Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! If you only get your telescope or binoculars out once in a Blue Moon, then get them out this week when a Blue Moon actually happens! However, if you can’t wait, then let’s explore some great lunar features, bright star clusters and great double stars. When you’re ready to learn some history, mystery and more, then just step on inside…

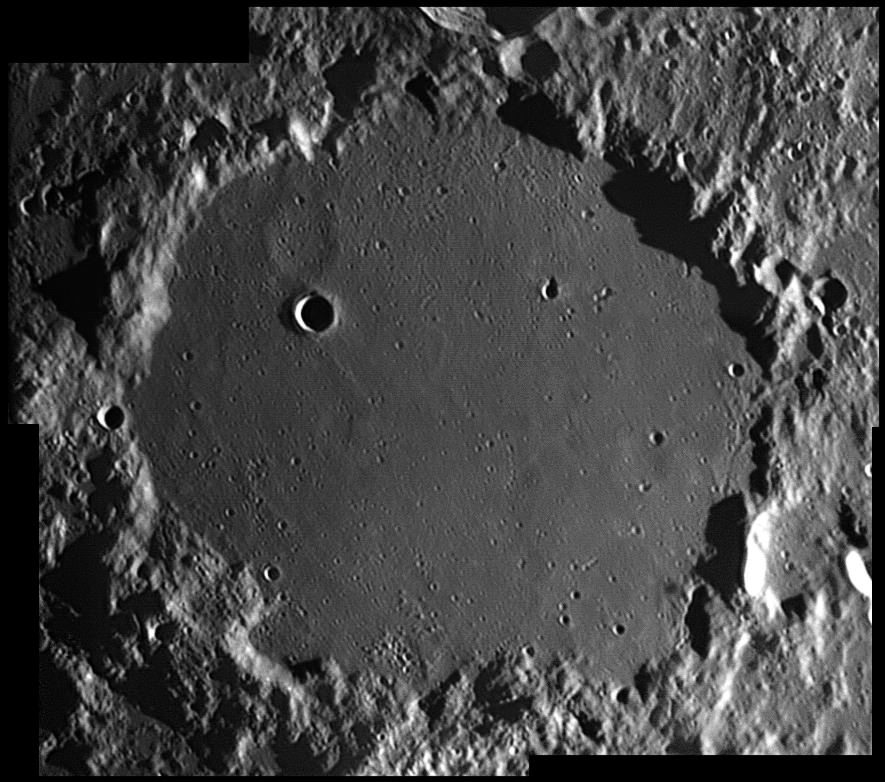

Monday, August 27 – Tonight the waxing Moon’s most notable features will be the vast area of craters dominating the south-central portion near and along the terminator. Now emerging is Ptolemaeus – just north-northeast of Albategnius. This large round crater is a mountain walled plain filled with lava flow. With the exception of interior crater Ptolemaeus A, binoculars will see it as very smooth. Telescopes, however, can reveal faint mottling in the surface of the crater’s interior, along with a single elongated craterlet to the northeast. Despite its apparent uniformity, close inspection has revealed as many as 195 interior craterlets within Ptolemaeus! Look for a variety of interior ridges and shallow depressions.

With the Moon low to the southwest, we have a chance to go northeast to Cepheus for a new study – NGC 7160 (Right Ascension: 21 : 53.7 (hours : minutes) Declination: +62 : 36). At magnitude 6.1, this small open cluster is easily identified in scopes and may be seen as a faint starfield in binoculars. You’ll find it about a finger-width north of Nu Cephei.

Tuesday, August 28 – In 1789 on this day, Sir William Herschel discovered Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

On the lunar surface tonight, we’ll start by following the southward descent of large crater rings Ptolemaeus, Alphonsus, and Arzachel to a smaller, bright one southwest named Thebit. We’re going to have a look at Hell…

Just west of Thebit and its prominent A crater to the northwest, you see the Straight Wall – Rupes Recta – appearing as a thin, white line. Continue south until you see large, eroded crater Deslandres. On its western shore, is a bright ring that marks the boundary of Hell. While this might seem like an unusual name for a crater, it was named for an astronomer – and clergyman!

Once you’ve been to Hell, let’s go to the heavens for NGC 7235 (Right Ascension: 22 : 12.6 – Declination: +57 : 17). Locate the star crowded area of Epsilon Cephei which will also include this 7.7 magnitude open cluster in the same low power field. Give it a try. Look for a small, rectangular assortment of 10th magnitude and fainter stars, including a beautiful ruby red, west-northwest of Epsilon.

Wednesday, August 29 – Due south of mighty Copernicus on the eastern edge of Mare Cognitum, you will see a ruined pair of flattened craters. They are Bonpland and Parry – with Frau Mauro just above them. The smallest and brightest of these ancient twins is the eastern Parry. Have a look at its south wall where a huge section is entirely lost. It was near this location that Ranger 7 ended its successful flight in 1964. Just south of Parry is another example of a well-worn Class V crater. See if you can distinguish the ruins of Guericke. Not much is left save for a slight U-shape to its battered walls. These are some of the oldest visible features on the Moon!

If you’d like to head for something very young, have a look at 6.8 magnitude open cluster NGC 6811 (Right Ascension: 19 : 37.3 – Declination: +46 : 23) in Cygnus. This mid-sized, unusually dense open cluster is found less than finger-width north-northwest of Delta – the westernmost star of the Northern Cross. Like most open clusters, the age of NGC 6811 is measured in millions, rather than billions, of years. Visible in binoculars on most nights, telescopes should show a half dozen or so broadly-spaced resolvable stars overlaying a fainter field. Be sure to return again on a moonless night, and have another look a disparate double Delta!

