We’re in the midst of a parade of planets crossing the evening sky. Jupiter reached opposition on May 9th, and sits high to the east at dusk. Mars heads towards a fine opposition on July 27th, nearly as favorable as the historic opposition of 2003. And Venus rules the dusk sky in the west after the setting Sun for most of 2018.

June is Saturn’s turn, as the planet reaches opposition this year on June 27th, rising opposite to the setting Sun at dusk.

In classical times, right up until just over two short centuries ago, Saturn represented the very outer limit of the solar system, the border lands where the realm of the planets came to an end. Sir William Herschel extended this view, when he spied Uranus—the first planet discovered in the telescopic era—slowly moving through the constellation Gemini just across the border of Taurus the Bull using a 7-foot reflector (in the olden days, telescopes specs were often quoted referring to their focal length versus aperture) while observing from his backyard garden in Bath, England on the night of March 13th, 1781.

Orbiting the Sun once every 29.5 years, Saturn is the slowest moving of the naked eye planets, fitting for a planet named after Father Time. Saturn slowly loops from one astronomical constellation along the zodiac to the next eastward, moving through one about every two years.

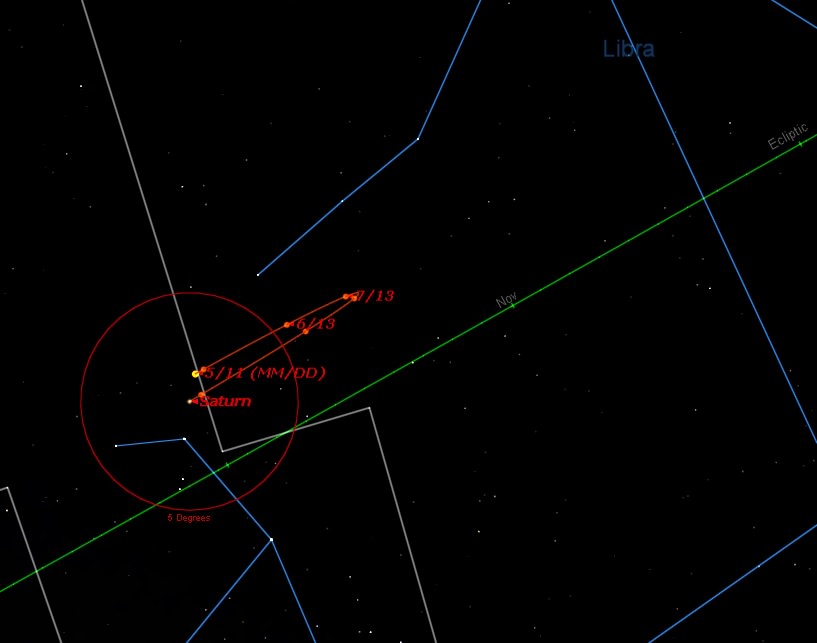

2018 sees Saturn in the constellation Sagittarius the Archer, just above the ‘lid’ of the Teapot asterism, favoring the southern hemisphere for this apparition. Saturn won’t cross the celestial equator northward again until 2026. Not that that should discourage northern hemisphere viewers from going after this most glorious of planets. A low southerly declination also means that Saturn is also up in the evening in the summertime up north, a conducive time for observing. Taking 29-30 years to complete one lap around the ecliptic as seen from our Earthly vantage point, Saturn also makes a great timekeeper with respect to personal life milestones… where were you back in 1989, when Saturn occupied the same spot along the ecliptic?

Saturn also shows the least variation of all the planets in terms of brightness and size, owing to its immense distance 9.5 AU from the Sun, and consequently 8.5 to 10.5 AU from the Earth. Saturn actually just passed its most distant aphelion since 1959 on April 17th, 2018 at 10.066 AU from the Sun.

