Though ISON may have fizzled in early 2014, we’ve certainly had a bevy of binocular comets to track this year. Thus far in 2014, we’ve had comets R1 Lovejoy, K1 PanSTARRS, and E2 Jacques reach binocular visibility. Now, and asteroid-turned-comet is set to put on a fine show this summer for northern hemisphere observers.

Veteran stargazer and Universe Today contributor Bob King told the tale last month of how the asteroid formerly known as 2013 UQ4 became comet 2013 UQ4 Catalina. Discovered last year on October 23rd 2013 during the routine Catalina Sky Survey searching for Near Earth Objects based outside of Tucson Arizona, this object was of little interest until early this year.

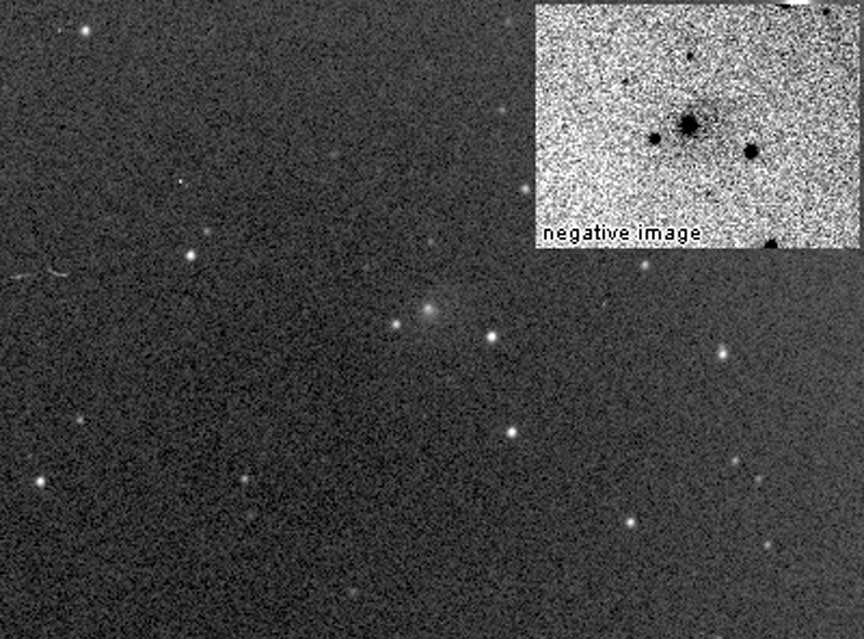

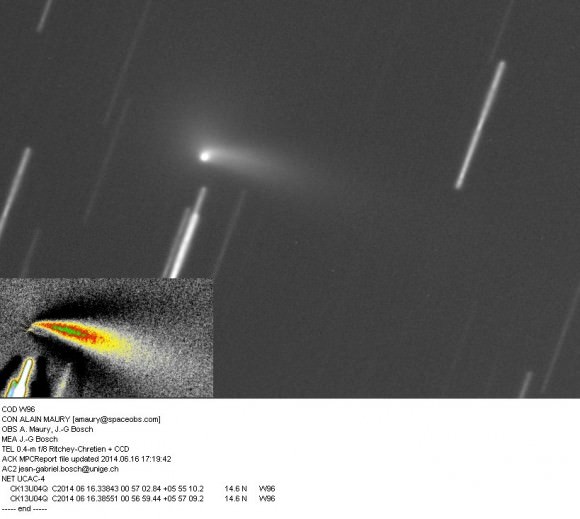

As it rounded the Sun, astronomers recovered the asteroid and discovered that it had begun to sprout a fuzzy coma, a very un-asteroid-like thing to do. Then, on May 7th, Taras Prystavski and Artyom Novichonok — of Comet ISON fame — conducted observations of 2013 UQ4 and concluded that it was indeed an active comet.

