[/caption]

As a professional astronomy journalist, I read a lot of science papers. It hasn’t been all that long ago that I remember studying about galaxy groups – with the topic of dark matter and dwarf galaxies in particular. Imagine my surprise when I learn that two of my friends, who are highly noted astrophotographers, have been hard at work doing some deep blue science. If you aren’t familiar with the achievements of Ken Crawford and R. Jay Gabany, you soon will be. Step inside here and let us tell you why “it matters”…

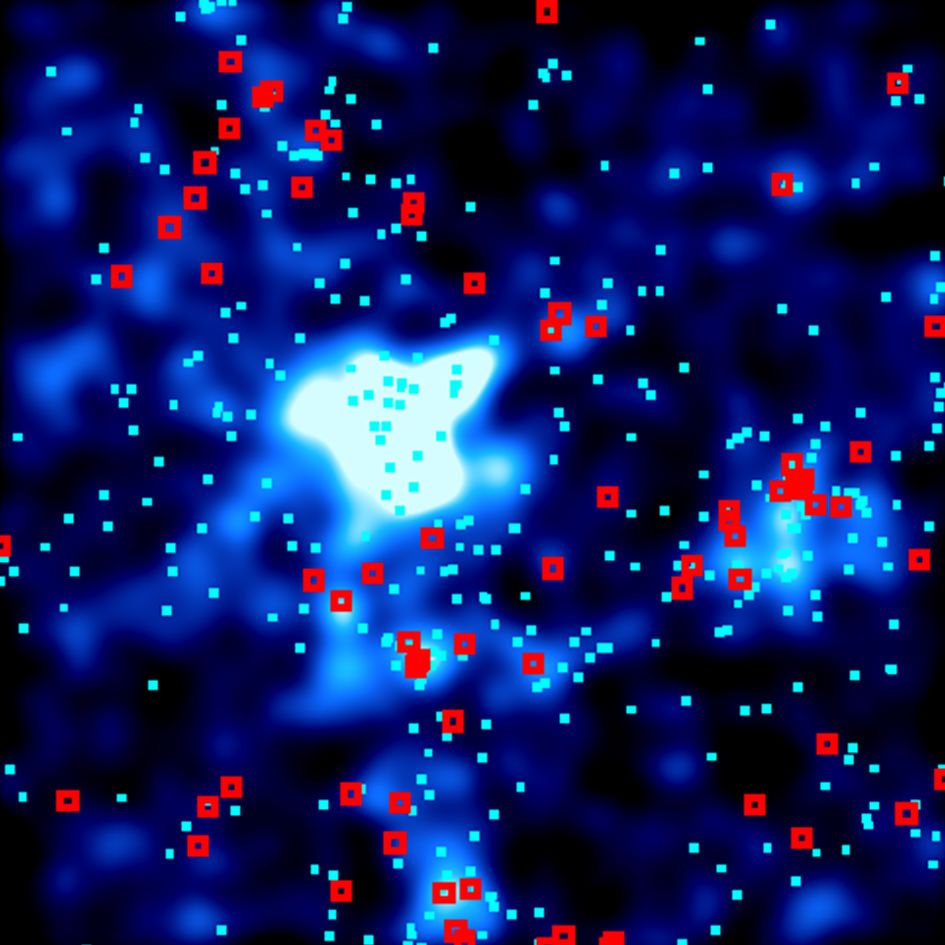

According to Ken’s reports, Cold Dark Matter (or CDM) is a theory that most of the material in the Universe cannot be seen (dark) and that it moves very slowly (cold). It is the leading theory that helps explain the formation of galaxies, galaxy groups and even the current known structure of the universe. One of the problems with the theory is that it predicts large amounts of small satellite galaxies called dwarf galaxies. These small galaxies are about 1000th the mass of our Milky Way but the problem is, these are not observed. If this theory is correct, then where are all of the huge amounts of dwarf galaxies that should be there?