Saturn’s in 2018 Dates with Destiny

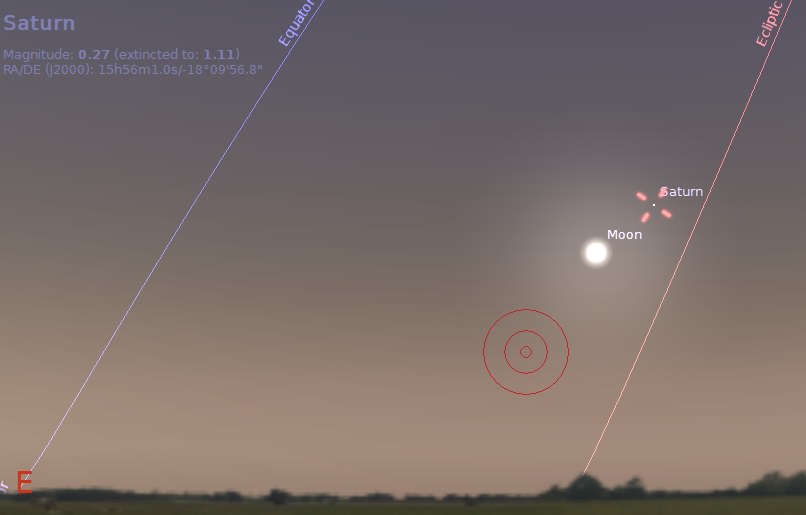

Saturn sits just 1.6 degrees south of the waning gibbous Moon tonight. The Moon will lap it again one lunation later on June 28th. Note that the brightest of the asteroids, +5.7 magnitude 4 Vesta is nearby in northern Sagittarius, also reaching opposition on June 19th. Can you spy Vesta with the naked eye from a dark sky site? 4 Vesta passes just 4 degrees from Saturn on September 23rd, and both flirt with the galactic plane and some famous deep sky targets, including the Trifid and Lagoon Nebulae.

Saturn reaches quadrature 90 degrees east of the Sun on September 25th, then ends its evening apparition when it reaches solar conjunction on New Year’s Day, 2019.

Saturn is well clear of the Moon’s path for most of this year, but stick around: starting on December 9th, 2018, the slow-moving planet will make a great target for the Moon, which will begin occulting it for every lunation through the end of 2019.

It’s ironic: Saturn mostly hides its beauty to unaided eye. Presenting a slight saffron color in appearance, it never strays much from magnitude -0.2 to +1.4 in brightness. One naked eye observation to watch for is a sudden spurt in brightness known as the opposition surge or Seeliger Effect. This is a retro reflector type effect, caused by all those tiny iceball moonlets in the rings reaching 100% illumination at once. Think of how the Full Moon is actually 3 to 4 times brighter than the 50% illuminated Quarter Moon… all those little peaks, ridges and crater rims no longer casting shadows do indeed add up.

