Have YOU seen all 110?

The passage of the northward equinox last week on March 20th means one thing in the minds of many a backyard observer: the start of Messier Marathon season. This is a time of year during which a dedicated observer can conceivably spot all of the objects in Charles Messier’s famous deep sky catalog in the span of one night.

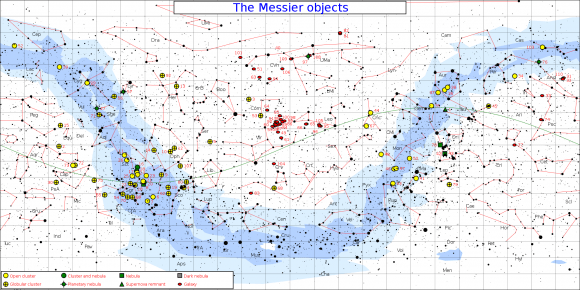

We’ve written about some tips and tricks to completing this challenge previously, as well as the optimal dates for carrying a marathon out. Typically, the New Moon weekend nearest the March equinox is the best time of year for northern hemisphere observers to target all of the objects on Messier’s list. This works because a majority of the Messier objects are clustered into two regions: towards the core of our galaxy in Sagittarius — where the Sun sits during the December solstice — up through the summer triangle constellations of Cygnus, Aquila and Lyra, and in the bowl of Virgo asterism and its super cluster of galaxies that extends northward into the constellation of Coma Berenices. In March through early April the Sun sits in the constellation of Pisces, well away from the galactic plane.

The prospects for completing a Messier marathon in 2014 favor the last weekend on March on the 29th-30th. The Moon reaches New on Sunday, March 30th at 18:45 Universal Time/2:45 PM EDT.

Messier marathons first came into vogue in the early 1970s right around the time Schmidt-Cassegrain and large Dobsonian “light bucket” telescopes came into general use.

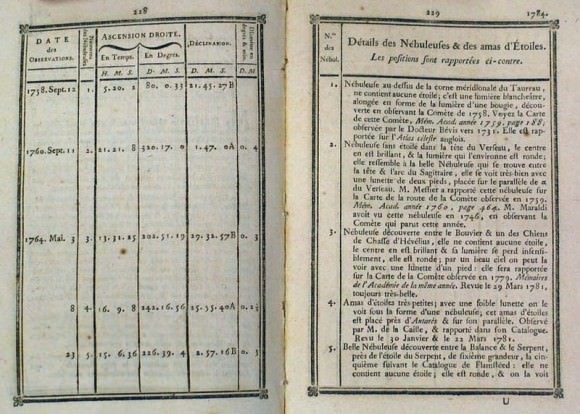

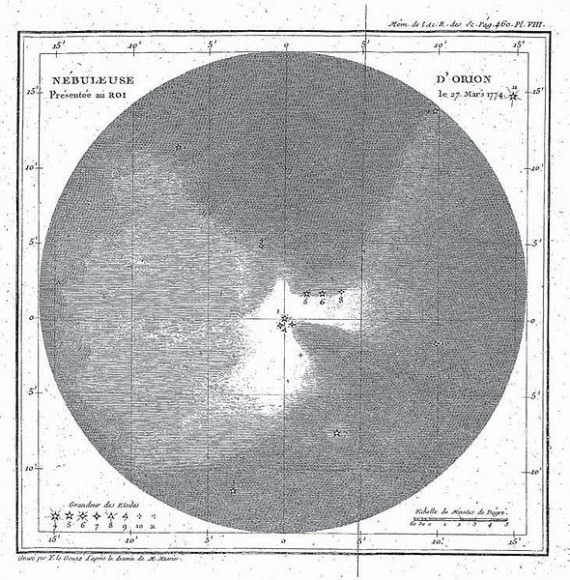

Charles Messier began noting the curious objects that he would later incorporate into his famous catalog during the summer of 1758, with his description of the Crab Nebula in Taurus, which would become Messier object number one or M1. Messier was a prolific comet hunter and discovered 21 comets in his lifetime. The catalog was compiled over the span of 13 years from 1771 to 1784. Messier’s original list contained 45 objects, and was later expanded in subsequent editions 103, with Messier’s assistant Pierre Méchain adding six more objects to the catalog. The list is generally tallied at 110 objects, with one famous controversy being M102, which is generally cited as a re-observation of M101 or the galaxy NGC 5866.

