[/caption]

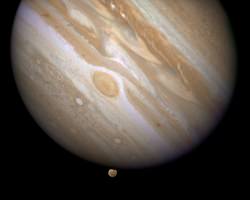

Advances in technology have lead to the discovery of new planets outside of our Solar System, and now even new moons in our own backyard.

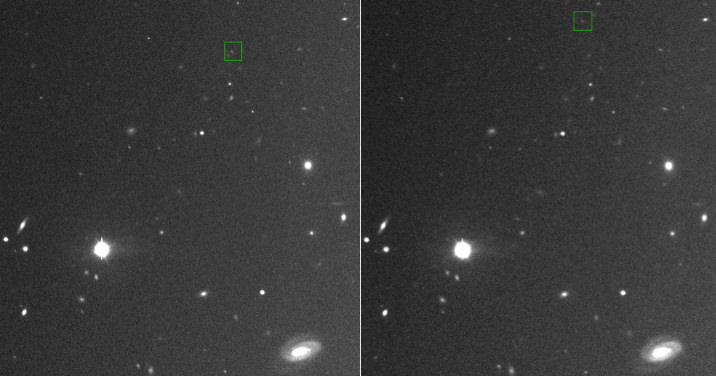

Last September, two satellites – the smallest ever discovered – were found orbiting Jupiter.

That brings the number of Jovian moons to a whopping 66. The moons – each about 1 km in size – are very distant from Jupiter. It takes the tiny satellites 580 and 726 days to orbit the gas giant.

The discovery could lead us one step closer to understanding the formation and evolution of our solar system. At least that’s the hope of Scott Sheppard, who works at the the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution of Science in Washington, D.C. It was Sheppard who, with the help of the massive Magellan telescope at Las Campanas, Chile, initially observed the moons.

“The new satellites are part of the outer retrograde swarm of objects around Jupiter. It is likely there are about 100 satellites of this size around Jupiter,” Sheppard said, explaining that Magellan has made it easier to detect objects further away from Earth. “Up until the last decade, the technology wasn’t there to discover these things because they are very small and very faint.”

The two tiny, irregular moons are called S/2011 J1 and S/2011 J2. Thankfully, those names aren’t expected to stick. Once officially confirmed (Sheppard expects it to happen this year), he will have the opportunity to name each. But, Sheppard can’t pick just any moniker. The names, according to the International Astronomical Union, must be related to Jupiter or Zeus, the Roman and Greek mythological figures who served as king of the gods.

Maybe that’s why Sheppard hasn’t yet thought of any names for the soon-to-be members of the Jovian moon list. Are there any names that haven’t already been chosen? Europa, Thebe, Io, Callisto, Sinope, Ganymede …

Naming requirements will definitely need to change because, as Sheppard explains, there are a lot more moons to discover around some of our other gas – and ice – giants.

“There are a similar amount of objects orbiting Saturn and Neptune, which are more distant from the Sun,” Sheppard said, citing a survey of the sky conducted by the Carnegie Institution of Washington in the early 2000s. “If larger telescopes are built in the future, we’ll be able to discover more of these objects and find out what the objects are like,” Sheppard said.

And finding more of these smaller, distant, irregular satellites is a key to understanding our past.

Here’s why: Irregular satellites are believed to have been captured by their respective planets because the moons typically orbit in the opposite direction of the planet’s rotation, and, they also have eccentric and highly inclined orbits.

Those types of moons differ from regular satellites, which are believed to have formed from the same materials that comprise the planet. That’s because the moons tend to have nearly circular orbits, and, they orbit their respective planets in the same direction that the planet rotates.

A planet can temporarily capture an object, i.e. Shoemaker-Levy 9, but in the present time, “a planet has no known efficient mechanism to permanently capture satellites. Thus, outer satellite capture must have occurred near the time of planet formation when the Solar System was not as organized as it is now,” Sheppard said.

“The orbital history of a satellite can be very complex … but understanding where a satellite came from can tell us about the formation and evolution of our Solar System.”

Click here to learn more about the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. For more information about Jovian moons, go to Scott Sheppard’s Jupiter Satellite Page.