Venus is known as Earth’s Sister Planet. It’s roughly the same size and mass as Earth, it’s our closest planetary neighbor, and Venus and Earth grew up together.

When you grow up with something, and it’s always been there, you kind of take it for granted. As a species, we occasionally glance over at Venus and go “Huh. Look at Venus.” Mars, exotic exoplanets in distant solar systems, and the strange gas giants and their moons in our own Solar System attract much more of our attention.

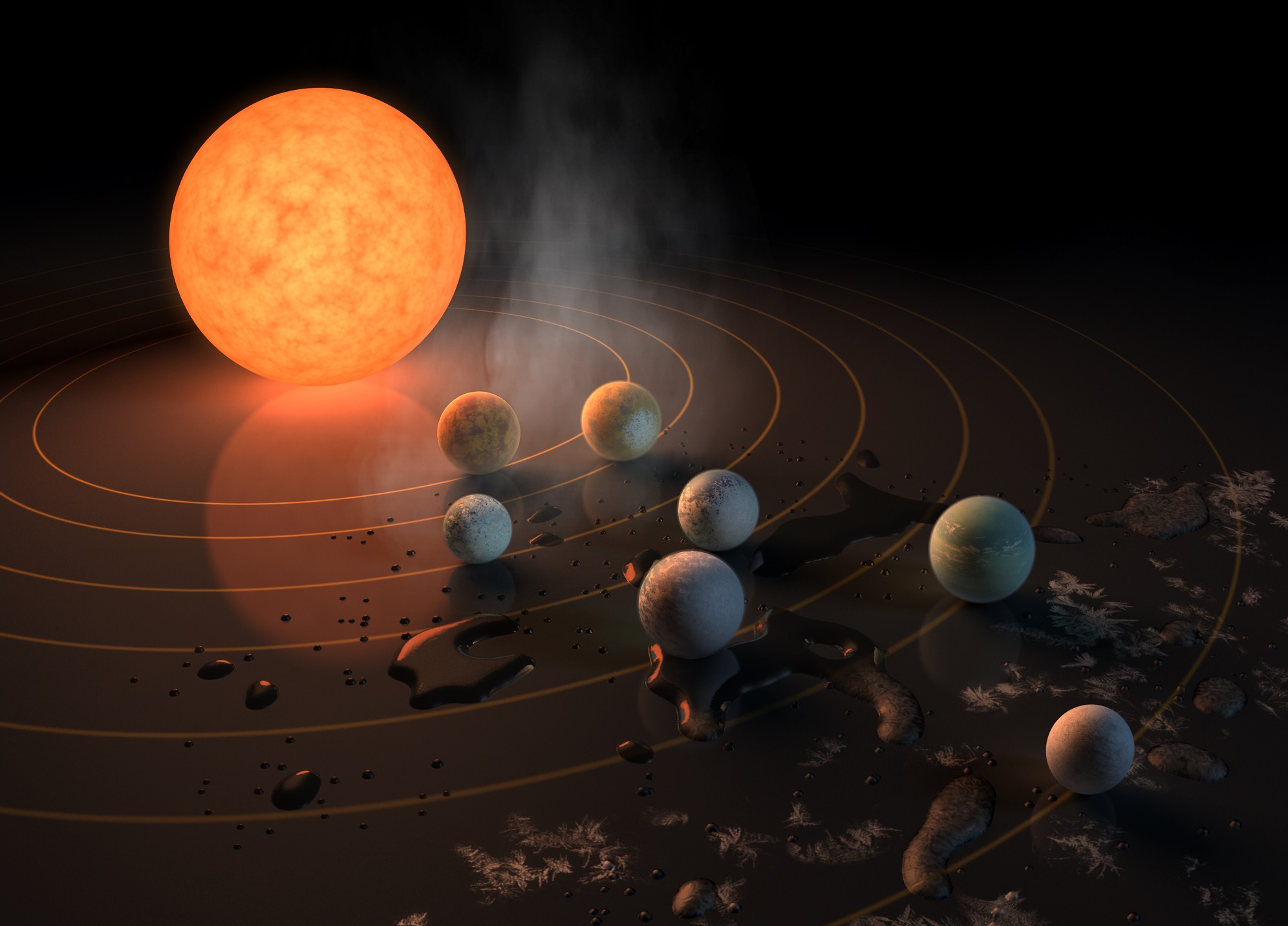

If a distant civilization searched our Solar System for potentially habitable planets, using the same criteria we do, then Venus would be front page news for them. It’s on the edge of the habitable zone and it has an atmosphere. But we know better. Venus is a hellish world, hot enough to melt lead, with crushing atmospheric pressure and acid rain falling from the sky. Even so, Venus still holds secrets we need to reveal.

