An artist’s impression of Giotto’s brief encounter with comet Halley. Image credit: ESA Click to enlarge

This week the European Space Agency celebrated the 20-year anniversary of the Giotto spacecraft’s encounter with Comet Halley. This was ESA’s first deep space mission, which launched on board an Ariane 1 rocket. Giotto flew for 8 months, traveling almost 150 million kilometres. It swept past the comet on March 13, 1986, getting as close as 596 km (370 miles), and delivered the best pictures ever seen of a comet’s nucleus.

Twenty years ago, in the night between 13 and 14 March 1986, ESA’s Giotto spacecraft encountered Comet Halley. It was ESA’s first deep space mission, and part of an ambitious international effort to solve the riddles surrounding this mysterious object.

The adventure began when Giotto was launched by an Ariane 1 rocket (flight V14) on 2 July 1985. After three revolutions around the Earth, the on-board motor was fired to inject it into an interplanetary orbit.

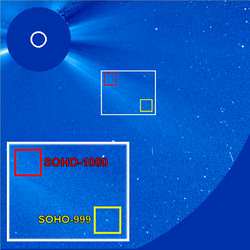

After a cruise of eight months and almost 150 million kilometres, the spacecraft’s instruments first detected hydrogen ions from Halley at a distance of 7.8 million kilometres from the comet on 12 March 1986.

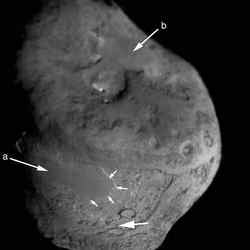

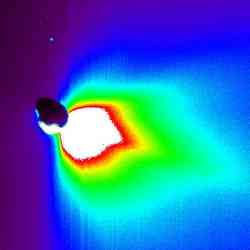

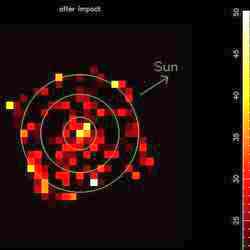

Giotto encountered Comet Halley about one day later, when it crossed the bow shock of the solar wind (the region where a shock wave is created as the supersonic solar particles slow to subsonic speed). When Giotto entered the densest part of the dusty coma, the camera began tracking the brightest object (the nucleus) in its field of view.

Excitement rose at the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, as the first fuzzy images and data came in. The ten experiment teams scrutinised the latest information and struggled to come up with a preliminary analysis.

The first of 12 000 dust impacts was recorded 122 minutes before closest approach. Images were transmitted as Giotto closed in to within a distance of approximately 2000 kilometres, as the rate of dust impacts rose sharply and the spacecraft passed through a jet of material that streamed away from the nucleus.

The spacecraft was travelling at a speed of 68 kilometres per second relative to the comet. At 7.6 seconds before closest approach, the spacecraft was sent spinning by an impact from a ‘large’ (one gram) particle. Monitor screens went blank as contact with Earth was temporarily lost.

TV audiences and anxious Giotto team members feared the worst but, to everyone’s amazement, occasional bursts of information began to come through. Giotto was still alive.

Over the next 32 minutes, the sturdy spacecraft’s thrusters stabilised its motion and contact was fully restored. By then, Giotto had passed within 596 kilometres of the nucleus and was heading back into interplanetary space.

The remarkably resilient little spacecraft continued to return scientific data for another 24 hours on the outward journey. The last dust impact was detected 49 minutes after closest approach. The historic encounter ended 15 March when Giotto’s experiments were turned off.

Original Source: ESA Portal