[/caption]

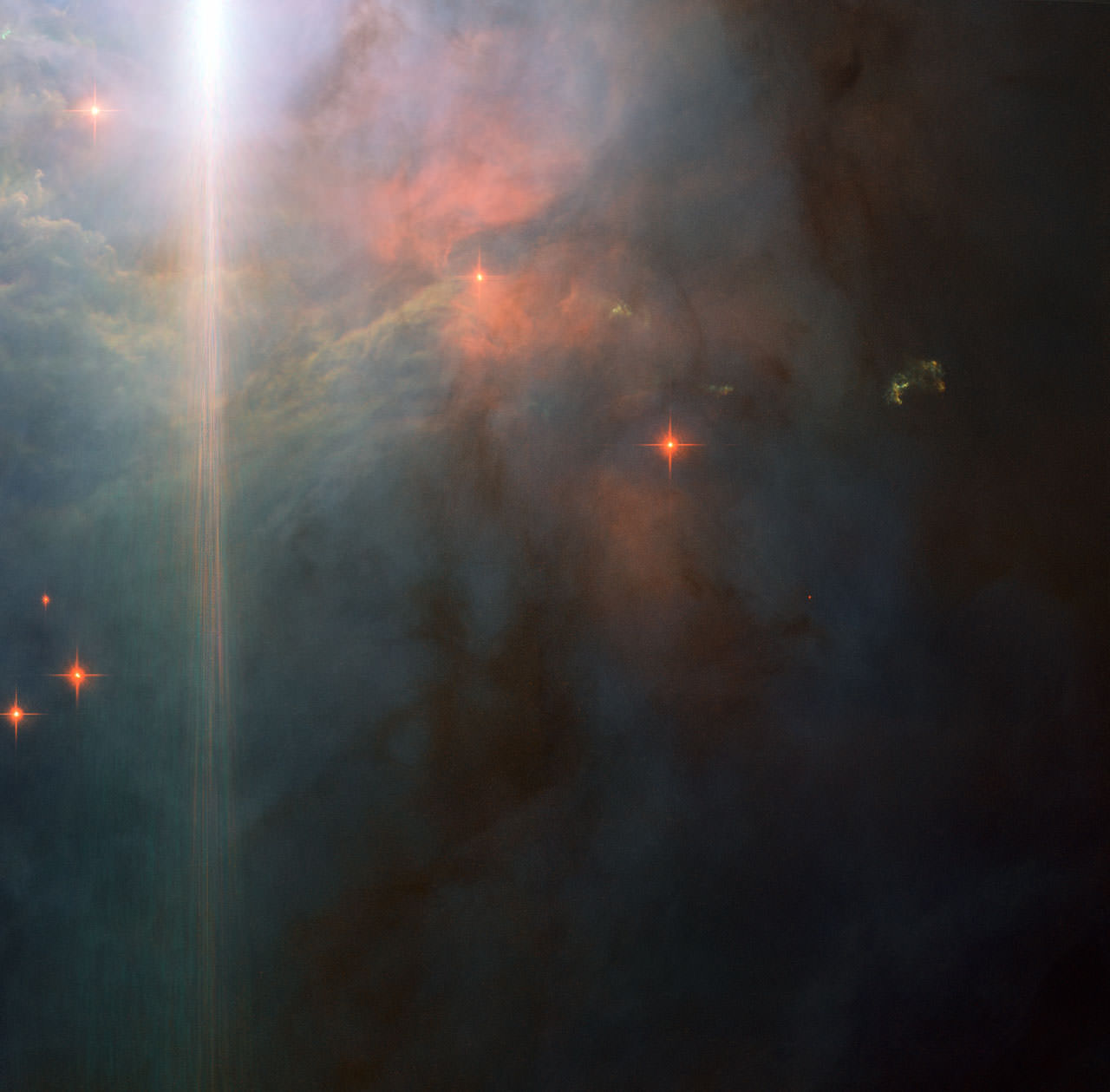

With the annual Perseid Meteor Shower already underway, we’re looking to the skies and thinking about what causes these celestial fireworks. We know for the most part that meteor showers are the by-product of comets, but what happens when seemingly random meteors become not so random? The answer is a long term comet which could be pointed right at Earth.

Comets don’t just wander through the Solar System. They take very specific paths around the Sun and when its orbit passes close to ours, we get visual clues in the form of a meteor shower. Long term comets are in no hurry. Their elliptical sojourns can take anywhere from 200 to 10,000 years to complete – with a dense dust trail leading the way. We compute when and where the comet comes from by its orbital period, but what happens if that orbital period leads to a new discovery? And what happens if that comet’s orbit seems destined to encounter us? We just might get some advance warning from monitoring an unexpected meteor shower.

