The Milky Way measures 100 to 120 thousand light-years across, a distance that defies imagination. But clusters of galaxies, which comprise hundreds to thousands of galaxies swarming under a collective gravitational pull, can span tens of millions of light-years.

These massive clusters are a complex interplay between colliding galaxies and dark matter. They seem impossible to map precisely. But now an international team of astronomers using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope has done exactly this — precisely mapping a galaxy cluster, dubbed MCS J0416.1–2403, 4.5 billion light-years away.

“Although we’ve known how to map the mass of a cluster using strong lensing for more than twenty years, it’s taken a long time to get telescopes that can make sufficiently deep and sharp observations, and for our models to become sophisticated enough for us to map, in such unprecedented detail, a system as complicated as MCS J0416.1–2403,” said coauthor Jean-Paul Kneib in a press release.

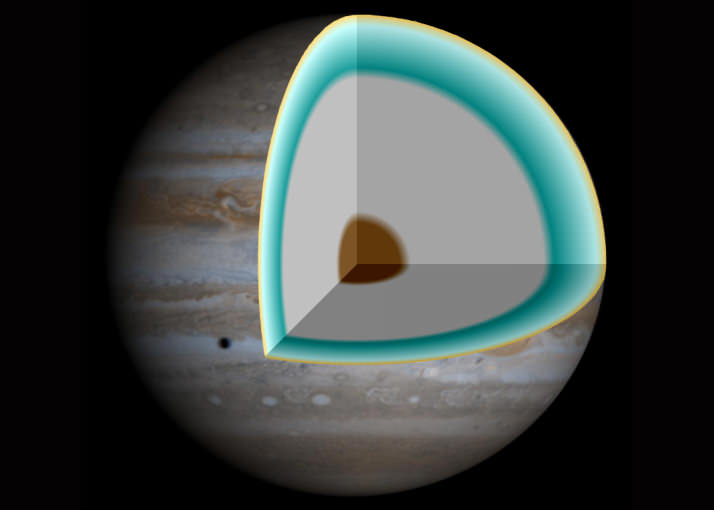

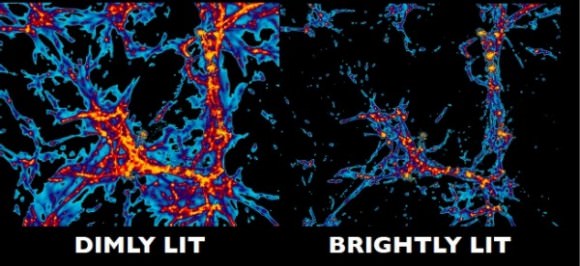

Measuring the amount and distribution of mass within distant objects can be extremely difficult. Especially when three quarters of all matter in the Universe is dark matter, which cannot be seen directly as it does not emit or reflect any light. It interacts only by gravity.

But luckily large clumps of matter warp and distort the fabric of space-time around them. Acting like lenses, they appear to magnify and bend light that travels past them from more distant objects.

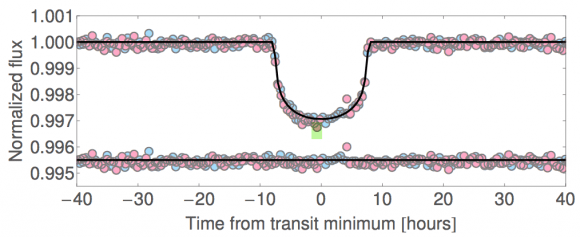

This effect, known as gravitational lensing, is only visible in rare cases and can only be spotted by the largest telescopes. Even galaxy clusters, despite their massive size, produce minimal gravitational effects on their surroundings. For the most part they cause weak lensing, making even more distant sources appear as only slightly more elliptical across the sky.

However, when the alignment of the cluster and distant object is just right, the effects can be substantial. The background galaxies can be both brightened and transformed into rings and arcs of light, appearing several times in the same image. It is this effect, known as strong lensing, which helped astronomers map the mass distribution in MCS J0416.1–2403.

“The depth of the data lets us see very faint objects and has allowed us to identify more strongly lensed galaxies than ever before,” said lead author Dr Jauzac. “Even though strong lensing magnifies the background galaxies they are still very far away and very faint. The depth of these data means that we can identify incredibly distant background galaxies. We now know of more than four times as many strongly lensed galaxies in the cluster than we did before.”

Using Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys, the astronomers identified 51 new multiply imaged galaxies around the cluster, quadrupling the number found in previous surveys. This effect has allowed Jauzac and her colleagues to calculate the distribution of visible and dark matter in the cluster and produce a highly constrained map of its mass.

The total mass within the cluster is 160 trillion times the mass of the Sun, with an uncertainty of 0.5%. It’s the most precise map ever produced.

But Jauzac and colleagues don’t plan on stopping here. An even more accurate picture of the galaxy cluster will have to include measurements from weak lensing as well. So the team will continue to study the cluster using ultra-deep Hubble imaging.

They will also use ground-based observatories to measure any shifts in galaxies’ spectra and therefore note the velocities of the contents of the cluster. Combining all measurements will not only further enhance the detail, but also provide a 3D model of the galaxies within the cluster, shedding light on its history and evolution.

This work has been accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomy and is available online.