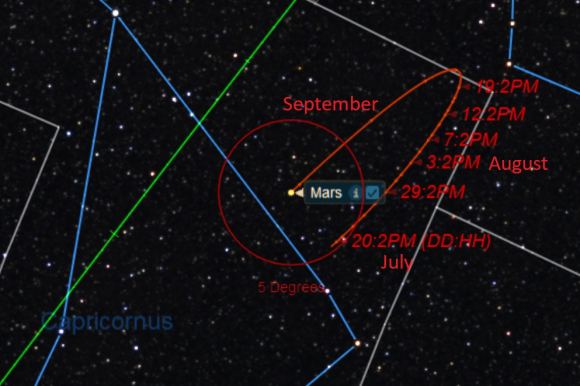

Have you checked out Mars this season? Mars reaches opposition on July 27th at 5:00 Universal Time (UT) shining at magnitude -2.8 and appearing 24.3” across—nearly as large as it can appear, and the largest since the historic opposition of 2003. We won’t have an opposition this favorable again until September 15th, 2035.

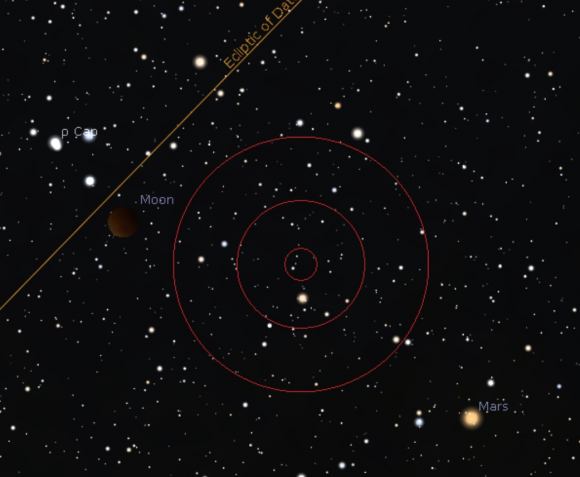

Mars starts this week near the +4th magnitude star Psi Capricorni, loops westward through retrograde briefly into the astronomical constellation of Sagittarius the Archer in late August before heading back into Capricornus in September.

Mars opened up 2018 just 4.8” across, trekking through the early dawn sky. What a difference a few months make: Mars broke 15” arc seconds—a maximum size for an unfavorable opposition near aphelion—on May 30th, and now dominates the summer sky around midnight.

There’s one downside, however, to the 2018 opposition of Mars: it’s occurring very nearly as far south along the ecliptic as it can. This is great news for observers in Australia, South Africa and South America, as the Red Planet rides high near the zenith at local midnight. Up north, however, we are still looking at Mars through the murk of the atmosphere lower to the horizon. For example, here in Norfolk, Virginia at latitude 37 degrees north, we never see Mars rise more than 29 degrees altitude above the southern horizon this season.

