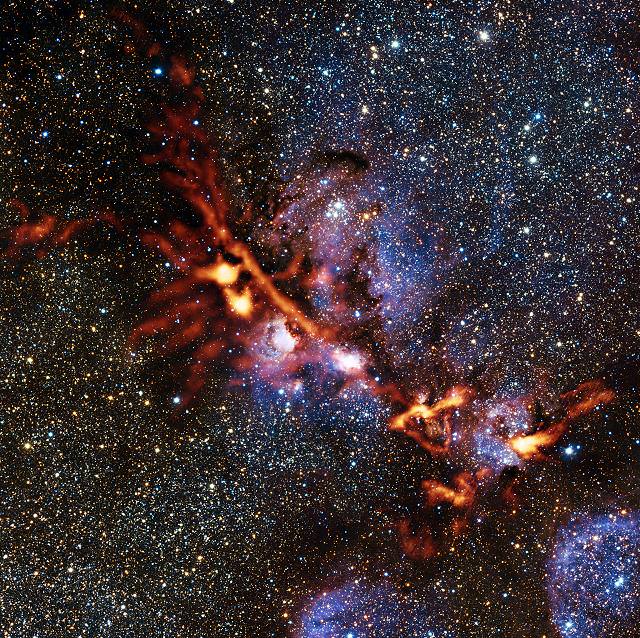

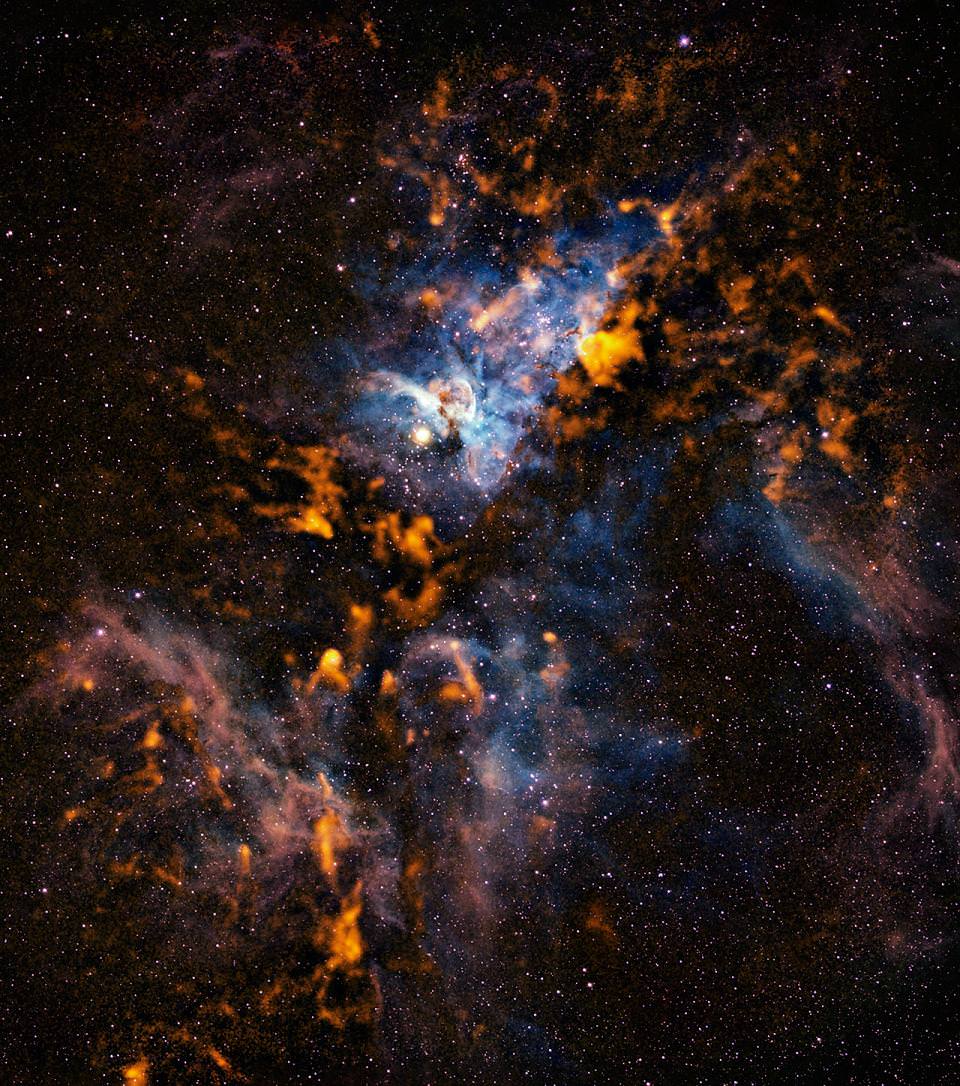

And the “Cat’s Paw” was waiting to strike! In this exceptionally detailed image of star-forming region NGC 6334 we can get a sense of just how important new instrumentation can be. In this case it’s a new camera called ArTeMiS and it has just been installed on a 12-meter diameter telescope located high in the Atacama Desert. The Atacama Pathfinder Experiment – or APEX for short – operates at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths, providing us with observations ranging between radio wavelengths and infrared light. These images give astronomers powerful new data to help them further understand the construction of the Universe.

Exactly what is ArTeMiS? The camera provides wide field views at submillimeter wavelengths. When added to APEX’s arsenal, it will substantially increase the amount of details a particular object has to offer. It has a detector array similar to a CCD camera – a new technology which will enable it to create wide-field maps of target areas with a greater amount of speed and a larger amount of pixels.

Like almost all new telescope projects, both personal and professional, the APEX team met up with “first light” problems. Although the ArTeMiS Camera was ready to go, the weather simply wouldn’t cooperate. According to the news release, very heavy snow on the Chajnantor Plateau had almost buried the building in which the scope operations are housed! However, the team was determined. Using a makeshift road and dodging snow drifts, the team and the staff at the ALMA Operations Support Facility and APEX somehow managed to get the camera to its location safely. Undaunted, they installed the ArTeMiS camera, worked the cryostat into position and locked the instrumentation down in its final position.

However, digging their way out of the snow wasn’t all the team had to contend with. To get ArTeMis on-line, they then had to wait for very dry weather since submillimeter wavelengths of light are highly absorbed by atmospheric moisture. Do good things come to those who wait? You bet. When the “magic moment” arrived, the APEX team was ready and the initial test observations were a resounding success. ArTeMiS quickly became the focus tool for a variety of scientific projects and commissioned observations. One of these projects was to image star-forming region NGC 6334 – the Cat’s Paw Nebula – in the southern constellation of Scorpius. Thanks to the new technology, the ArTeMiS image shows a superior amount of detail over earlier photographic observations taken with APEX.

What’s next for ArTeMiS? Now that the camera has been tested, it will be returned to Saclay in France to have even more detectors installed. According to the researchers: ” The whole team is already very excited by the results from these initial observations, which are a wonderful reward for many years of hard work and could not have been achieved without the help and support of the APEX staff.”

Original Story Source: ESO Public News Release.