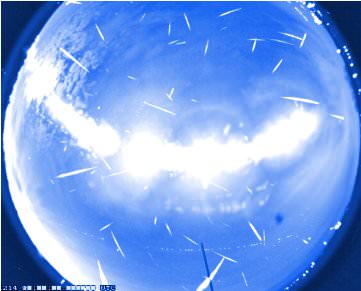

Thursday, August 30 – Today celebrates the Yohkoh Mission, launched in 1991. It was a joint effort of both Japan and the United States to monitor solar flares and the corona. While its initial mission was quite successful, on December 14, 2001 the signal was lost during a total eclipse. Unable to reposition the satellite back towards the Sun, the batteries discharged and Yohkoh became inoperable.

While the graceful Gassendi will try to steal the lunar show tonight, let’s have a go at Foucault instead. To find it, head north to Sinus Iridum and locate Bianchini in the Juras Mountains. Just northeast, and near the shore of south-eastern Mare Frigoris, look for a bright little ring.

Physicist Jean Foucault played an instrumental role in the creation of today’s parabolic mirrors. His “Foucault knife edge test” made it possible for opticians to test mirror curves for optical excellence during the final phases of shaping before metallization. Thanks to Foucault’s insight, we can turn our telescopes on such difficult double stars as Beta Delphini and resolve its 0.6 arc-second distant 5.0 magnitude companion. A challenge for smaller scopes is MU Cygni. This 4.5 and 6.0 magnitude pair should be resolvable in any scope that passed Foucault’s test!

Tonight let’s view a double star, Eta Lyra. Just on the edge of unaided visibility, you will find it around three finger-widths due east of Vega. This wide, disparate pair of 4.5 and 8.0 magnitude stars should be resolvable in just about any scope, but is beyond the reach of binoculars.

Friday, August 31 – Tonight we will begin entering the stream of the Andromedid meteor shower, which peaks off and on for the next couple of months. For those of you in the northern hemisphere, look for the lazy “W” of Cassiopeia to the northeast. This is the radiant – or relative point of origin – for this meteor stream. At times, this shower has been known to be spectacular, but let’s stick with an accepted fall rate of around 20 per hour. These are the offspring of Beila’s Comet, one that split apart leaving radically different streams – much like 73/P Schwassman-Wachmann did last year. These meteors have a reputation for red fireballs with spectacular trains, so watch for them in the weeks ahead.

It’s Blue Moon! That doesn’t mean the Moon is going to be colored any differently – it just means it’s the second full Moon within a month.

Think having all this Moon around is the pits? Then let’s venture to Zeta Sagittarii and have a look at Ascella – “The Armpit of the Centaur.” While you’ll find Zeta easily as the southern star in the handle of the teapot formation, what you won’t find is an easy double. With almost identical magnitudes, Ascella is one of the most difficult of all binaries. Discovered by W. C. Winlock in 1867, the components of this pair orbit each other very quickly – in just a little more than 21 years. While they are about 140 light-years away, this gravitationally bound pair waltz no further apart than our own Sun and Uranus!

Too difficult? Then have a look at Nu Sagittarii – Ain al Rami, or the “Eye of the Archer.” It’s one of the earliest known double stars and was recorded by Ptolemy. While Nu 1 and Nu 2 are actually not physically related to one another, they are an easy split in binoculars. Eastern Nu 2 is a K type spectral giant that is around 270 light-years from our solar system. But take a very close look at the western Nu 1 – while it appears almost as bright, this one is 1850 light-years away! As a bonus, power up in the telescope, because this is one very tight triple star system!

Saturday, September 1 – On this day 1859, solar physicist Richard Carrington (who originally assigned sunspot rotation numbers) observed the first solar flare ever recorded. Naturally enough, an intense aurora followed the next day. 120 years later in 1979, Pioneer 11 made history as it flew by Saturn.

While the Moon essentially appears to be full throughout the night, take the time to compare the western and eastern limbs. To the west, you will see the smooth arc no longer displays high contrast features. To the east you should see a broken edge now in sunset. Watch in the days ahead as many of your favorite craters begin to reveal themselves in a “different light.”

Tonight let’s visit Alya. One of the fainter stars to receive a proper name, Theta Serpens Caput is located around a hand span due east of Beta Ophiuchi. Thankfully, resolving this wide, matched magnitude pair is easier than finding it. If you have high power, self-stabilizing binoculars, this one could be real fun!

Sunday, September 2 – It won’t be long until the Moon lights the skies, so let’s have a look at disparate double Kappa Pegasi. It’s the westernmost star of northern Pegasus and is around a hand span due south of Sadr – the central star of the Northern Cross. At magnitude 4.3, look for a faint companion leading the orange-yellow primary across the sky. This one could be tough for small scopes – so make a challenge of it!

Now let’s have a look at Beta and Gamma Lyrae – the lower two stars in the “Harp.” Beta is actually a quick change variable dropping to less than half the brightness of Gamma every 12 days, but for a few days the two stars appear to be of near equal brightness. Beta is a very unusual eclipsing spectroscopic binary. Its unseen companion may be a “collapsar.”

Before you call it a night, head a finger-width north of Omicron Andromedae for 15 Lacertae. Just on the edge of unaided visibility, this carbon star is also a disparate double. The 5.2 magnitude variable primary will appear more red at its faintest, but its 11.0 magnitude companion is the faintest of all!

But don’t put the telescope away just yet. If you can locate the Moon, you can locate Uranus! Just take a look about 3 degrees away to lunar south to catch the slightly greenish orb of the outer planet.

Until next week, ask for the Moon… But keep on reaching for the stars!

Ptolemaeus Crater Image Credit: Damian Peach