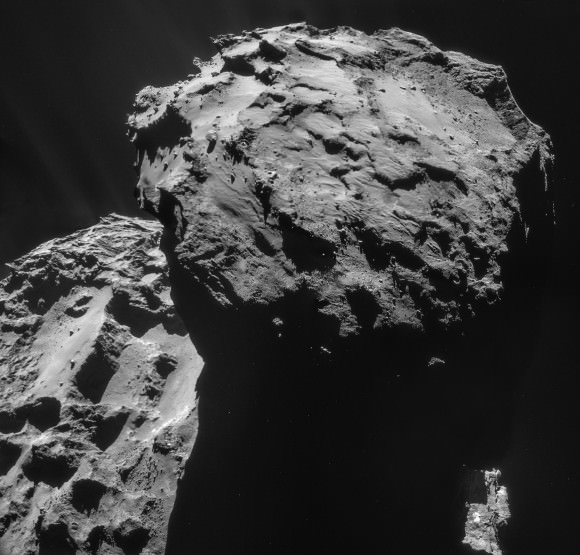

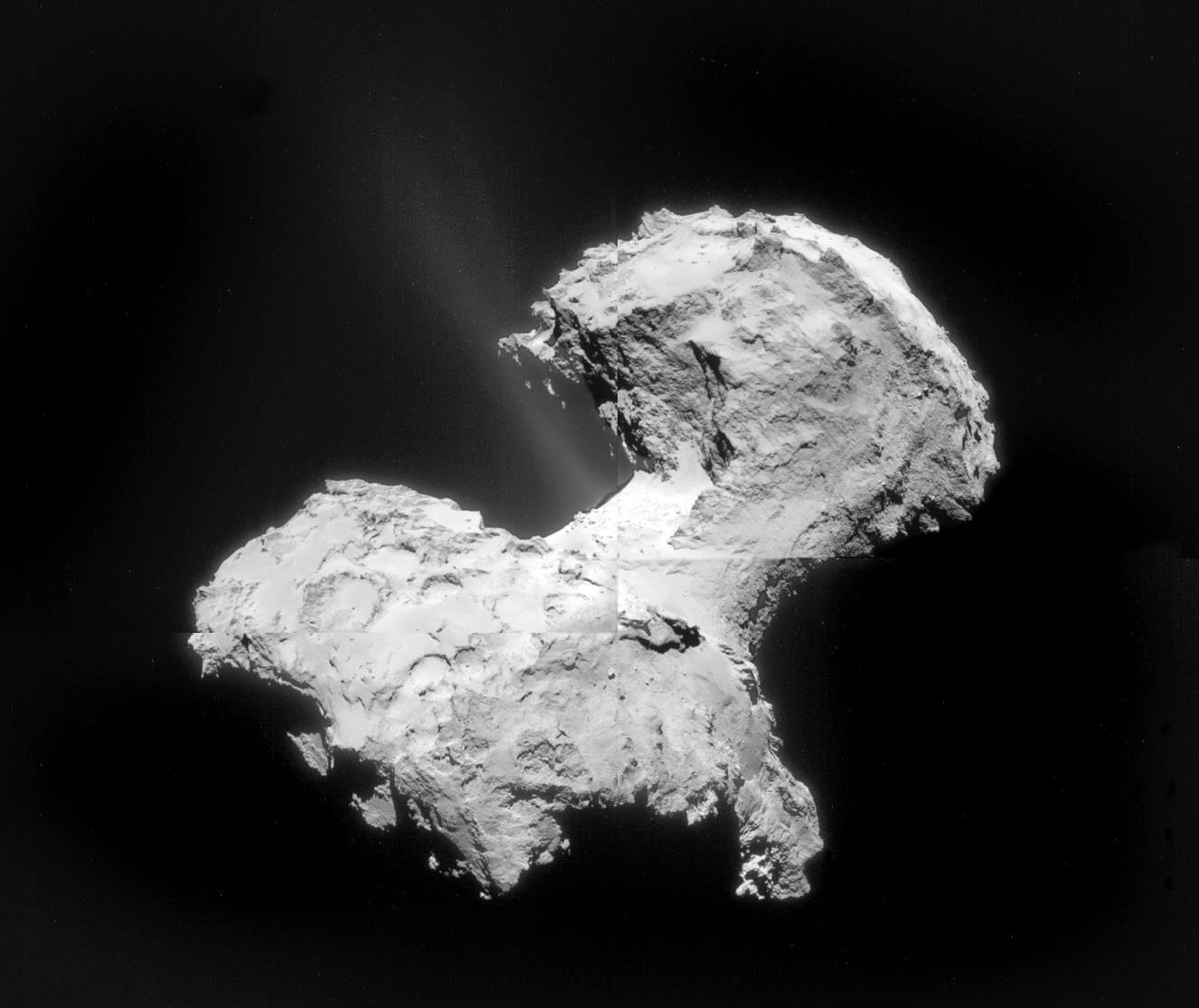

Not all comets break up as they vent and age, but for Rosetta’s comet 67P, the Rubber Duckie comet, a crack in the neck raises concerns. Some comets may just fizzle and uniformly expel their volatiles throughout their surfaces. They may become like puffballs, shrink some but remain intact.

Comet 67P is the other extreme. The expulsion of volatile material has led to a shape and a point of no return; it is destined to break in two. Songwriter Neil Sedaka exclaimed, “Breaking Up is Hard to Do,” but for comets this may be the norm. The fissure is part of the analysis in a new set of science papers published this week.