Down with Dust Storms

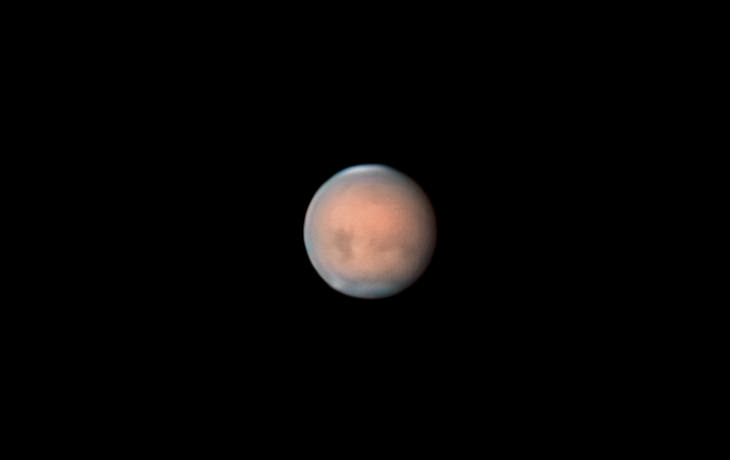

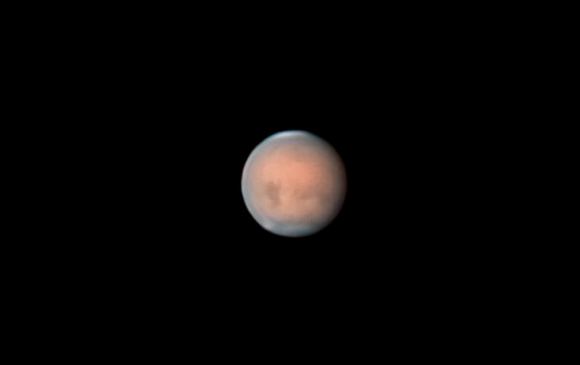

Does Mars seem a bit… peachy colored to you this season? It’s not your imagination: a planetary dust storm is indeed underway. It’s the middle of autumn for northern hemisphere of Mars, and this seems to be shaping up to be one of those oppositions where the planet, though at its closest, presents a featureless, dust-shrouded disk. This seems to be the case roughly every third opposition or so… our best hope now is that it may clear in the coming final weeks of July. We checked out Mars over the past weekend, and could just spy the pole cap and some slight detail under a veil of haze.

Despite the depiction of Martian dust storms in science fiction blockbusters such as The Martian as furious and unrelenting, these storms are actually pretty mild-mannered, barely able to chase a leaf before them through the tenuous Martian atmosphere, if deciduous trees grew on Mars. One thing Martian dust storms can do, however, is coat solar panels with a battery-killing film, and it has yet to be seen if the aging Opportunity rover will awaken and phone home from Meridiani Planum.

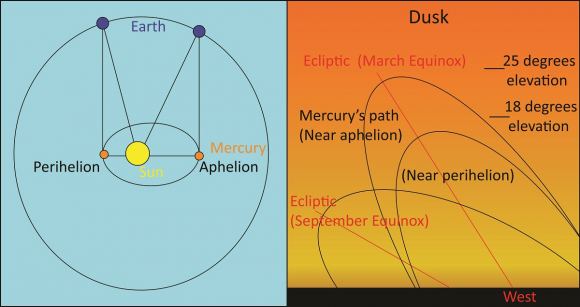

Unlike the Earth, Mars has a markedly elliptical orbit, varying from 1.7 (AU) astronomical units from the Sun at aphelion to 1.4 AU near perihelion. This all means that not every opposition of Mars is equal; in fact, Mars can range from 55 million to 102 million kilometers from the Earth near opposition and appear 13.8” to 25.1” across, depending on where it’s at in its orbit. And although Mars laps the Earth roughly every 26 months, a cycle of favorable oppositions repeat every 15 years.

In 2018, Mars reaches opposition on July 27th at 5:00 UT/1:00 AM EDT 57.8 million kilometers from the Earth, then makes its closest approach four days later on July 31st at 8:00 UT/4:00 AM EDT, 57.6 million kilometers distant. Why the discrepancy? Well, opposition is simply reckoned as the point where an outer planet reaches an ecliptic longitude of 180 degrees opposite from the Sun. Mars, however, is still headed inward towards perihelion on September 16th, while Earth just came off of aphelion on July 6th.

Visually, Mars can on occasion “go yellow” and present a saffron color even to the naked eye if a planetary wide sandstorm is underway. At the eyepiece, the most prominent feature is always the pole cap, a white dollop on the planet’s pumpkin hued limb. Crank up the magnification, and dark patches come into view, as Mars is the only planet in the solar system presenting an actual surface available for amateur scrutiny. Mars has a day very similar to Earth’s at only 37 minutes longer in duration, meaning that if you observe Mars at the same time every evening, you’ll see nearly the same longitude of the planet turned towards you, shifted 10 degrees westward. A great tool for comparing what features on Mars are currently turned Earthward is Mars Previewer.

