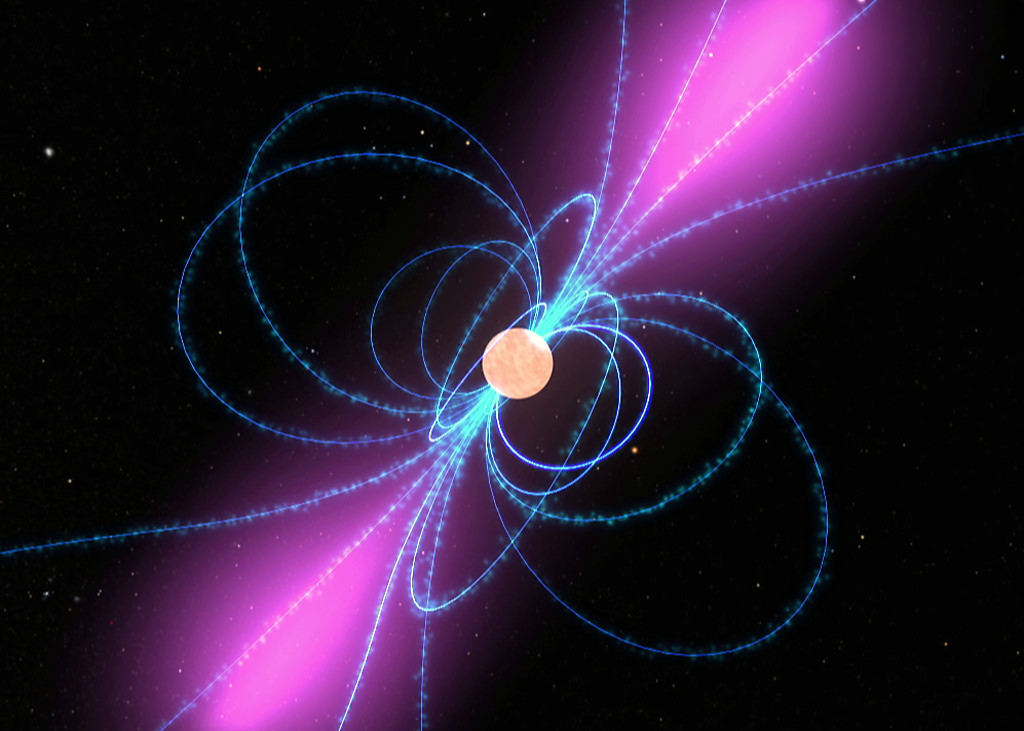

This illustration shows a pulsar’s magnetic field (blue) creates narrow beams of radiation (magenta). Image credit: NASA

How do you detect a ripple in space-time itself? Well, you need hundreds of precision clocks distributed throughout the galaxy, and the Fermi gamma ray telescope has given astronomers a new way to find them.

The “clocks” in question are actually millisecond pulsars – city-sized, sun-massed stars of ultradense matter that spin hundreds of times per second. Due to their powerful magnetic fields, pulsars emit most of their radiation in tightly focused beams, much like a lighthouse. Each spin of the pulsar corresponds to a “pulse” of radiation detectable from Earth. The rate at which millisecond pulsars pulse is extremely stable, so they serve as some of the most reliable clocks in the universe.

Astronomers watch for the slightest variations in the timing of millisecond pulsars which might suggest that space-time near the pulsar is being distorted by the passage of a gravitational wave. The problem is, to make a reliable measurement requires hundreds of pulsars, and until recently they have been extremely difficult to find.

“We’ve probably found far less than one percent of the millisecond pulsars in the Milky Way Galaxy,” said Scott Ransom of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO).

Data from the Fermi gamma-ray space telescope, which started collecting data in 2008, have changed the way millisecond pulsars are detected. The Fermi telescope has identified hundreds of gamma-ray sources in the Milky Way. Gamma rays are high-energy photons, and they are produced near exotic objects, including millisecond pulsars.

“The data from Fermi were like a buried-treasure map,” Ransom said. “Using our radio telescopes to study the objects located by Fermi, we found 17 millisecond pulsars in three months. Large-scale searches had taken 10-15 years to find that many.”

Ransom and collaborator Mallory Roberts of Eureka Scientific used the National Science Foundation’s Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) to find eight of the 17 new pulsars.

Right now astronomers have only barely enough millisecond pulsars to make a convincing gravitational wave detection, but with Fermi to help identify more pulsars, the odds of detecting these ripples in space-time are steadily increasing.

Ransom and Roberts announced their discoveries today at the American Astronomical Society’s meeting in Washington, DC.