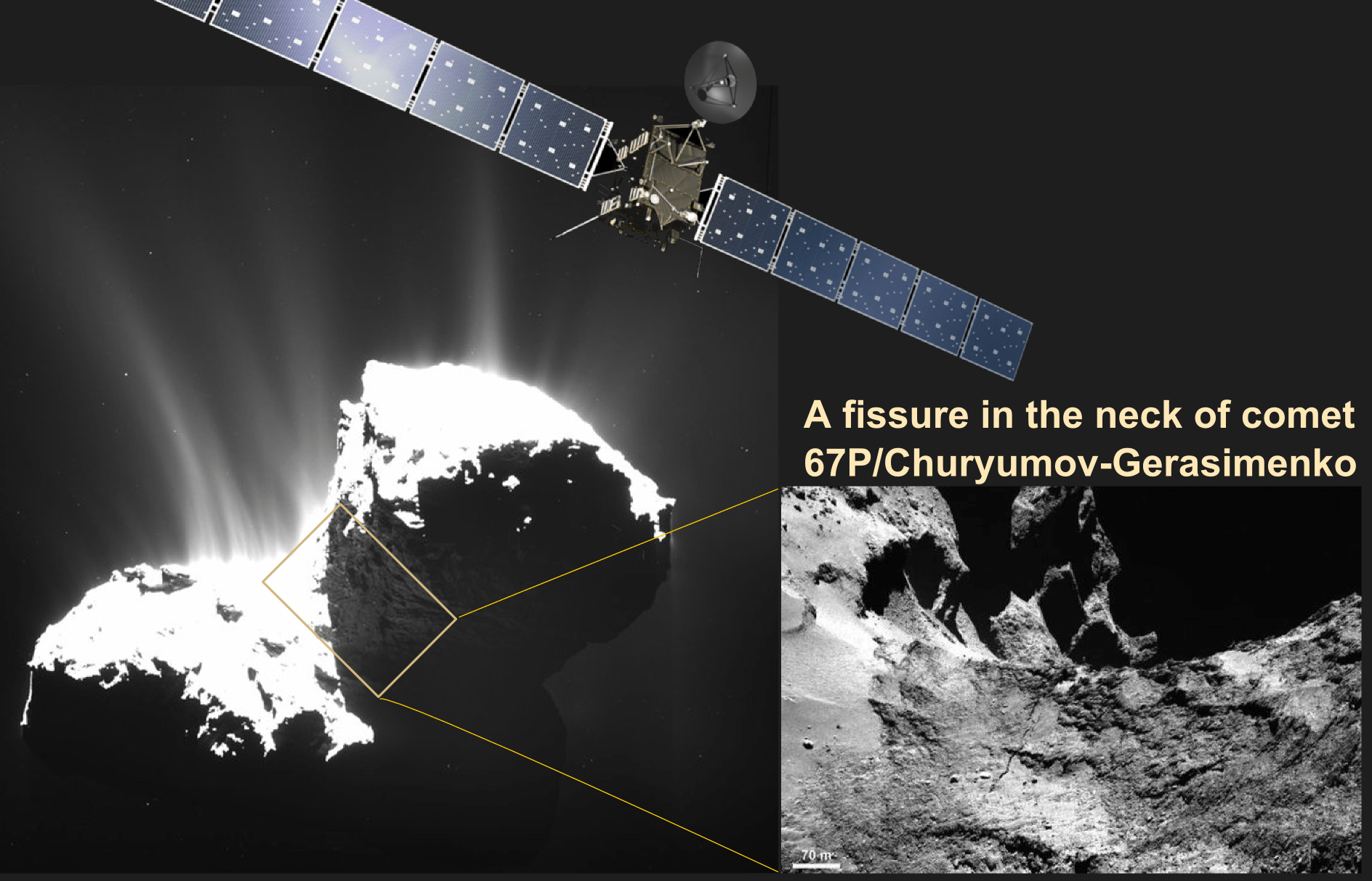

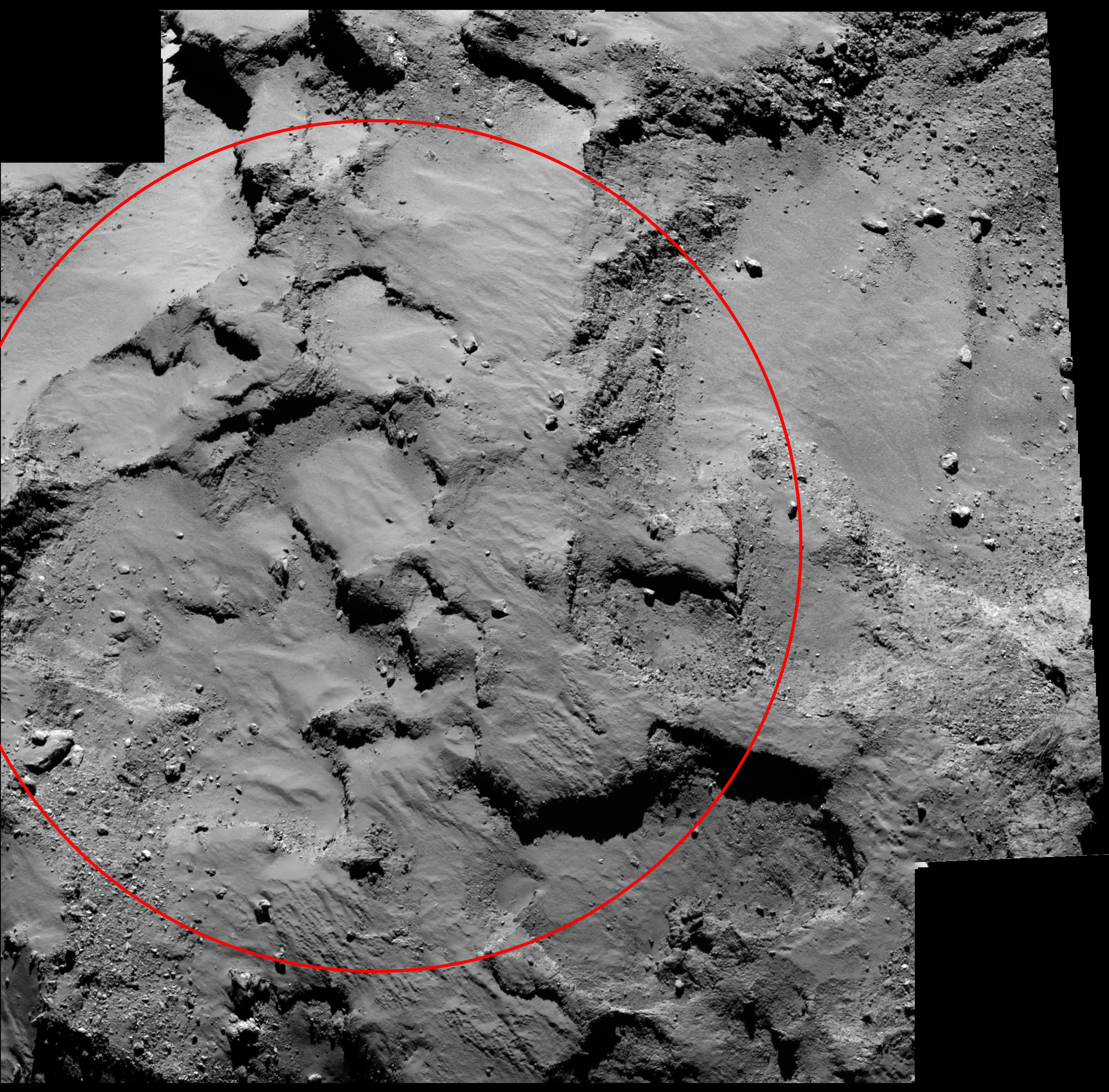

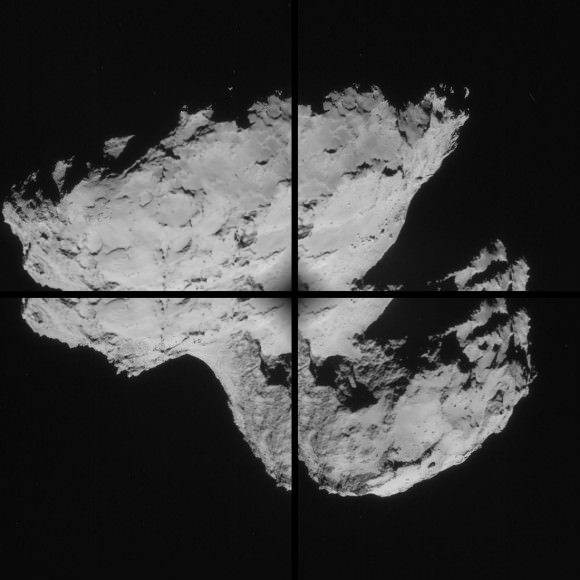

