Cherenkov radiation is named after the Russian physicist who first worked it out in detail, in 1934, Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov (he got a Nobel for his work, in 1958; because he’s Russian, it’s also sometimes called Cerenkov radiation).

Nothing’s faster than c, the speed of light … in a vacuum. In the air or water (or glass), the speed of light is slower than c. So what happens when something like a cosmic ray proton – which is moving way faster than the speed of light in air or water – hits the Earth’s atmosphere? It emits a cone of light, like the sonic boom of a supersonic plane; that light is Cherenkov radiation.

The Cherenkov radiation spectrum is continuous, and its intensity increases with frequency (up to a cutoff); that’s what gives it the eerie blue color you see in pictures of ‘swimming pool’ reactors.

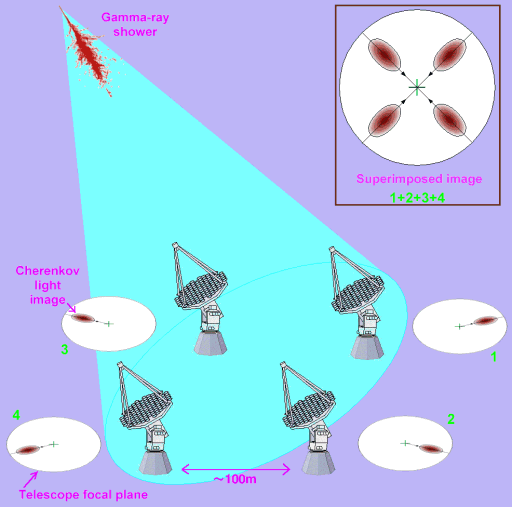

Perhaps the best known astronomical use of Cherenkov radiation is in ICATs such CANGAROO (you guessed it, it’s in Australia!), H.E.S.S. (astronomers love this sort of thing, that’s a ‘tribute’ to Victor Hess, pioneer of cosmic rays studies), and VERITAS (see if you can explain the pun in that!). As a high energy gamma ray, above a few GeV, enters the atmosphere, it creates electron-positron pairs, which initiate an air shower. The shower creates a burst of Cherenkov radiation lasting a few nanoseconds, which the ICAT detects. Because Cherenkov radiation is well-understood, the bursts caused by gamma rays can be distinguished from those caused by protons; and by using several telescopes, the source ‘on the sky’ can be pinned down much better (that’s what one of the Ss in H.E.S.S. stands for, stereoscopic).

The more energetic a cosmic ray particle, the bigger the air shower it creates … so to study really energetic cosmic rays – those with energies above 10^18 ev (which is 100 million times as energetic as what the LHC will produce), which are called UHECRs (see if you can guess) – you need cosmic ray detectors spread over a huge area. That’s just what the Pierre Auger Cosmic Ray Observatory is; and its workhorse detectors are tanks of water with photomultiplier tubes in the dark (to detect the Cherenkov radiation of air shower particles).

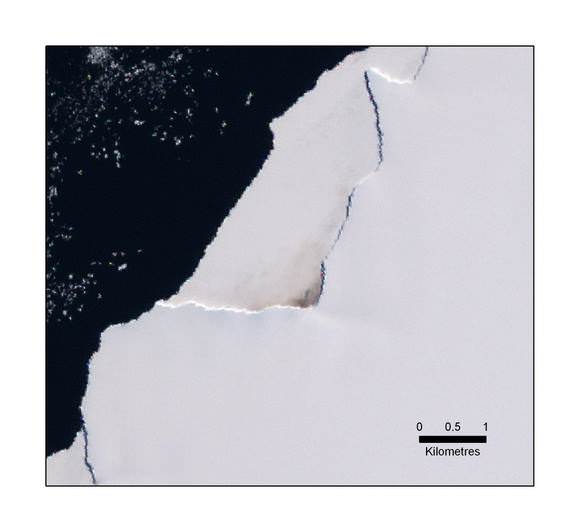

However I think the coolest use of Cherenkov radiation in astronomy is IceCube, which detects the Cherenkov radiation produced by muons in Antarctic ice … traveling upward. These muons are produced by rare interactions of muon neutrinos with hydrogen or oxygen nuclei (in the ice), after they have traveled through the whole Earth, from the Artic (and before that perhaps a few hundred megaparsecs from some distant blazer).

ICAT: imaging Cherenkov Air Telescope

CANGAROO: Collaboration of Australia and Nippon (Japan) for a Gamma Ray Observatory in the Outback

H.E.S.S.: High Energy Stereoscopic System

VERITAS: Very Energetic Imaging Telescope Array System

UHECR: ultra-high-energy cosmic ray

This NASA webpage gives more details of how ICATs work.

Quite a few Universe Today stories are about Cherenkov radiation; for example Astronomers Observe Bizarre Blazar with Battery of Telescopes, and High Energy Gamma Rays Go Slower Than the Speed of Light?.

Examples of Astronomy Casts which include this topic: Cosmic Rays, and Gamma Ray Astronomy.

Sources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cherenkov_radiation

http://abyss.uoregon.edu/~js/glossary/cerenkov_radiation.html