Chief among those secrets is, “Why did Venus develop so differently?

Conditions on Venus pose unique challenges. The history of Venus exploration is littered with melted Soviet Venera Landers. Orbital probes like Pioneer 12 and Magellan have had more success recently, but Venus’ dense atmosphere still limits their effectiveness. Advances in materials, and especially in electronic circuitry that can withstand Venus’ heat, have buoyed our hopes of exploring the surface of Venus in greater detail.

At the Planetary Science Vision 2050 Workshop 2017, put on by the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI) a team from the Southwest Research Institute (SWRI) examined the future of Venus exploration. The team was led by James Cutts from JPL.

The group acknowledged several over-arching questions we have about Venus:

- How can we understand the atmospheric formation, evolution, and climate history?

- How can we determine the evolution of the surface and interior?

- How can we understand the nature of interior-surface-atmosphere interactions over time, including whether liquid water was ever present?

Since the Vision 2050 Workshop is all about the next 50 years, Cutts and his team looked at the challenges posed by Venus’ unique conditions, and how they could answer questions in the near-term, mid-term, and long-term.

Near Term Exploration (Present to 2019)

Near-Term goals for the exploration of Venus include improved remote-sensing from orbital probes. This will tell us more about the gravity and topography of Venus. Improved radar imaging and infrared imaging will fill in more blanks. The team also promoted the idea of a sustained aerial platform, a deep probe, and a short duration lander. Multiple probes/dropsondes are also part of the plan.

Dropsondes are small devices that are released into the atmosphere to measure winds, temperature, and humidity. They’re used on Earth to understand the weather, and extreme phenomena like hurricanes, and can fulfill the same purpose at Venus.

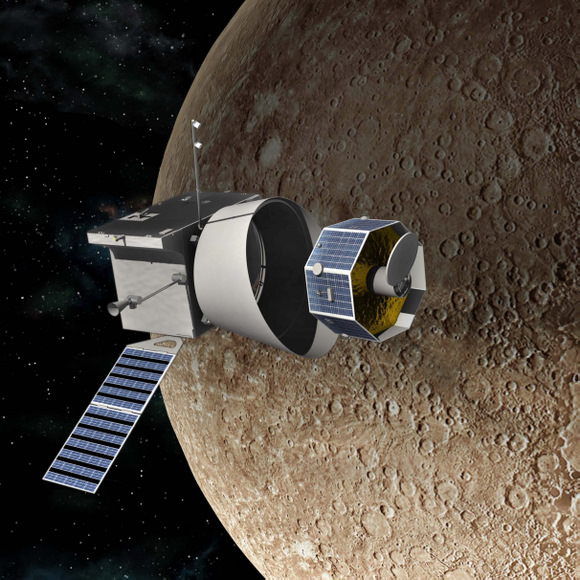

In the near-term, missions whose final destination is not Venus can also answer questions. Fly-bys by craft such as Bepi-Colombo, Solar Probe Plus, and the Solar Orbiter missions can give us good information on their way to Mercury and the Sun respectively. These missions will launch in 2018.

The ESO’s Venus Express and Japan’s Akatsuki, (Venus Climate Orbiter), have studied Venus’ climate in detail, especially its chemistry and the interactions between the atmosphere and the surface. Venus Express ended in 2015, while Akatsuki is still there.

Mid-Term Exploration (2020-2024)

The mid-term goals are more ambitious. They include a long-term lander to study Venus’ geophysical properties, a short-duration tessera lander, and two balloons.

The tesserae lander would land in a type of terrain found on Venus known as tesserae. We think that at one time, Venus had liquid water on it. The fundamental evidence for this may lie in the tesserae regions, but the terrain is extremely rough. A short duration lander that could land and operate in the tesserae regions would help us answer Venus’ liquid water question.