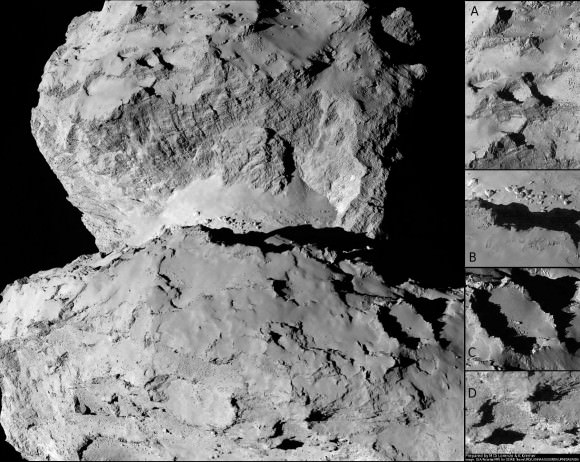

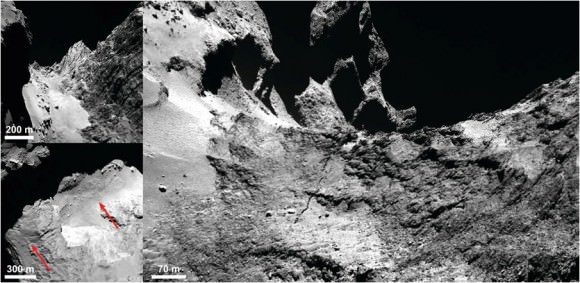

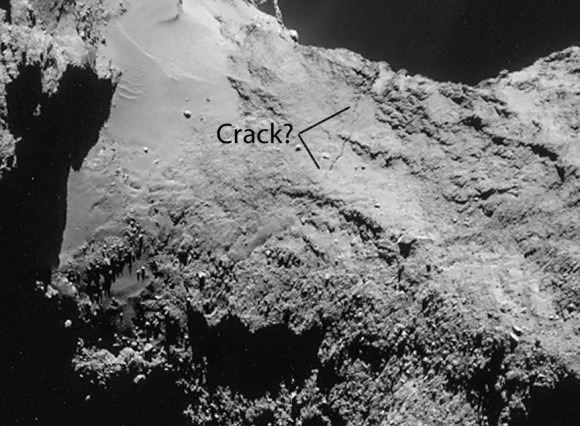

The images show a fissure spanning a few hundred meters across the neck of the two lobe comet.