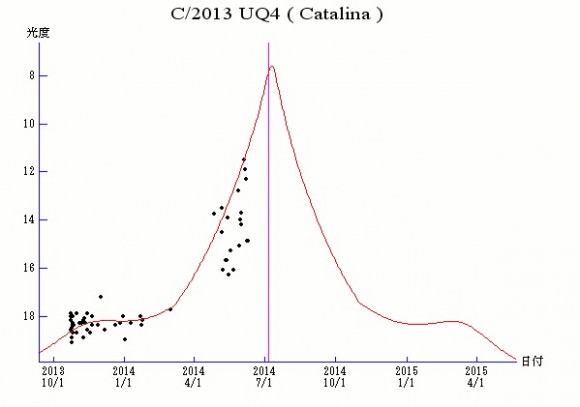

Hovering around +13th magnitude last month, newly rechristened 2013 UQ4 Catalina was a southern hemisphere object visible only from larger backyard telescopes. That should change, however, in the coming weeks if activity from this comet holds up.

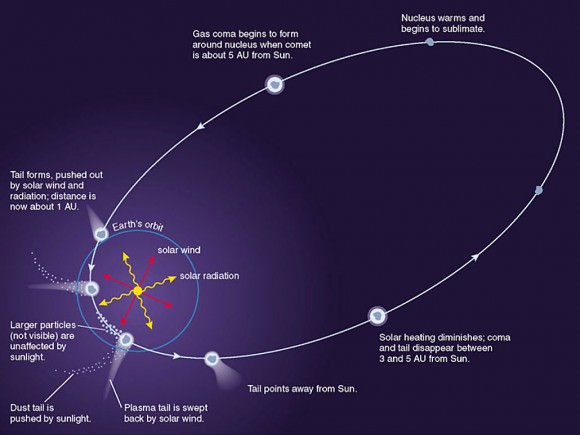

2013 UQ4 belongs to a class of objects known as damocloids. These asteroids are named after the prototype for the class 5335 Damocles and are characterized as long-period bodies in retrograde and highly eccentric orbits. These are thought to be inactive varieties of comet nuclei, and other asteroids in the damocloid series such as C/2001 OG 108 (LONEOS) and C/2002 VQ94 (LINEAR) also turned out to be comets. Damocloids also exhibit the same orbital characteristics of that most famous inner solar system visitor of them all; Halley’s Comet.