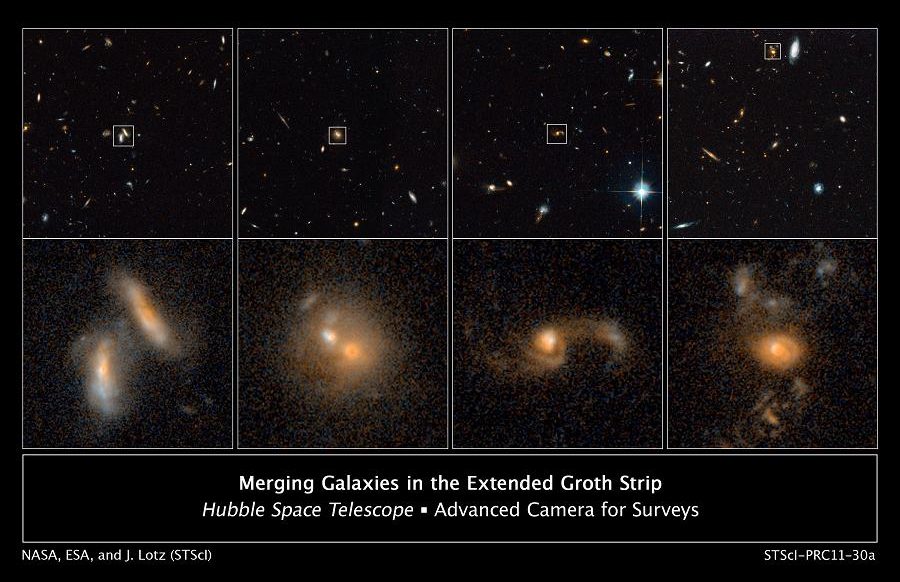

Enter professional star stream hunter, Dr. David Martinez-Delgado. David is the principal investigator of the Stellar Tidal Stream Survey at the Max-Planck Institute in Heidelberg, Germany. He believes the reason we do not see large amounts of dwarf galaxies is because they are absorbed (eaten) by larger galaxies as part of the galaxy formation. If this is correct, then we should find remnants of these mergers in observations. These remnants would show up as trails of dwarf galaxy debris made up mostly of stars. These debris trails are called star streams.

“The main aim of our project is to check if the frequency of streams around Milky Way-like galaxies in the local universe is consistent with CDM models similar to that of the movie.” clarifies Dr. Martinez-Delgado. “However, the tidal destruction of galaxies is not enough to solve the missing satellite problem of the CDM cosmology. So far, the best given explanation is that some dark matter halos are not able to form stars inside, that is, our Galaxy would surround by a few hundreds of pure dark matter satellites.”

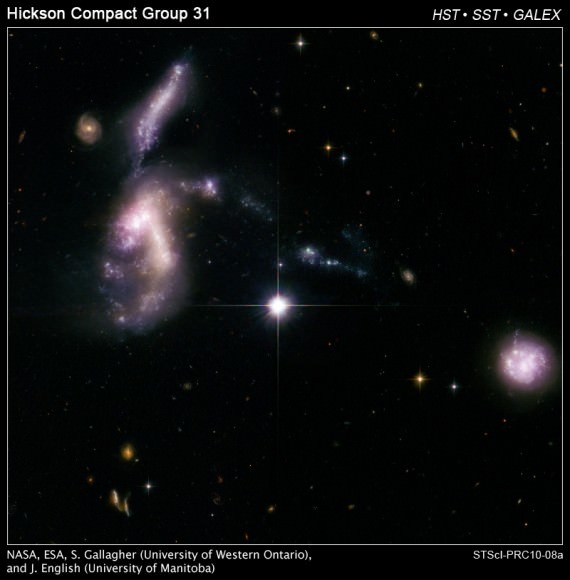

Enter the star stream hunters professional team. The international team of professional astronomers led by Dr. David Martinez-Delgado has identified enormous star streams on the periphery of nearby spiral galaxies. With deep images he showed the process of galactic cannibalism believed to be occurring between the Milky Way and the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. This is in our own back yard! Part of the work is using computer modeling to show how larger galaxies merge and absorb the smaller ones.

Enter the team of amateurs led by R. Jay Gabany. David recruited a small group of amateur astrophotographers to help search for and detect these stellar fossils and their cosmic dance around nearby galaxies, thus showing why there are so few dwarf galaxies to be found.