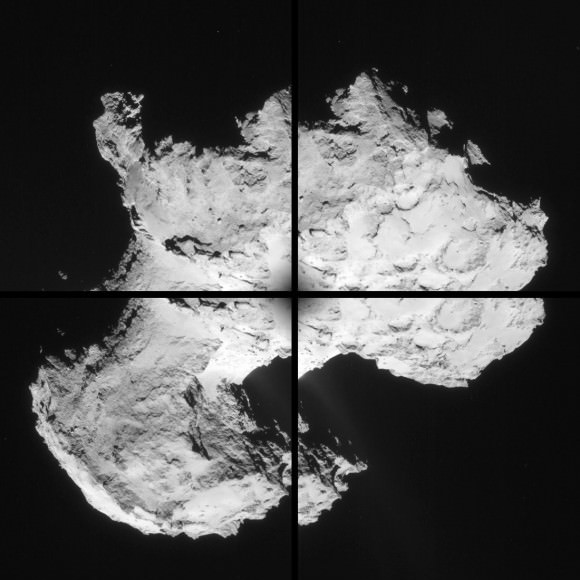

What it means is not certain, but Rosetta team scientists have stated that flexing of the comet might be causing the fissure. As the comet approaches the Sun, the solar radiation is raising the temperature of the surface material. Like all materials, the comet’s will expand and contract with temperature. And diurnal (daily) changes in the tidal forces from the Sun is a factor, too.

