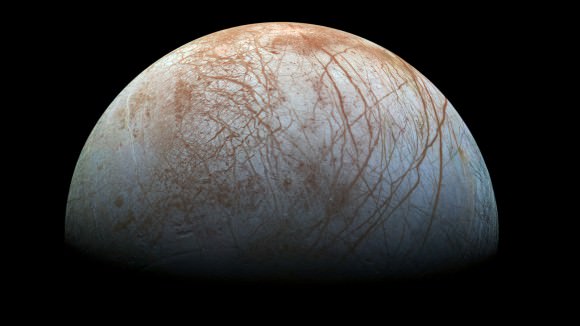

For all of the talk about aliens that we see in science fiction, the reality is in our Solar System, any extraterrestrial life is likely to be microbial. The lucky thing for us is there are an abundance of places that we can search for them — not least Europa, an icy moon of Jupiter believed to harbor a global ocean and that NASA wants to visit fairly soon. What lurks in those waters?

To gain a better understanding of the extremes of life, scientists regularly look at bacteria and other lifeforms here on Earth that can make their living in hazardous spots. One recent line of research involves shrimp that live in almost the same area as bacteria that survive in vents of up to 750 degrees Fahrenheit (400 degrees Celsius) — way beyond the boiling point, but still hospitable to life.

Far from sunlight, the bacteria receive their energy from chemical combinations (specifically, hydrogen sulfide). While the shrimp certainly don’t live in these hostile areas, they perch just at the edge — about an inch away. The shrimp feed on the bacteria, which in turn feed on the hydrogen sulfide (which is toxic to larger organisms if there is enough of it.) Oh, and by the way, some of the shrimps are likely cannibals!

One species called Rimicaris hybisae, according to the evidence, likely feeds on each other. This happens in areas where the bacteria are not as abundant and the organisms need to find some food to survive. To be sure, nobody saw the shrimps munching on each other, but scientists did find small crustaceans inside them — and there are few other types of crustaceans in the area.

But how likely, really, are these organisms on Europa? Bacteria might be plausible, but something larger and more complicated? The researchers say this all depends on how much energy the ecosystems have to offer. And in order to see up close, we’d have to get underwater somehow and do some exploring.

In a recent Universe Today interview with Mike Brown, a professor of planetary science at the California Institute of Technology, the renowned dwarf-planet hunter talked about how a submarine could do some neat work.

“In the proposed missions that I’ve heard, and in the only one that seems semi-viable, you land on the surface with basically a big nuclear pile, and you melt your way down through the ice and eventually you get down into the water,” he said. “Then you set your robotic submarine free and it goes around and swims with the big Europa whales.” You can see the rest of that interview here.

Source: Jet Propulsion Laboratory