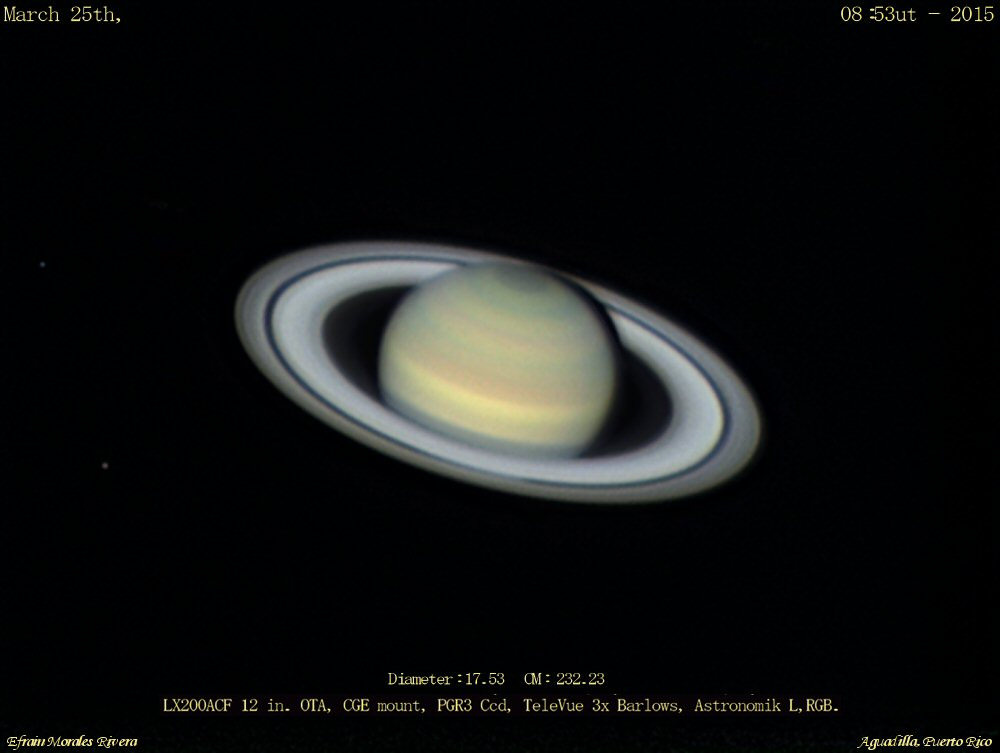

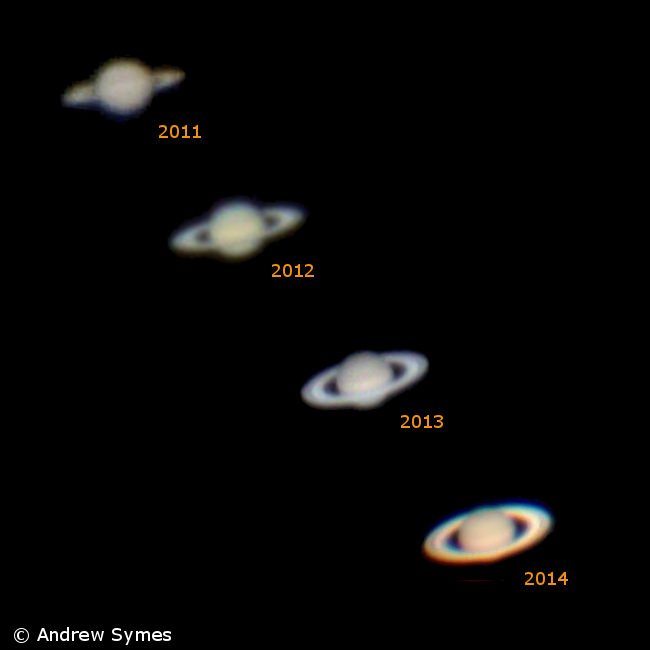

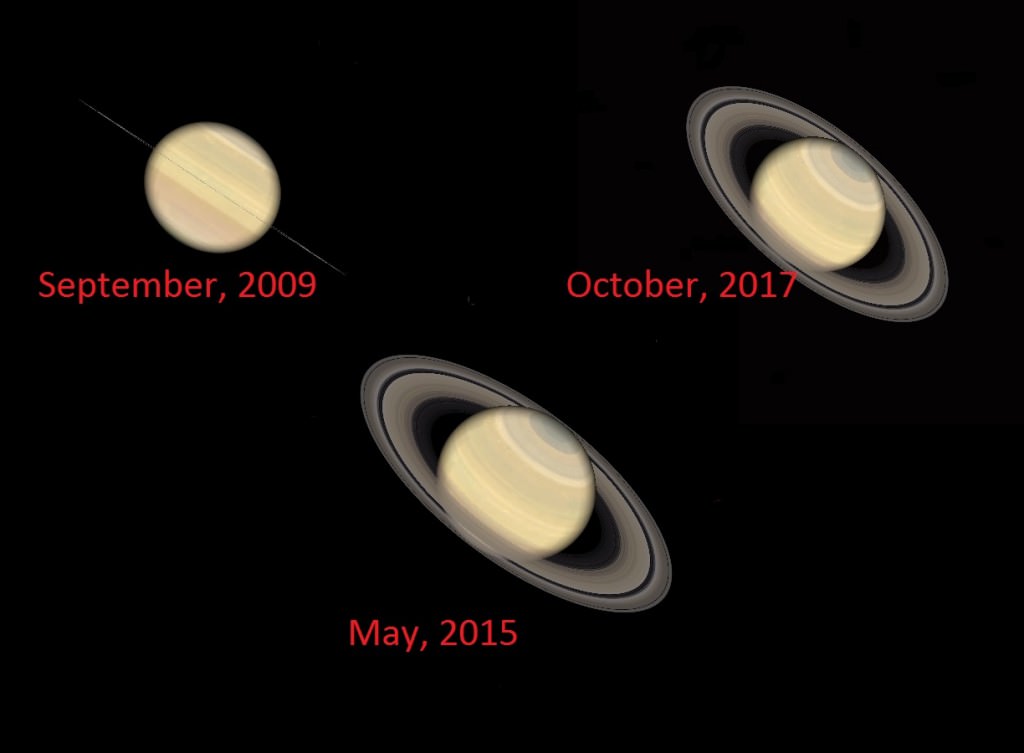

And this effect is more prominent in recent years for another reason: Saturn’s rings passed maximum tilt (26.7 degrees) with respect to our line of sight just last year, and are still relatively wide open in 2018. They’ll start slimming down again over the next few oppositions, reaching edge-on again in 2028.

