude +8.5 and taking 16 days to orbit Saturn, Titan is the second largest moon in our solar system after Ganymede. Titan would easily be a planet in its own right if it orbited the Sun. Titan is easily picked out observing Saturn at low power through a telescope.

Observing Saturn at slightly higher magnification, five moons interior to Titan become apparent. From outside in, they are Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas. Exterior to Titan is the curious moon of Iapetus. Taking 79 days to complete one orbit of Saturn, Iapetus varies in brightness from magnitude +11.9 to +10.2, or a factor of over 5 times. Arthur C. Clarke placed the final monolith in the book adaptation of 2001: A Space Odyssey on Iapetus for this reason. Close-ups from the Cassini spacecraft reveal a two-faced world covered with a dark leading hemisphere and a bright trailing side, but alas, no alien artifacts.

But the centerpiece of observing Saturn through a telescope is its brilliant and complex system of rings. The A, B, and C rings are easily apparent through a backyard telescope, as is the large spacing known as the Cassini Gap.

The rings are also currently tilted in respect to our Earthly vantage point. The rings were edge-on in 2009 and vanish when this occurs every 15-16 years.

This year, we see the rings of Saturn at a respectable 19 ° opening and widening. The rings will appear at their widest at over 25° in 2017 and then become edge-on again in 2025.

The ring system of Saturn adds 0.7 magnitudes of overall brightness to the planet at opposition this year.

Another interesting optical phenomenon to watch for in the days leading up to opposition is known as the “opposition surge” in brightness, or the Seeliger effect. This is a retro-reflector effect familiar to many as high-beam headlights strike a highway sign. Think of the millions of particles making up Saturn’s rings as tiny little “retro-reflectors” focusing sunlight back directly along our line of sight. The opposition surge has been noted for other planets, but it’s most striking for Saturn when its rings are at their widest.

The disk of Saturn will cast a shadow straight back onto the rings around opposition and thus vanish from our view. The shadow across the back of the rings will then become more prominent over subsequent months, reaching its maximum angle at quadrature this northern hemisphere summer and then beginning to slowly slide back behind the planet again. A true challenge is to glimpse the disk of the through the Cassini gap in the rings… you’ll need clear steady skies and high magnification for this one!

It’s also interesting to note a very shallow partial lunar eclipse occurs with Saturn nearby just three days prior to opposition on April 25th. Saturn will appear 4° north of the Moon and it may be just possible to image both in the same frame.

Saturn takes about 30 years to make its way around the zodiac. I remember just beginning to observe Saturn will my new 60mm Jason refractor as a teenager in 1983 as it crossed the constellation Virgo.Hey, I’ve been into astronomy for over one “Saturnian year” now… where will the next 30 years find us?