An international team of scientists has discovered an enormous wave of hot gas rolling its way through the Perseus galaxy cluster. The wave is a giant version of what’s called a Kelvin-Helmholtz wave. They’re created when two fluids intersect at different velocities: for example, when wind blows over water.

In this instance, the wave was caused by a small galaxy cluster grazing the Perseus cluster, and setting off a chain of events lasting billions of years. The findings appear in a paper in the June 2017 issue of the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

“The wave we’ve identified is associated with the flyby of a smaller cluster, which shows that the merger activity that produced these giant structures is still ongoing.” – Stephen Walker, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

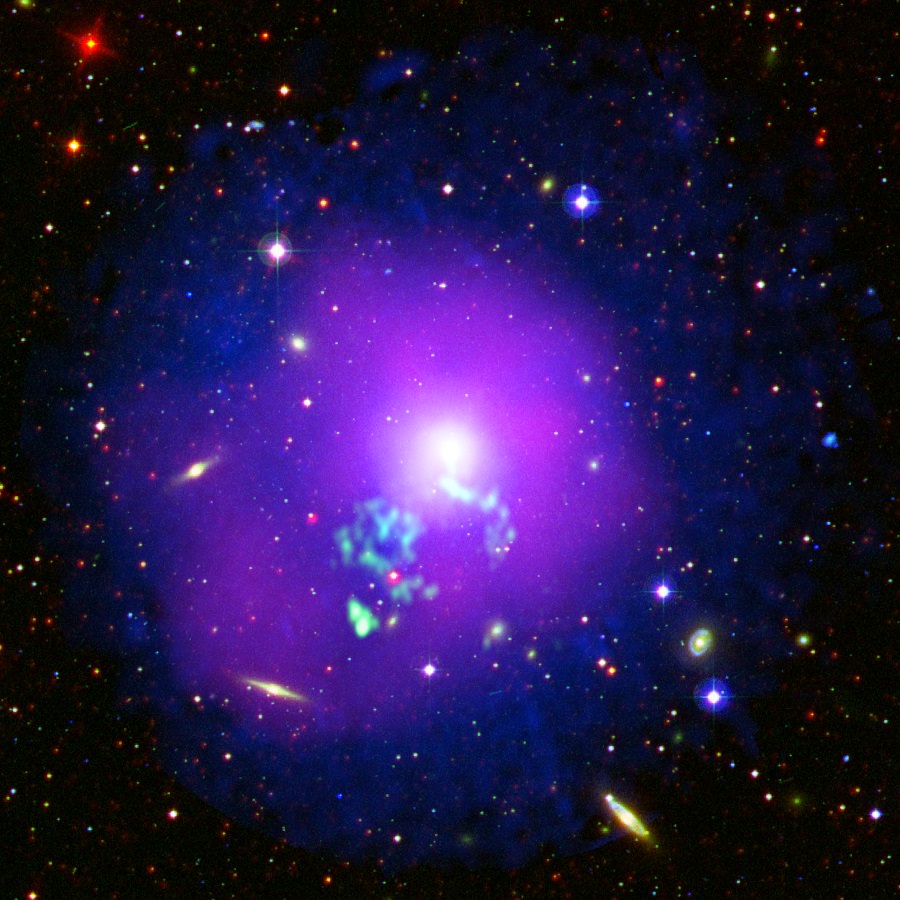

“Perseus is one of the most massive nearby clusters and the brightest one in X-rays, so Chandra data provide us with unparalleled detail,” said lead scientist Stephen Walker at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The wave we’ve identified is associated with the flyby of a smaller cluster, which shows that the merger activity that produced these giant structures is still ongoing.”

The Perseus galaxy cluster, also known as Abell 426, is 240 million light years away, and is about 11 million light years across. It’s one of the most massive objects we know of, and it’s named after the Perseus constellation, which appears in the same part of the sky.

Galaxy clusters are the largest gravitationally-bound objects in the Universe. Most of the observable matter in galaxy clusters is gas. But the gas is super hot—tens of millions of degrees hot—which means it emits x-rays.

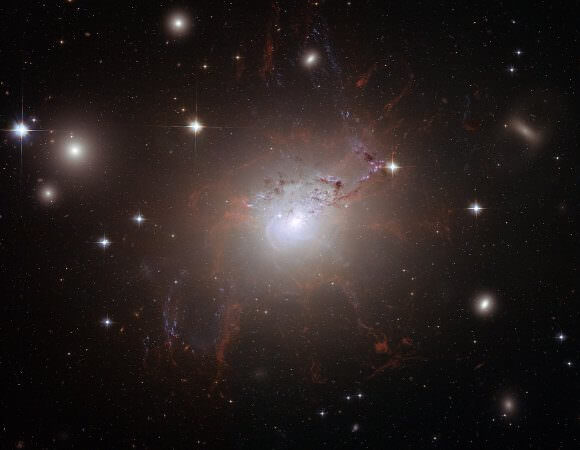

X-Ray observations of Perseus have revealed several features and structures in the gas structure of the cluster. Some of them are bubble-like features caused by the super-massive black hole (SMBH) in NGC 1275, the Perseus cluster’s central galaxy. Another of these features is known as “the bay.” The bay is a concave feature which couldn’t have been formed by the SMBH.

The bay is a puzzle because it doesn’t produce any emissions, which would be expected of something formed by a SMBH. The bay also doesn’t conform to models of how gas should behave in this situation.

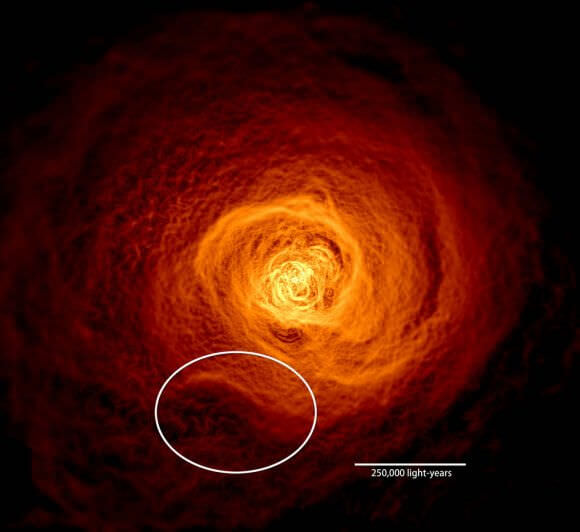

The lead scientist behind the study is Stephen Walker at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Walker turned to the Chandra X-ray Observatory to help solve this puzzle. Existing Chandra images of the Perseus cluster were filtered in order to highlight the edges of structures, and to make any subtle details more visible.

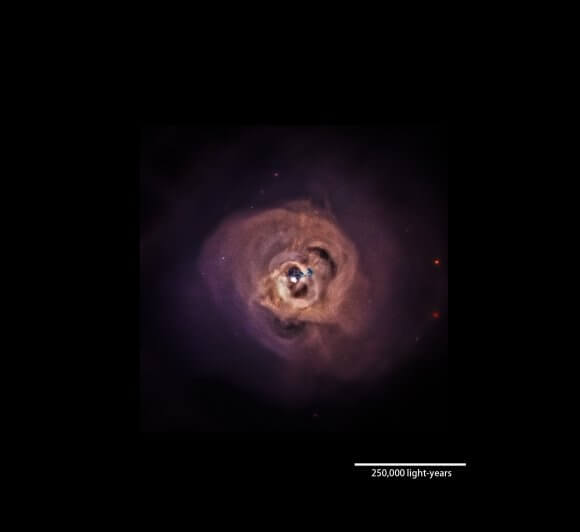

These filtered and processed images were then compared to computer simulations of galaxy clusters merging. John ZuHone, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, has created an online catalog of these simulations.

“Galaxy cluster mergers represent the latest stage of structure formation in the cosmos.” -John ZuHone, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

“Galaxy cluster mergers represent the latest stage of structure formation in the cosmos. Hydrodynamic simulations of merging clusters allow us to produce features in the hot gas and tune physical parameters, such as the magnetic field. Then we can attempt to match the detailed characteristics of the structures we observe in X-rays.” -John ZuHone, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

One of the simulations matched what astronomers were seeing in Perseus. In it, a large cluster like Perseus had settled itself into two regions: a colder region of gas around 30 million degrees Celsius, and a hotter region of gas at almost 100 million degrees Celsius. In this model, a cluster smaller than Perseus, but about a thousand times more massive than the Milky Way passes close to Perseus, missing its center by about 650,000 light years.

That happened about 2.5 billion years ago, and it set off a chain of events still playing itself out.

The near miss caused a gravitational disturbance that created an expanding spiral of the colder gas. An enormous wave of gas has formed at the edge of the spiral of colder gas, where it intersects with the hotter gas. This is the Kelvin-Helmholtz wave seen in the images.

“We think the bay feature we see in Perseus is part of a Kelvin-Helmholtz wave, perhaps the largest one yet identified, that formed in much the same way as the simulation shows,” Walker said. “We have also identified similar features in two other galaxy clusters, Centaurus and Abell 1795.”

The study provided another benefit besides just spotting an impossibly enormous wave. It allowed the team to measure the magnetic properties of the Perseus cluster. The researchers discovered that the strength of the magnetic field in the cluster affected the size of the wave of gas. It the field is too strong, the waves don’t form at all, and if the magnetic field is too weak, then the waves would be even larger.

According to the team, there is no other known way to measure the magnetic field.

Source: Scientists Find Giant Wave Rolling Through the Perseus Galaxy Cluster