You could be forgiven for thinking this summer that the “supermoon” is now a monthly occurrence. But this coming weekend’s Full Moon is indeed (we swear) the closest to Earth for 2014.

What’s going on here? Well, as we wrote one synodic month ago — the time it takes for the Moon to return to the same phase at 29.5 days — we’re currently in a cycle of supermoons this summer. That is, a supermoon as reckoned as when the Full Moon falls within 24 hours of perigee, a much handier definition than the nebulous “falls within 90% of its orbit” proposed and popularized by astrologers.

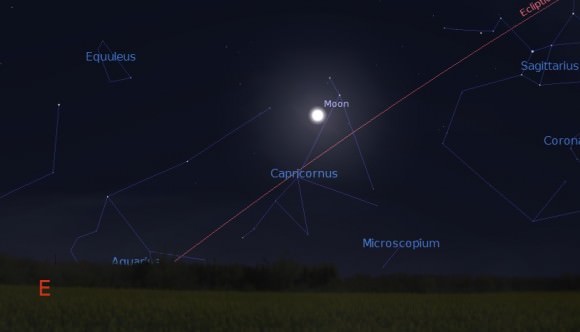

The supermoons for 2014 fall on July 13th, August 10th and September 8th respectively. You could say that this weekend’s supermoon is act two in a three act movement, a sort of Empire Strikes Back to last month’s A New Hope.

Now for the specifics: Full Moon this weekend occurs on August 10th at 18:10 Universal Time (UT) or 2:10 PM EDT. The Moon will reach perigee or its closest point to the Earth at 17:44 UT/1:44 PM EDT just 26 minutes prior to Full, at 55.96 Earth radii distant or 356,896 kilometres away. This is just under 500 kilometres shy of the closest perigee that can occur at 356,400 kilometres distant. Perigee was closer to Full phase time-wise last year on June 23rd, 2013, but this value won’t be topped or tied again until November 25th, 2034. The Moon will be at the zenith and closest to the surface of the Earth at the moment it passes Full over the mid-Indian Ocean on Sunday evening nearing local midnight.

Now for a reality check: The August lunar perigee only beats out the January 1st approach of the Moon for the closest of 2014 by a scant 25 kilometres. Perigees routinely happen whether the Moon is Full or not, and they occur once every anomalistic month, which is the average span from perigee-to-perigee at 27.6 days. This difference between the anomalistic and synodic period causes the coincidence that is the supermoon to precess forward about a month a year. You can see our list of supermoon seasons out until 2020 here.

And don’t forget, the Moon actually approaches you to the tune of about half of the radius of the Earth while it rises to the zenith, only to recede again as it sinks back down to the horizon. The rising Full Moon on the horizon only appears larger mainly due to an illusion known as the Ponzo Effect.

The apparent size of the Moon varies about 14% in angular diameter from 29.3′ (known as an apogee “mini-Moon”) to 34.1′ at its most perigee “super-size” as seen from the Earth.

Astronomers prefer the use of the term Perigee Full Moon, but the supermoon meme has taken on a cyber-life of its own. Of course, we’ve gone on record before and stated that we prefer the more archaic term Proxigean Moon, but the supermoon seems here to stay.

And as with many Full Moon myths, this week’s supermoon will be implicated in everything from earthquakes to lost car keys to other terrestrial woes, though of course no such links exist. Coworkers/family members/strangers on Twitter will once again insist it was “the biggest ever,” and claim it took up “half the sky” as they unwittingly take part in an impromptu psychological perception test.

Fun fact: you could ring local the horizon with 633 supermoons!

And of course, many a website will recycle their supermoon posts, though of course not here at Universe Today, as we bake our science fresh daily.

So what can you expect? Well, a perigee Full Moon can make for higher than usual tides. New York City residents had the bad fortune of a Full Moon tidal surge in 2012 when Hurricane Sandy made landfall. Though there doesn’t seem to be a chance for a repeat of such an occurrence in 2014 in the Atlantic, super-typhoon Halong is churning towards the Japanese coastline for landfall this weekend…

Observationally, Full Moon is actually a lousy time for astronomical observations, causing many a deep sky astrophotographer to instead stay home and visit the family, while lurking astrophotography forums and debunking YouTube UFO videos.

Pro-tip: want your supermoon photo/video to go viral? Shoot the rising Moon just the evening prior when it’s waxing gibbous but nearly Full. Not only will it be more likely to be picked up while everyone is focused on supermoon lunacy, but you’ll also have the added bonus of catching the Moon silhouetted against a low-contrast dusk sky. We have a pre-supermoon rising video from a few years back that still trends with each synodic period!

Well, that’s it ‘til September, when it’ll be The Return (Revenge?) of the Supermoon. Be sure to send those pics in to Universe Today’s Flickr forum, you just might make the supermoon roundup!