An uncontrolled, chaotic landing. Stuck in the shadow of a cliff without energy-giving sunlight. Philae and team persevered. With just 60 hours of battery power, the lander drilled, hammered and gathered science data on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko before going into hibernation. Here’s what we know.

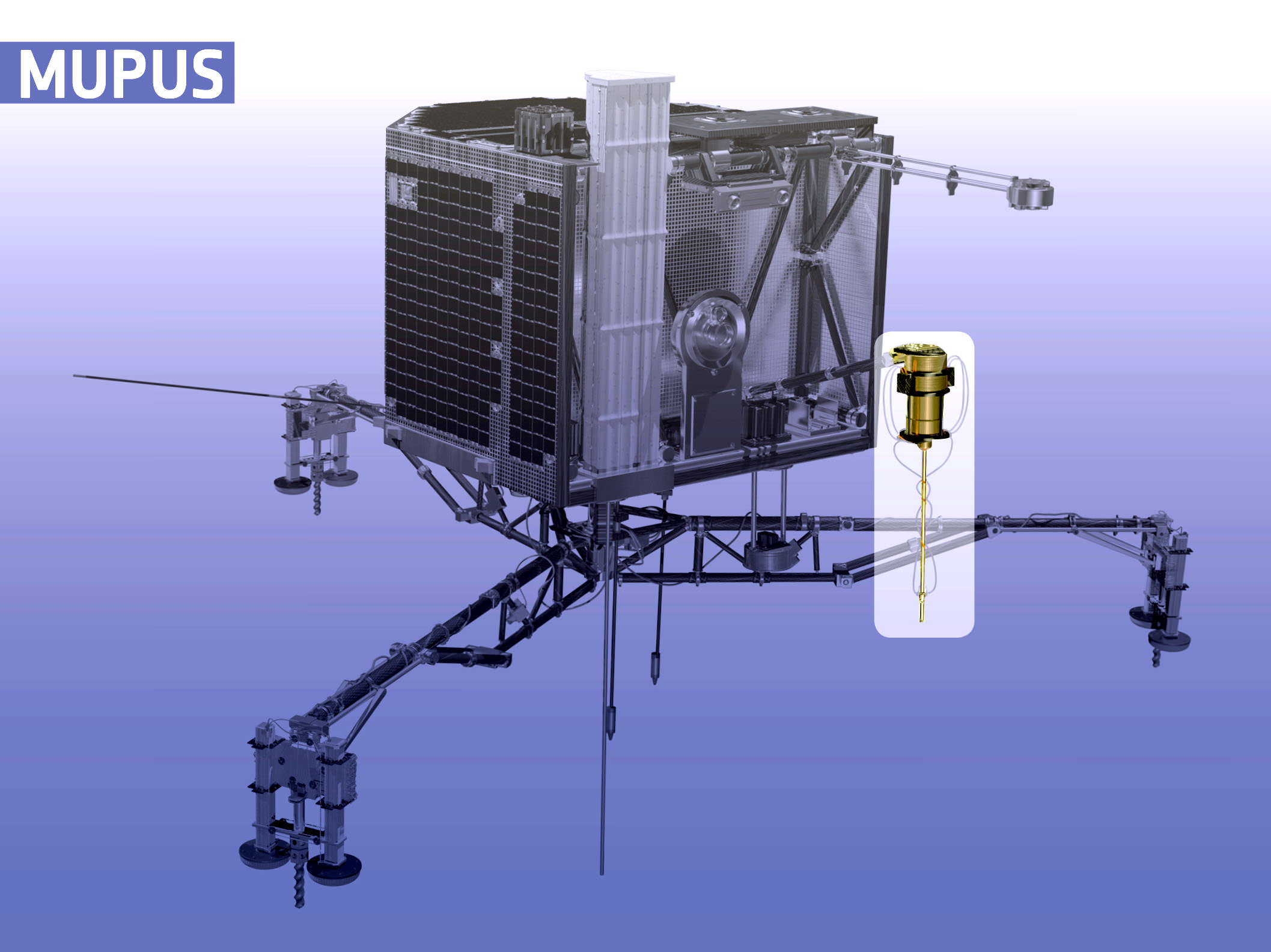

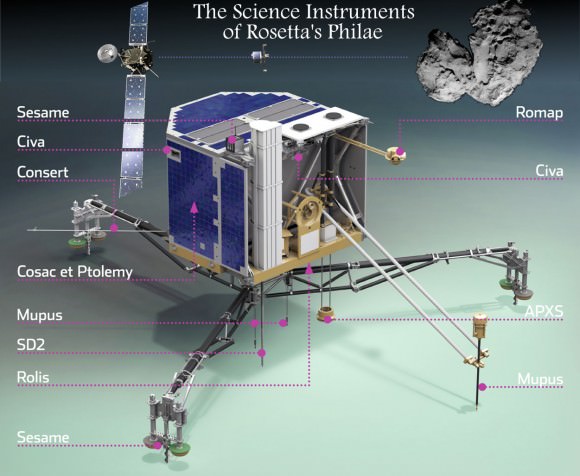

Despite appearances, the comet’s hard as ice. The team responsible for the MUPUS (Multi-Purpose Sensors for Surface and Sub-Surface Science) instrument hammered a probe as hard as they could into 67P’s skin but only dug in a few millimeters:

