[/caption]

Mars Science Laboratory, launched three days ago on the morning of Saturday, November 26, is currently on its way to the Red Planet – a journey that will take nearly nine months. When it arrives the first week of August 2012, MSL will begin investigating the soil and atmosphere within Gale Crater, searching for the faintest hints of past life. And unlike the previous rovers which ran on solar energy, MSL will be nuclear-powered, generating its energy through the decay of nearly 8 pounds of plutonium-238. This will potentially keep the next-generation rover running for years… but what will fuel future exploration missions now that NASA may no longer be able to fund the production of plutonium?

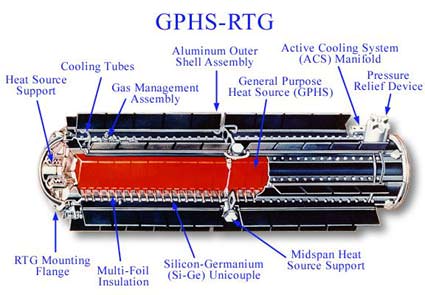

Pu-238 is a non-weapons-grade isotope of the radioactive element, used by NASA for over 50 years to fuel exploration spacecraft. Voyagers, Galileo, Cassini… all had radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) that generated power via Pu-238. But the substance has not been in production in the US since the late 1980s; all Pu-238 has since been produced in Russia. But now there’s only enough left for one or two more missions and the 2012 budget plan does not yet allot funding for the Department of Energy to continue production.

Where will future fuel come from? How will NASA power its next lineup of robotic explorers? (And why aren’t more people concerned about this?)

Amateur astronomer, teacher and blogger David Dickinson went into detail about this conundrum in an informative article written earlier this year. Here are some excerpts from his post:

________________

When leaving our fair planet, mass is everything. Space being a harsh place, you must bring nearly everything you need, including fuel, with you. And yes, more fuel means more mass, means more fuel, means… well, you get the idea. One way around this is to use available solar energy for power generation, but this only works well in the inner solar system. Take a look at the solar panels on the Juno spacecraft bound for Jupiter next month… those things have to be huge in order to take advantage of the relatively feeble solar wattage available to it… this is all because of our friend the inverse square law which governs all things electromagnetic, light included.

To operate in the environs of deep space, you need a dependable power source. To compound problems, any prospective surface operations on the Moon or Mars must be able to utilize energy for long periods of sun-less operation; a lunar outpost would face nights that are about two Earth weeks long, for example. To this end, NASA has historically used Radioisotope Thermal Generators (RTGs) as an electric “power plant” for long term space missions. These provide a lightweight, long-term source of fuel, generating from 20-300 watts of electricity. Most are about the size of a small person, and the first prototypes flew on the Transit-4A & 5BN1/2 spacecraft in the early 60’s. The Pioneer, Voyager, New Horizons, Galileo and Cassini spacecraft all sport Pu238 powered RTGs. The Viking 1 and 2 spacecraft also had RTGs, as did the long term Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) experiments that Apollo astronauts placed on the Moon. An ambitious sample return mission to the planet Pluto was even proposed in 2003 that would have utilized a small nuclear engine.

Video: what is plutonium really like?

David goes on to mention the undeniable dangers of plutonium…

Plutonium is nasty stuff. It is a strong alpha-emitter and a highly toxic metal. If inhaled, it exposes lung tissue to a very high local radiation dose with the attending risk of cancer. If ingested, some forms of plutonium accumulate in our bones where it can damage the body’s blood-forming mechanism and wreck havoc with DNA. NASA had historically pegged a chance of a launch failure of the New Horizons spacecraft at 350-to-1 against, which even then wouldn’t necessarily rupture the RTG and release the contained 11 kilograms of plutonium dioxide into the environment. Sampling conducted around the South Pacific resting place of the aforementioned Apollo 13 LM re-entry of the ascent stage of the Lunar Module, for example, suggests that the reentry of the RTG did NOT rupture the container, as no plutonium contamination has ever been found.