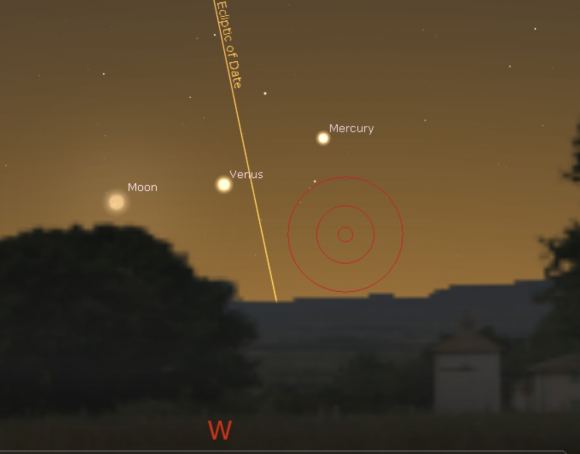

Can you spy Mars… daytime? This month is a good time to try, as it currently shines brighter than Jupiter. The easiest thing to do is lock on to it with a telescope near dawn as it sets to the west and the Sun rises in the east, then simply track it into the daytime sky. We’ve seen Mars in 2003 and again this year while the Sun is still above the horizon… having the Moon nearby also helps, though of course, Mars is very close to the horizon at sunset/sunrise right at opposition.

And speaking of which, viewers in Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia are in for a special treat on the evening of July 27th, as a total eclipse of the Moon occurs just 15 hours after Mars passes opposition. Ironically, this is also a Minimoon eclipse, as the Moon also passes apogee just 14 hours prior to entering the Earth’s shadow. Expect to see the Red Planet just seven degrees from the blood red Moon at mid-eclipse (more on the eclipse next week).

The Moon won’t occult (pass in front of) Mars again until November 16th, 2018 for the very southernmost tip of South America. Stick around until July 26th, 2344 AD, and you can witness the Moon occulting the planet Saturn during an eclipse, though you’ll have to journey to southern Japan to do it.

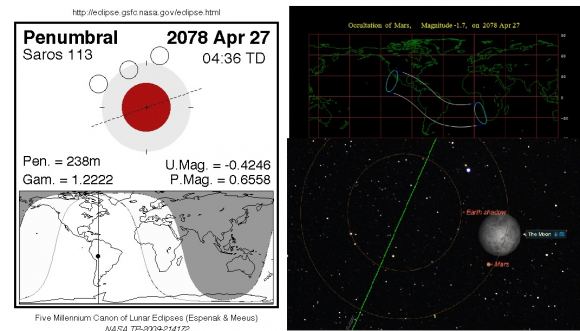

But you may not have to wait that long… stick around until April 27th, 2078, and you can witness the Moon occult Mars… during a penumbral lunar eclipse:

This current evening apparition of Mars ends over a year from now on September 2nd, 2019, as Mars reaches solar conjunction on the farside of the Sun.

Finally, opposition is a great time to try and check the tiny Martian moons Phobos and Deimos off of your life list. These two moons were actually discovered by Asaph Hall from the United States Naval Observatory’s newly installed 26-inch refractor during a favorable parihelic apparition of Mars in 1877.

Shining at magnitude +12.4 (Deimos) and +11.3 (Phobos), seeing these moons would be a cinch… were it not for the presence of Mars shining a million times brighter nearby. Your best bet is to construct an occulting bar eyepiece (we’ve used a thin strip of foil and a guitar string affixed to an eyepiece to accomplish this) or simply place brilliant Mars just out of view. Phobos orbits once every 7.7 hours and substends 20” from the disk of Mars, while Deimos goes around Mars once every 30.35 hours and journeys 66” with each elongation from the Martian disk. PDS rings node or a good planetarium program such as Starry Night or Stellarium will show the current orientation of the Martian moons, aiding in your decision of whether or not to take up the quest.

Don’t miss out on Mars this opposition season… it’ll be almost another two decades before we get another favorable view.

Read all about viewing the planets, from observation to imaging and sketching in our new book: The Universe Today Guide to the Cosmos out October 23rd, now available for pre-order.