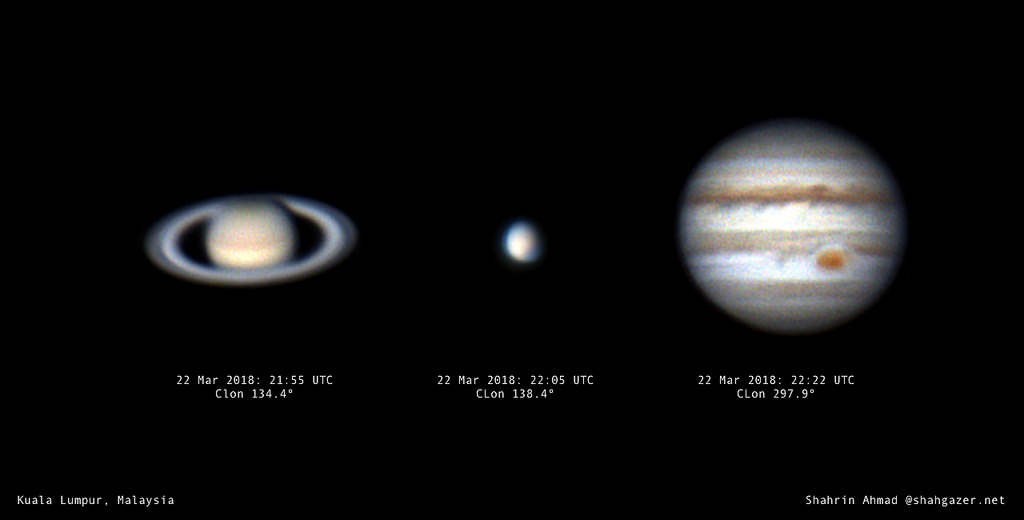

Even using a pair of 7×50 hunting binoculars on Saturn, you can tell that something is amiss. You’re getting the same view that Galileo had through his spyglass, the pinnacle of early 17th century technology. He could tell that something about the planet was awry, and drew sketches showing an oblong world with coffee cup handles on the side. Crank up the magnification using even a small 60 mm refractor, and the rings easily jump into view. This is what makes Saturn a star party staple, an eye candy feast capable of drawing the aim of all the telescopes down the row.

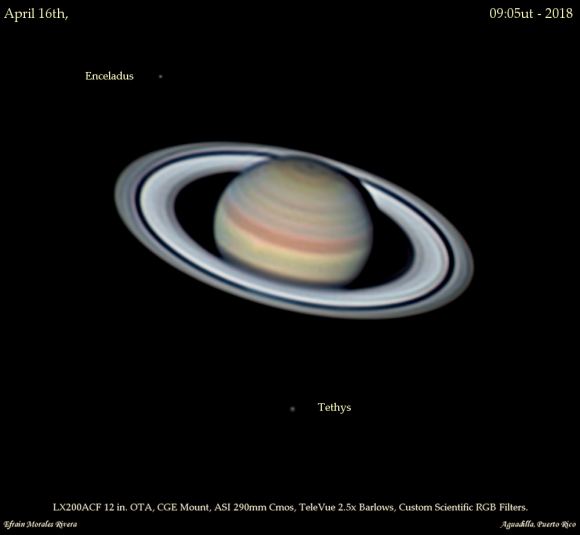

If seeing and atmospheric conditions allow, crank up the magnification up to 150x or higher, and the dark groove of the Cassini division snaps into view. Can you see the shadow of the disk of Saturn, cast back onto the plane of the rings? The shadow of the planet hides behind it near opposition, then becomes most prominent towards quadrature, when we get to peek around its edge. Can you spy the limb of the planet itself, through the Cassini Gap?