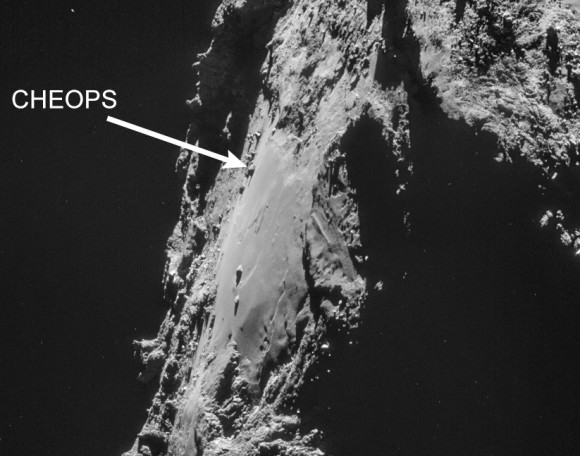

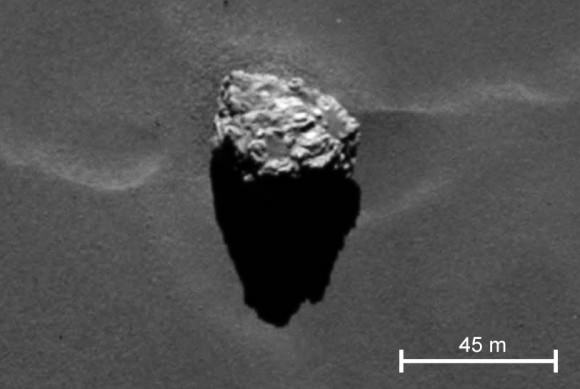

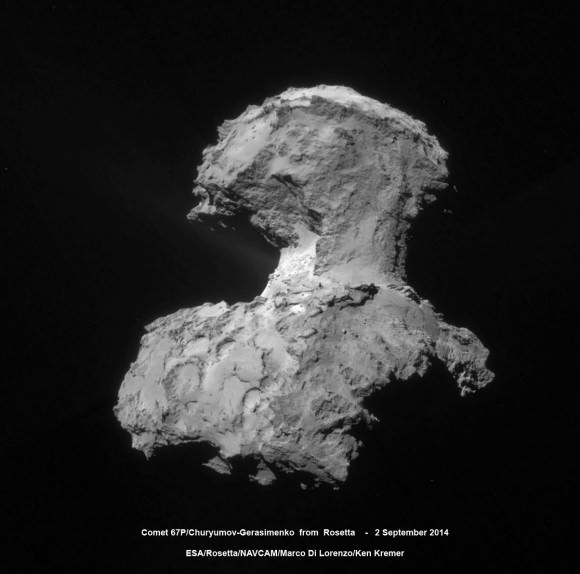

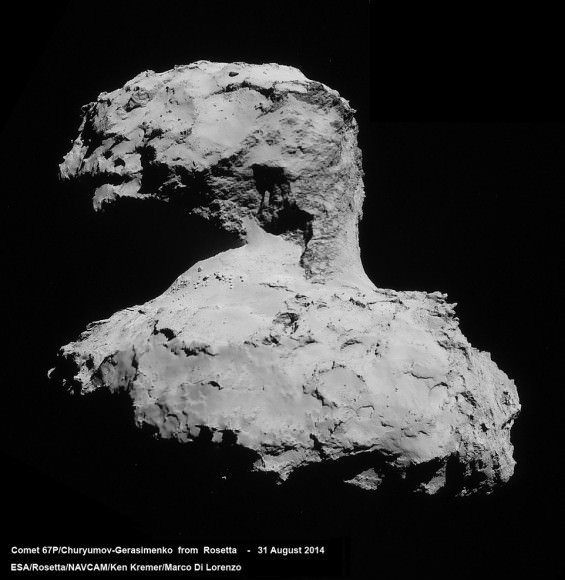

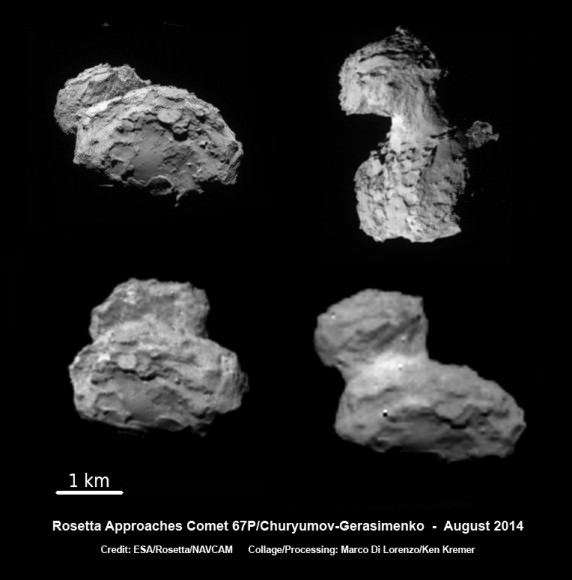

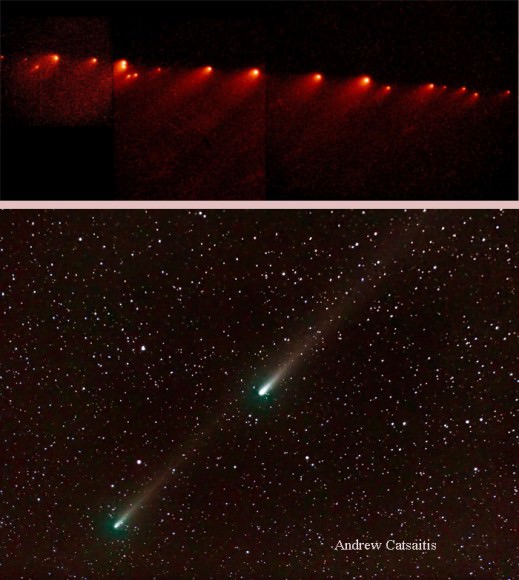

An image sequence from the Navcam of the Rosetta spacecraft (right) is shown beside a simulation. Further work on the interaction of comets with solar radiation will include computer models that utilize Rosetta data to reveal how comet nuclei evolve over time – over many orbits of the Sun- and break up. Peanut, rubber-duck, potatoes or just round-shaped comet nuclei likely result from combinations of rotation, changes in rotation, spin rate, composition and internal structure, as a nucleus interacts with the Sun over many orbits. (Credits: ESA/Rosetta, Illustration – J.Schmidt)