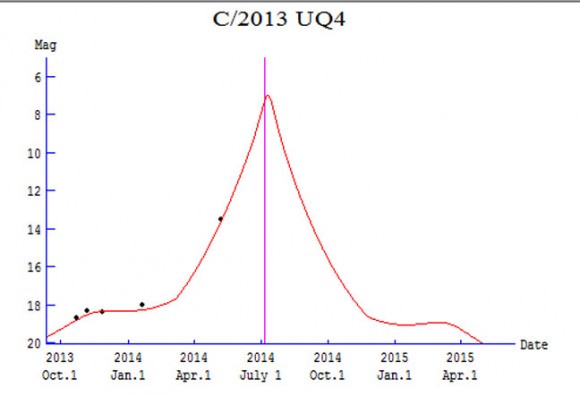

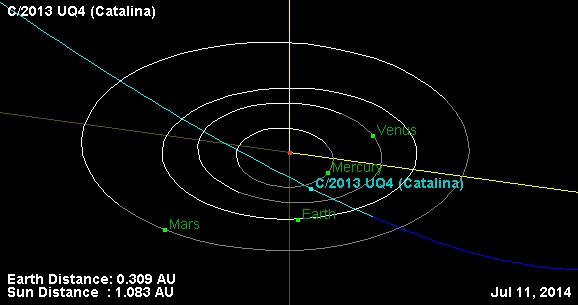

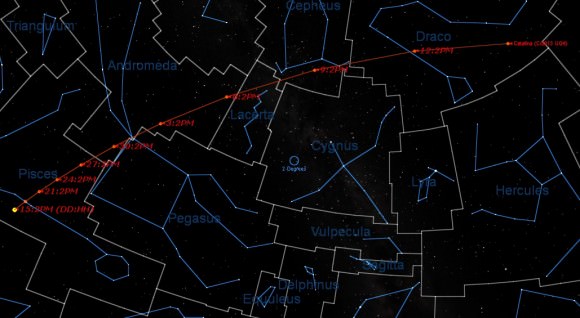

The good news is, 2013 UQ4 Catalina is brightening on schedule and should be a binocular object greater than +10th magnitude by the end of June. Recent observations, including those made by Alan Hale (of comet Hale-Bopp fame) place the comet at magnitude +11.9 with a bullet. The comet is currently placed high in the east in the constellation Pisces at dawn, and will soon speed northward and vault across the sky as it crosses the ecliptic plane this week. In fact, comet 2013 UQ4 Catalina reaches perihelion on July 6th only four days before its closest approach to the Earth at 47 million kilometres distant, when it may well reach a peak magnitude of +7. At that point, the comet will have an apparent motion of about 7 degrees a day — that’s the span of a Full Moon once every 1 hour and 42 minutes — as it rises in the constellation Cepheus to the northeast at dusk in early July. A fine placement, indeed. And speaking of the Moon, our natural satellite reaches New phase later this month on June 27th, another good reason to begin searching for 2013 UQ4 Catalina now.

Here’s a list of notable events to watch out for and aid you in your quest as comet 2013 UQ4 Catalina crosses the summer sky:

June 16th: The comet crosses north of the ecliptic plane.

June 20th: The waning crescent Moon passes 3 degrees from the comet.

June 29th: Crosses into the constellation of Andromeda.

July 1st: Passes less than one degree from the +2nd magnitude star Alpheratz.

July 2nd: Crosses briefly into the constellation Pegasus before passing back into Andromeda.

July 6th: The comet reaches perihelion or its closest point to the Sun at 1.081 A.U.s distant.

July 7th: Crosses into the constellation of Lacerta and passes the deep sky objects NGCs 7296, 7245, 7226.

July 8th: Crosses into the constellation Cepheus and across the galactic plane.

July 9th: Passes a degree from the Elephant Trunk open star cluster.

July 10th: Passes less than one degree from the stars Eta (magnitude +3.4) and Theta (magnitude +4.2) Cephei.

July 10th: Passes 2 degrees from the +7.8 magnitude Open Cluster NGC 6939.

July 10th: Passes closest to Earth at 0.309 A.U.s or 47 million kilometres distant.

July 11th: Crosses into the constellation Draco.

July 11th: Reaches its most northerly declination of 64 degrees.

July 12th: Photo op: the comet passes 3 degrees from the Cat’s Eye Nebula.

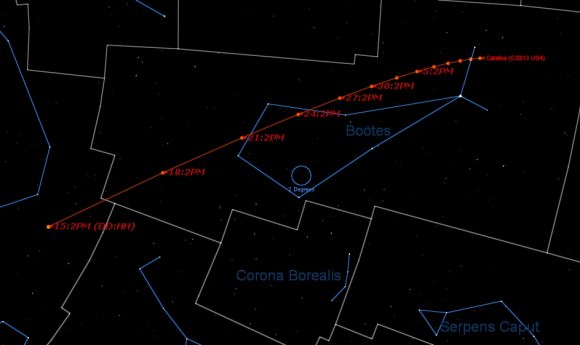

July 17th: The comet passes into the astronomical constellation of Boötes.

July 31st: Passes just 2 degrees from globular cluster NGC5466 (+9th magnitude) and 6 degrees from the famous globular cluster Messier 3.

From there on out, the comet drops below naked eye visibility and heads back out in its 470 year orbit around the Sun. Be sure to check out comet 2013 UQ4 Catalina this summer… what will the Earth be like next time it passes by in 2484 A.D.?