Yet the dangers of nuclear power often overshadow its relative safety and unmistakable benefit:

The black swan events such as Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima have served to demonize all things nuclear, much like the view that 19thcentury citizens had of electricity. Never mind that coal-fired plants put many times the equivalent of radioactive contamination into the atmosphere in the form of lead210, polonium214, thorium and radon gases, every day. Safety detectors at nuclear plants are often triggered during temperature inversions due to nearby coal plant emissions… radiation was part of our environment even before the Cold War and is here to stay. To quote Carl Sagan, “Space travel is one of the best uses of nuclear weapons that I can think of…”

Yet here we are, with a definite end in sight to the supply of nuclear “weapons” needed to power space travel…

Currently, NASA faces a dilemma that will put a severe damper on outer solar system exploration in the coming decade. As mentioned, current plutonium reserves stand at about enough for the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity, which will contain 4.8kilograms of plutonium dioxide, and one last large & and perhaps one small outer solar system mission. MSL utilizes a new generation MMRTG (the “MM” stands for Multi-Mission) designed by Boeing that will produce 125 watts for up to 14 years. But the production of new plutonium would be difficult. Restart of the plutonium supply-line would be a lengthy process, and take perhaps a decade. Other nuclear based alternatives do indeed exist, but not without a penalty either in low thermal activity, volatility, expense in production, or short half life.

The implications of this factor may be grim for both manned and unmanned space travel to the outer solar system. Juxtaposed against at what the recent 2011 Decadal Survey for Planetary Exploration proposes, we’ll be lucky to see many of those ambitious “Battlestar Galactica” –style outer solar system missions come to pass.

Landers, blimps and submersibles on Europa, Titan, and Enceladus will all operate well out of the Sun’s domain and will need said nuclear power plants to get the job done… contrast this with the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe, which landed on Titan after being released from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft in 2004, which operated for scant hours on battery power before succumbing to the -179.5 C° temps that represent a nice balmy day on the Saturnian moon.

So, what’s a space-faring civilization to do? Certainly, the “not going into space” option is not one we want on the table, and warp or Faster-Than-Light drives a la every bad science fiction flick are nowhere in the immediate future. In [my] highly opinionated view, NASA has the following options:

Exploit other RTG sources at penalty. As mentioned previously, other nuclear sources in the form of Plutonium, Thorium, and Curium isotopes do exist and could be conceivably incorporated into RTGs; all, however, have problems. Some have unfavorable half-lives; others release too little energy or hazardous penetrating gamma-rays. Plutonium238 has high energy output throughout an appreciable life span, and its alpha particle emissions can be easily contained.

Design innovative new technologies. Solar cell technology has come a long way in recent years, making perhaps exploration out to the orbit of Jupiter is do-able with enough collection area. The plucky Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers(which did contain Curium isotopes in their spectrometers!) made do well past their respective warranty dates using solar cells, and NASA’s Dawn spacecraft currently orbiting the asteroid Vesta sports an innovative ion-drive technology.

Push to restart plutonium production. Again, it is not that likely or even feasible that this will come to pass in today’s financially strapped post-Cold War environment. Other countries, such as India and China are looking to “go nuclear” to break their dependence on oil, but it would take some time for any trickle-down plutonium to reach the launch pad. Also, power reactors are not good producers of Pu238. The dedicated production of Pu238 requires either high neutron flux reactors or specialized “fast” reactors specifically designed for the production of trans-uranium isotopes…

Based on the realities of nuclear materials production the levels of funding for Pu238 production restart are frighteningly small. NASA must rely on the DOE for the infrastructure and knowledge necessary and solutions to the problem must fit the realities within both agencies.

And that’s the grim reality of a brave new plutonium-free world that faces NASA; perhaps the solution will come as a combination of some or all of the above. The next decade will be fraught with crisis and opportunity… plutonium gives us a kind of Promethean bargain with its use; we can either build weapons and kill ourselves with it, or we can inherit the stars.

Thanks to David Dickinson for the use of his excellent article; be sure to read the full version on his Astro Guyz site here (and follow David on Twitter @astroguyz.) Also check out this article by Emily Lakdawalla of The Planetary Society on how the RTG unit for Curiosity was made.

“There are some people who legitimately feel like this is simply not a priority, that there’s not enough money and it’s not their problem. But I think if you try to step back and look at the forest and not just the individual trees, this is one of the things that has helped drive us to become a technological powerhouse. What we’ve done with robotic space exploration is something that people not just in the U.S., but around the world, can look up to.”

– Ralph McNutt, planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL)

( Top image credit © 2011 Theodore Gray periodictable.com; used with permission.)