“Although the power of the hammer was gradually increased, we were not able to go deep into the surface,” said Tilman Spohn from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, who leads the research team. “If we compare the data with laboratory measurements, we think that the probe encountered a hard surface with strength comparable to that of solid ice,” he added. This shouldn’t be surprising, since ice is the main constituent of comets, but much of 67P/C-G appears blanketed in dust, leading some to believe the surface was softer and fluffier than what Philae found.

This finding was confirmed by the SESAME experiment (Surface Electrical, Seismic and Acoustic Monitoring Experiment) where the strength of the dust-covered ice directly under the lander was “surprisingly high” according to Klaus Seidensticker from the DLR Institute. Two other SESAME instruments measured low vaporization activity and a great deal of water ice under the lander.

As far as taking the comet’s temperature, the MUPUS thermal mapper worked during the descent and on all three touchdowns. At the final site, MUPUS recorded a temperature of –243°F (–153°C) near the floor of the lander’s balcony before the instrument was deployed. The sensors cooled by a further 10°C over a period of about a half hour:

“We think this is either due to radiative transfer of heat to the cold nearby wall seen in the CIVA images or because the probe had been pushed into a cold dust pile,” says Jörg Knollenberg, instrument scientist for MUPUS at DLR. After looking at both the temperature and hammer probe data, the Philae team’s preliminary take is that the upper layers of the comet’s surface are covered in dust 4-8 inches (10-20 cm), overlaying firm ice or ice and dust mixtures.

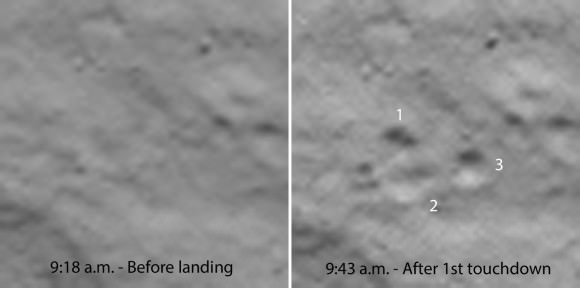

The ROLIS camera (ROsetta Lander Imaging System) took detailed photos during the first descent to the Agilkia landing site. Later, when Philae made its final touchdown, ROLIS snapped images of the surface at close range. These photos, which have yet to be published, were taken from a different point of view than the set of panorama photos already received from the CIVA camera system.

During Philae’s active time, Rosetta used the CONSERT (COmet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Radio wave Transmission) instrument to beam a radio signal to the lander while they were on opposite sides of the comet’s nucleus. Philae then transmitted a second signal through the comet back to Rosetta. This was to be repeated 7,500 times for each orbit of Rosetta to build up a 3D image of 67P/C-G’s interior, an otherworldly “CAT scan” as it were. These measurements were being made even as Philae lapsed into hibernation. Deeper down the ice becomes more porous as revealed by measurements made by the orbiter.

The last of the 10 instruments on board the Philae lander to be activated was the SD2 (Sampling, Drilling and Distribution subsystem), designed to provide soil samples for the COSAC and PTOLEMY instruments. Scientists are certain the drill was activated and that all the steps to move a sample to the appropriate oven for baking were performed, but the data right now show no actual delivery according to a tweet this morning from Eric Hand, reporter at Science Magazine. COSAC worked as planned however and was able to “sniff” the comet’s rarified atmosphere to detect the first organic molecules. Research is underway to determine if the compounds are simple ones like methanol and ammonia or more complex ones like the amino acids.

Stephan Ulamec, Philae Lander manager, is confident that we’ll resume contact with Philae next spring when the Sun’s angle in the comet’s sky will have shifted to better illuminate the lander’s solar panels. The team managed to rotate the lander during the night of November 14-15, so that the largest solar panel is now aligned towards the Sun. One advantage of the shady site is that Philae isn’t as likely to overheat as 67P approaches the Sun en route to perihelion next year. Still, temperatures on the surface have to warm up before the battery can be recharged, and that won’t happen until next summer.

Let’s hang in there. This phoenix may rise from the cold dust again.