“Such meteor showers are extremely rare. They happen only about once or twice every sixty years, when the thin meteoroid stream is exactly in Earth’s path at the time when Earth arrives at that spot.” says Peter Jenniskens (SETI Institute) and Peter S. Gural (SAIC). “Because they are so rare, many of these showers remain to be discovered. Here, we report that one such shower, previously unknown, just showed up on February 4, 2011.”

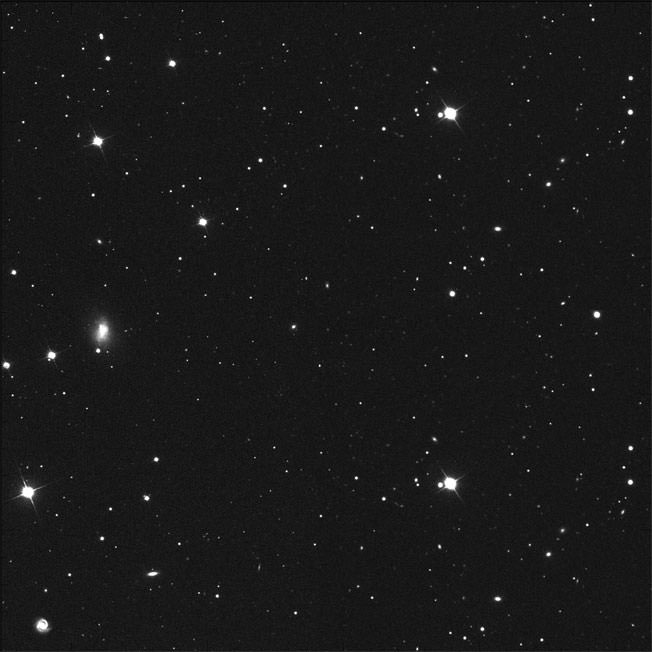

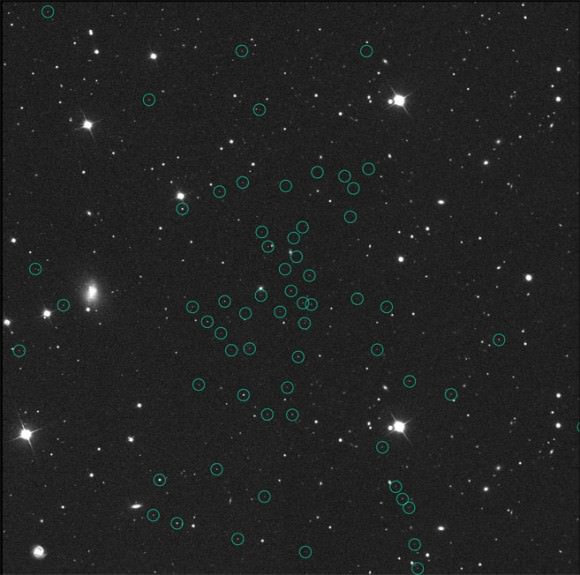

Thanks to the use of the new NASA-sponsored network of low-light video cameras called the Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance (CAMS) project, more than three hundred “new” meteor showers documented by the IAU Working List of Meteor Showers are under investigation. The February 4 occurrence centered around Eta Draconis came as a surprise, but the observing team of three separate stations went to work confirming the meteoroid orbital elements. The event lasted around seven hours and was confirmed through astrometric tracks for all moving objects in all cameras that recorded that night and with radio reflections during that day taken in Finland.

“The similarity of the orbits implies that the February eta Draconids are a dynamically young stream. The orbital period suggests a long-period comet, perhaps a Halley-type comet. If this indeed is a long-period comet dust trail, then the dust was ejected in the previous return to the Sun.” says Jenniskens and Gural. “Such dust trails get perturbed enough on the way in that the orbital periods change dramatically and dust trail sections catch up on each other, spreading out into a more diffuse stream already after one orbit.”

Oddly enough, no meteoritic activity from this new stream was recorded either before or after its February 4th apparition… nor was it active between 2007 through 2009. The conclusion is that it’s caused by the dust trail of a long period comet and it has formally been named the February Eta Draconids. What long term comet does the stream belong to? Well, the answer to that question is still up in the air and a good point to ponder while viewing this year’s Perseids.

“This is an important discovery, because it points to the presence of a potentially hazardous comet. If the dust trail can hit the Earth, so can the comet: the planetary perturbations do not depend on the mass of the object.” says the team. “Of course, an impact will occur only if the comet orbit is perturbed into Earth’s path right at the time when Earth passes by the comet orbit on February 4. It is in principle possible to guard against such impacts by looking along the comet orbit to those spots where the comet would be in such a dangerous position. In that way, perhaps a few years of warning could be provided.”

Original New Story: Space.Com.