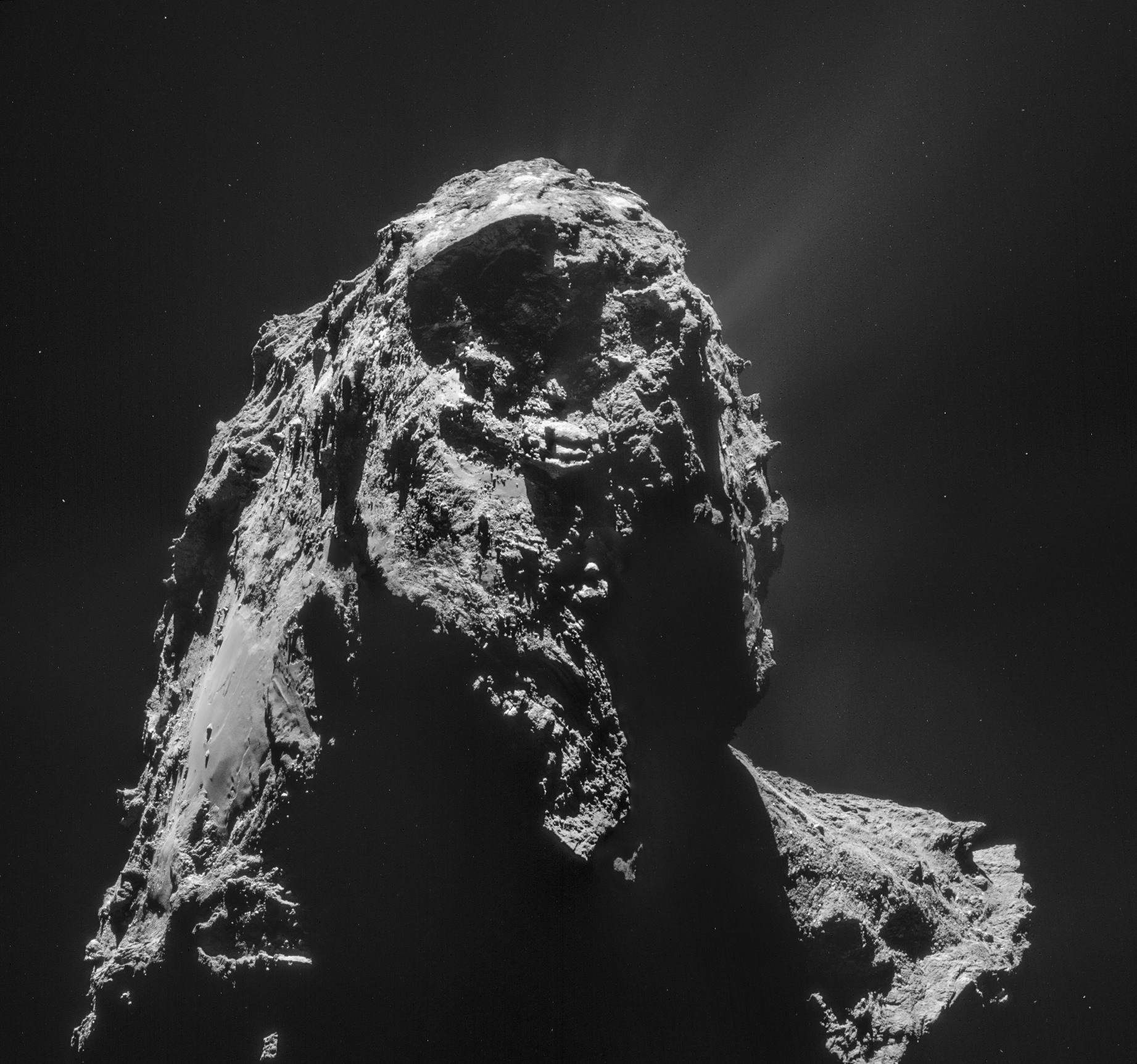

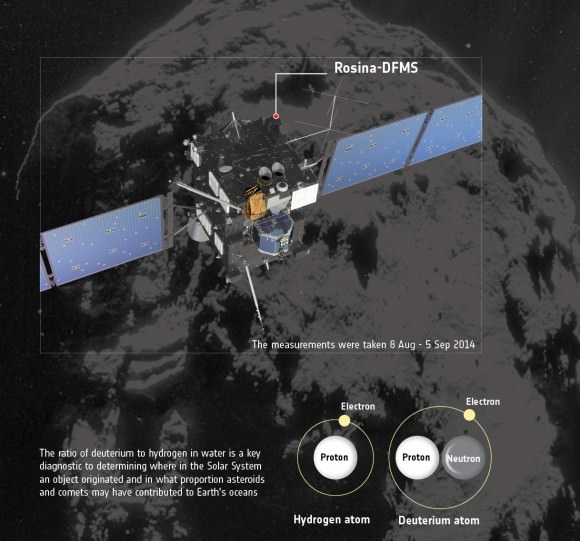

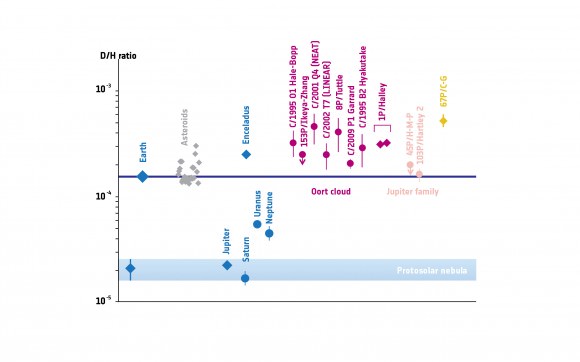

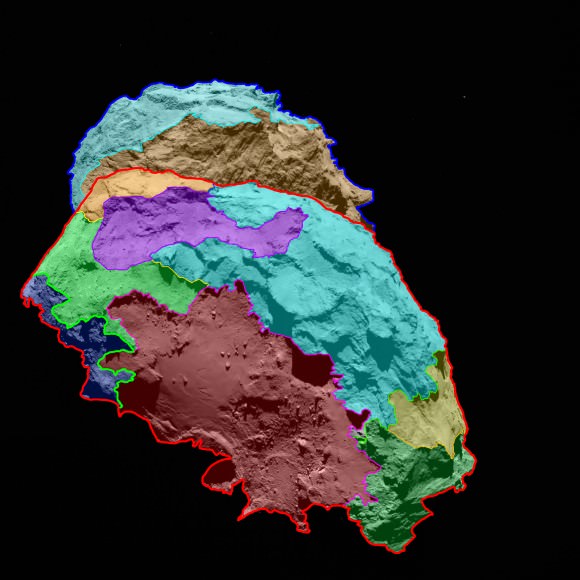

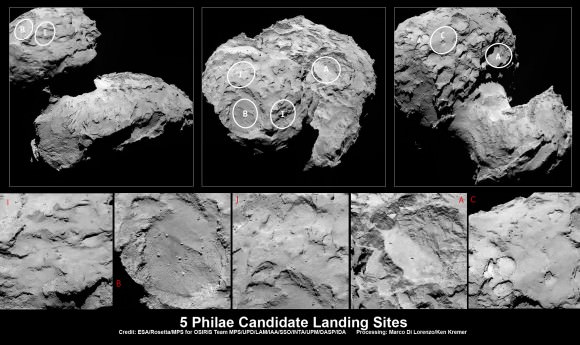

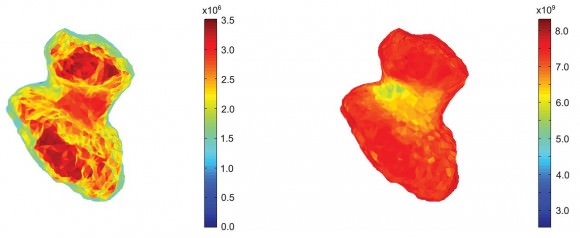

The crack, or fissure, could spell the beginning of the end for comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. It is located in the neck area, in the region named Hapi, between the two lobes that make 67P appear so much like a Rubber Duck from a distance. The fissure could represent a focal point of many properties and forces at work, such as the rotation rate and axis – basically head over heels of the comet. The fissure lies in the most active area at present, and possibly the most active area overall. Though the Hapi region appears to receive nearly constant sunlight, at this time, Rosetta measurements (below) show otherwise – receiving 15% less sunlight than elsewhere.

Sunlight and heating are major factors and the neck likely experiences the greatest mechanical stresses – internal torques – from heating or tidal forces from the sun as it rotates and approaches perihelion. Rosetta scientists are still not certain whether 67P is two bodies in contact – a contact binary – or a shape that formed from material expelled about the neck area leading to its narrowing.

The Philae lander’s MUPUS thermal sensor measured a temperature of –153°C (–243°F) at the landing site, while VIRTIS, an instrument on the primary spacecraft Rosetta, has measured -70°C (-94°F) at present. These temperatures will rise as perihelion is reached on August 13, 2015, at a distance of 1.2432 A.U. (24% further from the Sun than Earth). At present – January 23rd – 67P is 2.486 A.U. from the Sun (2 1/2 times farther from the Sun than Earth). While not a close approach to the Sun for a comet, the Solar radiation intensity will increase by 4 times between the present (January 2014) and perihelion in August.

Stresses due to temperature changes from diurnal variations, the changing Sun angle during perihelion approach, from loss of material, and finally from changes in the tidal forces on a daily basis (12.4043 hours) may lead to changes in the fissure causing it to possibly widen or increase in length. Rosetta will continue escorting the comet and delivering images of the whole surface that will give Rosetta scientists the observations and measurements to determine 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko’s condition now and its fate in the longer term.

Stay tuned for a forthcoming article from UT’s writer Bob King about numerous Rosetta mission scientific findings published this week in the journal Science.

Reference:

The morphological diversity of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

On the nucleus structure and activity of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko