That might seem like a sensational headline worthy of a supermarket tabloid but, taken in context, it’s exactly what’s happening here!

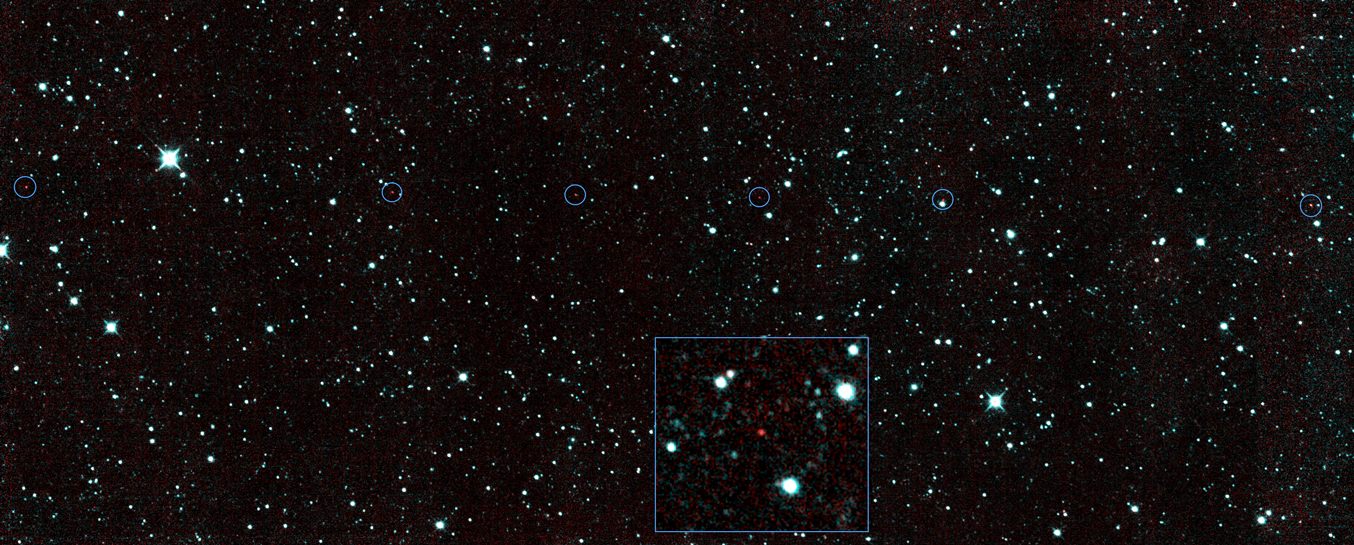

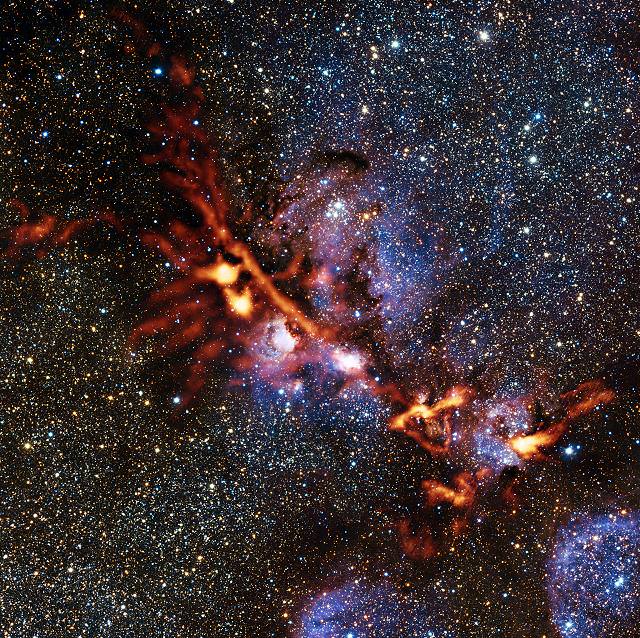

The bright blue star at the center of this image is a B-type supergiant named Kappa Cassiopeiae, 4,000 light-years away. As stars in our galaxy go it’s pretty big — over 57 million kilometers wide, about 41 times the radius of the Sun. But its size isn’t what makes K Cas stand out — it’s the infrared-bright bow shock it’s creating as it speeds past its stellar neighbors at a breakneck 1,100 kilometers per second.

K Cas is what’s called a runway star. It’s traveling very fast in relation to the stars around it, possibly due to the supernova explosion of a previous nearby stellar neighbor or companion, or perhaps kicked into high gear during a close encounter with a massive object like a black hole.

As it speeds through the galaxy it creates a curved bow shock in front of it, like water rising up in front of the bow of a ship. This is the ionized glow of interstellar material compressed and heated by K Cas’ stellar wind. Although it looks like it surrounds the star pretty closely in the image above, the glowing shockwave is actually about 4 light-years out from K Cas… slightly less than the distance from the Sun to Proxima Centauri.

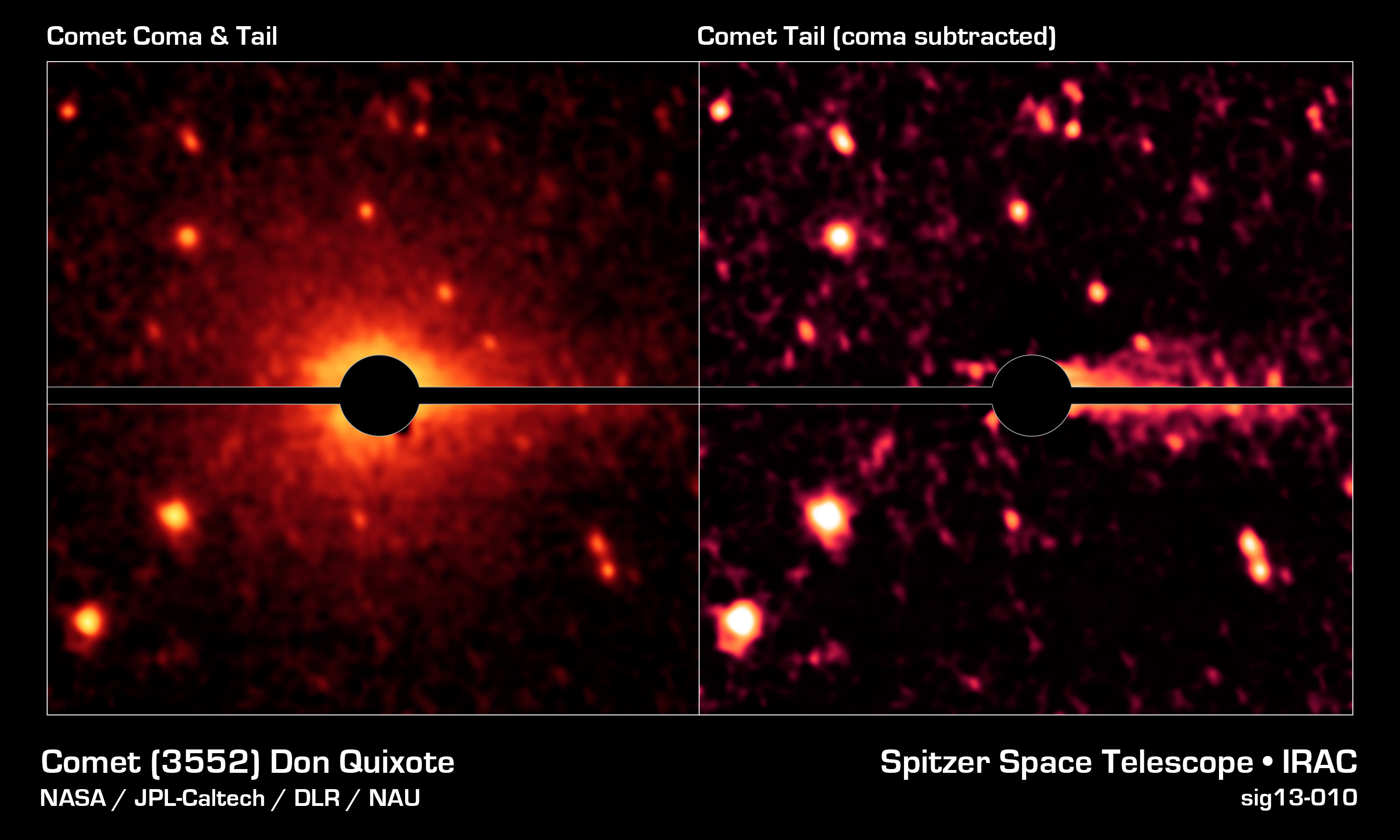

Although K Cas is visible to the naked eye, its bow shock isn’t. It’s only made apparent in infrared wavelengths, which NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope is specifically designed to detect. Some other runaway stars have brighter bow shocks — like Zeta Ophiuchi at right — which can be seen in optical wavelengths (as long as they’re not obscured by dust, which Zeta Oph is.)

Related: Surprise! IBEX Finds No Bow ‘Shock’ Outside our Solar System

The bright wisps seen crossing K Cas’ bow shock may be magnetic filaments that run throughout the galaxy, made visible through interaction with the ionized gas. In fact bow shocks are of particular interest to astronomers precisely because they help reveal otherwise invisible features and allow deeper investigation into the chemical composition of stars and the regions of the galaxy they are traveling through. Like a speeding car on a dark country road, runaway stars’ bow shocks are — to scientists — like high-beam headlamps lighting up the space ahead.

Runaway stars are not to be confused with rogue stars, which, although also feel the need for speed, have been flung completely out of their home galaxies.

Source: NASA