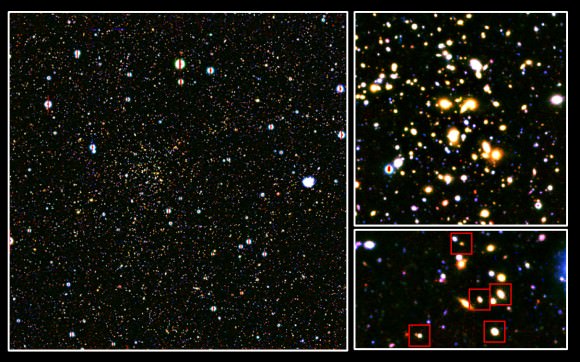

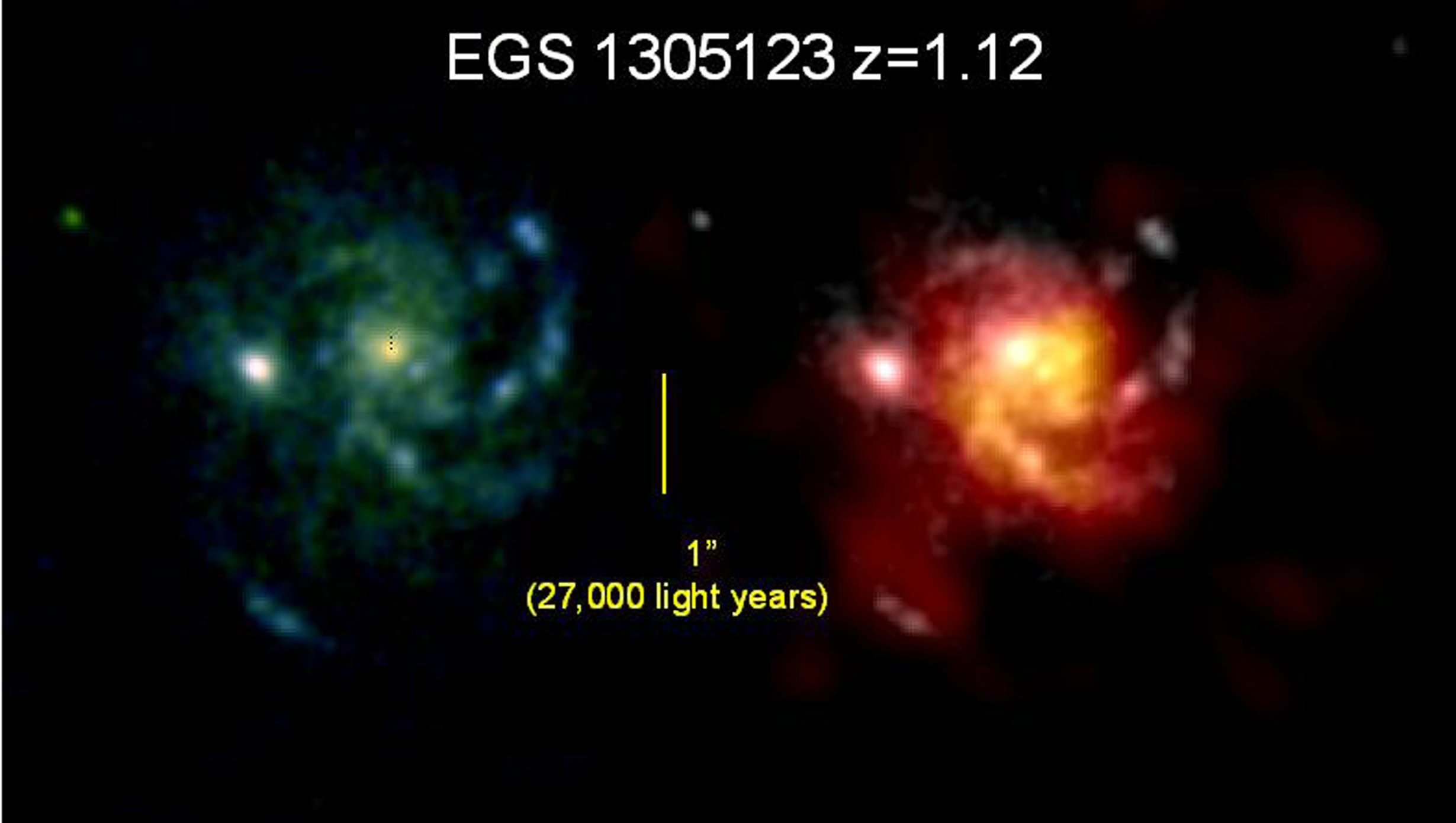

“Our observations have led to the discovery of six previously undetected, gigantic, stellar structures in the halos of several galaxies that are likely associated with debris from satellites that were tidally disrupted far in the distant past. In addition, we also confirmed several enormous stellar structures previously reported in the literature, but never before interpreted as being tidal streams.” says the team. “Our collection of galaxies presents an assortment of tidal phenomena exhibiting strikingly diverse morphological characteristics. In addition to identifying great circular features that resemble the Sagittarius stream surrounding the Milky Way, our observations have uncovered enormous structures that extend tens of kiloparsecs into the halos of their host’s central spiral. We have also found remote shells, giant clouds of debris within galactic halos, jet-like features emerging from galactic disks and large-scale, diffuse structures that are almost certainly related to the remnants of ancient, already thoroughly disrupted satellites. Together with these remains of possibly long defunct companions, our survey also captured surviving satellites caught in the act of tidal disruption. Some of these display long tails extending away from the progenitor satellite very similar to the predictions forecasted by cosmological simulations.”

Can you imagine how exciting it is to be part of deep blue science? It is one thing to be a good astrophotographer – even to be an exceptional astrophotographer – but to have your images and processing to be of such high quality as to be contributory to true astronomical research would be an incredible honor. Just ask Ken Crawford…

“Several years ago I was asked to become part of this team and have made several contributions to the survey. I am excited to announce that my latest contribution has resulted in a professional letter that has been recently accepted by the Astronomical Journal.” comments Ken. “There are a few things that make this very special. One, is that Carlos Frenk the director of the Institute for Computational Cosmology at Durham University (UK) and his team found that my image of galaxy NGC7600 was similar enough to help validate their computer model (simulation) of how larger galaxies form by absorbing satellite dwarf galaxies and why we do not see large number of dwarf galaxies today.”

Dr. Carlos Frenk has been featured on several television shows on the Science and Discovery channels, to name a few, to explain and show some of these amazing simulations. He is the director of the Institute for Computational Cosmology at Durham University (UK), was one of the winners of the 2011 Cosmology Prize of The Peter and Patricia Gruber Foundation.

“The cold dark matter model has become the leading theoretical picture for the formation of structure in the Universe. This model, together with the theory of cosmic inflation, makes a clear prediction for the initial conditions for structure formation and predicts that structures grow hierarchically through gravitational instability.” says Frenk (et al). “Testing this model requires that the precise measurements delivered by galaxy surveys can be compared to robust and equally precise theoretical calculations.”

The formation of shell galaxies in the cold dark matter universe from Kenneth Crawford on Vimeo.

“The galaxy I want to show you has some special features called ‘shells’. I had to image very deep to detect these structures and carefully process them so you can see the delicate structures within.” explains Crawford. “The galaxy name is NGC7600 and these shell structures have not been captured as well in this galaxy before. The movie above shows my image of NGC7600 blending into the simulation at about the point when the shells start to form. The movie below shows the complete simulation.”

“What is ground breaking is that the simulation uses the cold dark matter theory modeling the dark matter halos of the galaxies and as you can see, it is pretty convincing.” concludes Crawford. “So now you all know why we do not observe lots of dwarf galaxies in the Universe.”

But, we can observe some very incredible science done by some very incredible friends. It’s what matters…

For Further Reading: Tracing Out the Northern Tidal Stream of the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy, Stellar Tidal Streams in Spiral Galaxies of the Local Volume, Carlos Frenk, Simulations of the formation, evolution and clustering of galaxies and quasars, The formation of shell galaxies similar to NGC 7600 in the cold dark matter cosmogony, Star Stream Survey Images By Ken Crawford and be sure to check out the zoomable Full Size Image of NGC 7600 done by Ken Crawford. We thank you all so much for sharing your work with us!