Though the disk of Saturn is often featureless, tiny swirls of white storms do occasionally pop up. Astrophotographer Damian Peach noted just one such short-lived storm on the ringed planet this past April 2018.

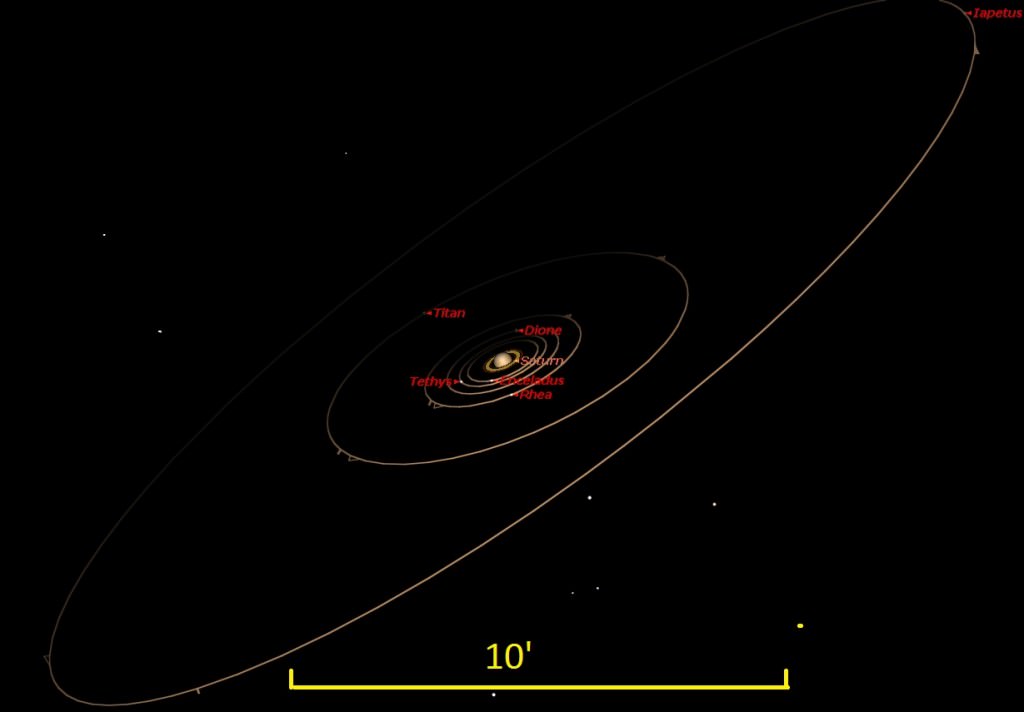

Saturn’s retinue of moons are also interesting to follow in there own right. The first one you’ll note is +8.5 magnitude smog-shrouded Titan. Larger in diameter than Mercury, Titan would easily be a planet in its own right, were it liberated from its primary’s domain.

Though Saturn has 62 known moons, only six in addition to Titan are in range of a modest backyard telescope: Enceladus, Rhea, Dione, Mimas, Tethys and Iapetus. Two-faced Iapetus is especially interesting to follow, as it varies two full magnitudes in brightness during its 79 day orbit. Arthur C. Clarke originally placed the final monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey on this moon, its artificial coating a beacon to astronomers. Today, we know from flybys carried out by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft that the leading hemisphere of Iapetus is coated with dark in-falling material, originating from the dark Phoebe ring around Saturn.

Owners of large light bucket telescopes may also want to try from two fainter +15th magnitude moons: Hyperion and Phoebe.

Fun fact: Saturn’s moons can also cast shadows back on the planet itself, much like the Galilean moons do on Jupiter… the catch, however, is that these events only occur around equinox season in the years around when Saturn’s rings are edge-on. This next occurs starting in 2026.

Cassini finished up its thrilling 20 year mission just last year, with a dramatic plunge into Saturn itself. It will be a while before we return again, perhaps in the next decade if NASA selects a nuclear-powered helicopter to explore Titan. Until then, be sure to explore Saturn this summer, from your Earthbound backyard.

Love to observe the planets? Check out our new forthcoming book, The Universe Today Ultimate Guide to Viewing the Cosmos – out on October 23rd, now up for pre-order.