The catalog itself contains a grab bag of open and globular clusters, galaxies, planetary and diffuse nebulae, and one double star (M40). The Messier catalog spans the sky down to M7, an object also known as the Ptolemy Cluster, which is the southernmost object on the list at latitude -34 degrees 48’ south.

Messier observed from Paris at latitude +48 degrees 51’ north using two primary telescopes of the almost one dozen that he owned for his discoveries: a 6.4” Gregorian reflector and a 3.5” refractor. Messier knew nothing of the nature of these “faint fuzzies” that he’d periodically stumbled across in his cometary vigil. His original intent was to compile a list of “comet imposters” in the night sky for comet hunters to be aware of in their quests. In his words:

“What made me produce this catalog was the nebula which I had seen in Taurus while I was observing the comet of that year (1758). The shape and brightness of that nebula reminded me so much of a comet, that I undertook to find more of its kind, to save astronomers from confusing these nebulae with comets.”

“Beware, here doth not lie comets,” Messier admonishes future generations of observers. Still, some peculiarities remain in the catalog: why did Messier, for example, include such obvious “non-comets” as the Pleiades (M45), but skip over the brilliant Double Cluster in Perseus?

Alas, such mysteries are known only to Messier, who was interred at the famous Père Lachaise cemetery after his death in 1817. When we visit Paris, we’ll bypass Jim Morison to leave a copy of Burnham’s Celestial Handbook at Messier’s grave.

And just like the road variety, “running the Messier marathon” takes all of the stamina and pacing that a visual athlete can muster. You’ll want to grab M77 and M74 immediately after dusk, or the marathon will be over before it starts. From there, move on up north to the famous Andromeda galaxy (M31) and the scattering of objects around it before settling in for a more leisurely observing pace moving westward through the constellations of Orion, Leo and surrounding objects.

Now towards the approach of local midnight comes the first large group: the Virgo cluster of galaxies extending through Coma Berenices, rising to the east. After this batch, you can catch some quick shut-eye before bagging the Messier objects towards the galactic center and up through Cygnus in the pre-dawn. Plan ahead; M52, M2 and M30 are especially notoriously difficult in the spring dawn sky!

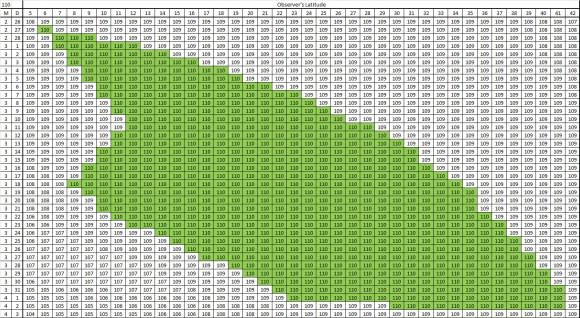

It’s also worth noting your “attitude versus latitude” plays a role as well. To this end, Ed Kotapish compiled this nifty perpetual chart of when the entire Messier catalog is visible from respective latitudes:

“The bounds of the chart are for a variety of objects,” Ed told Universe Today. “I used nautical twilight (when the Sun falls below -12 degrees in elevation) as the starting and ending condition.” Ed also notes that the top curve of the chart on the morning side is bounded by the difficulty in finding troublesome M30, while the left bottom evening boundary is limited by the observability of M110 and M74, which can be a problem for observers at higher latitudes.

Alternate versions of the Messier marathon exist as well, such as imaging or even sketching all 110 objects in one night.

Why complete a Messier marathon? Well, not only does such a feat hone your visual skills as an observer, but it also familiarizes you with the entire catalog… and there’s nothing that says you have to complete it all in one evening, except of course, for bragging rights at the next star party!

Good luck!

-Here’s a handy list of all 110 of the Messier objects in the catalog.

-Be sure to send those pics of Messier objects and more in to Universe Today’s Flickr forum!