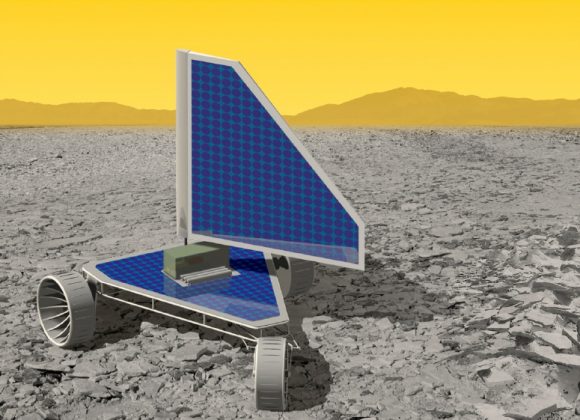

Thanks to the continued development of heat-hardy electronics, a long-term duration lander (months or more) is becoming more feasible in the mid-term. Ideally, any long-term mobile lander would be able to travel tens to hundreds of kilometers, in order to acquire a regional sample of Venus’ surface. This is the only way to take geochemistry and mineralogy measurements at multiple sites.

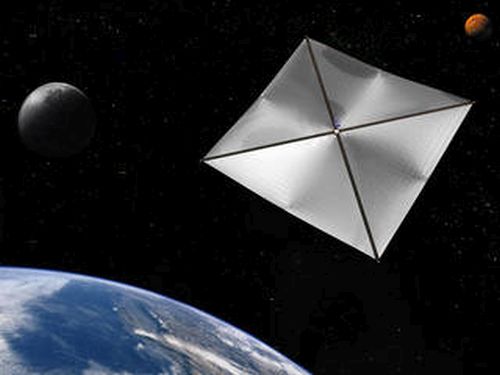

On Mars the landers are solar-powered. Venus’ thick atmosphere makes that impossible. But the same dense atmosphere that prohibits solar power might offer another solution: a sail-powered rover. Old-fashioned sail power might hold the key to moving around on the surface of Venus. Because the atmosphere is so dense, only a small sail would be necessary.

Long-Term Exploration (2025 and Beyond)

The long-term goals from Cutts and his team are where things get really interesting. A long-lived surface rover is still on the list, or possibly a near-surface craft like a balloon. Also on there is a long-lived seismic network.

A seismic network would really start to reveal the secrets behind Venus’ geophysical life. Whereas a lander would give us estimates of seismic activity, they would be crude compared to what a network of seismic sensors would reveal about Venus’ inner workings. A more thorough understanding of quake mechanisms and locations would really get the theorists buzzing. But it’s the final thing on the list that would be the end-goal. A sample-return mission.

We’re getting good at in situ measurements on other worlds. But for Venus, and for all the other worlds we have visited or want to visit, a sample return is the holy grail. The Apollo missions brought back hundreds of kilograms of lunar samples. Other sample-return missions have been sent to Phobos, which failed, and to asteroids, with varying degrees of success.

Subjecting a sample to the kind of deep analysis that can only be done on labs here on Earth is the end-game. We can keep analyzing samples as we develop new technologies to examine them with. Science is iterative, after all.

The 2003 Planetary Science Decadal Survey identified the importance of a sample return mission to Venus’ atmosphere. A balloon would float aloft in the clouds, and an ascending rocket would launch a collected sample back to Earth. According to Cutts and his team, this kind of sample-return mission could act as a stepping stone to a surface sample mission.

A surface sample would likely be the pinnacle of achievement when it comes to understanding Venus. But like most of the proposed goals for Venus, we’ll have to wait awhile.

The Changing Future

Cutts and the team acknowledge that the technology to enable exploration of Venus is in flux. No more missions to Venus are planned before 2020. There’ve been proposals for things like sail powered landers, but we’re not there yet. We’re developing heat-resistant electronics, but so far they’re very simple. There’s a lot of work to do.

On the other hand, some things may happen sooner. It may turn out that we can learn about Venusian seismic activity from balloon-borne or orbital sensors. The team says that “Due to strong mechanical coupling between the atmosphere and ground, seismic waves are launched into the atmosphere, where they may be detected by infrasound on a balloon or infrared or ultraviolet signatures from orbit.” That’s thanks to Venus’ dense atmosphere. That means that the far-term goal of seismic sensing of the interior of Venus could be shifted to the near-term or mid-term.

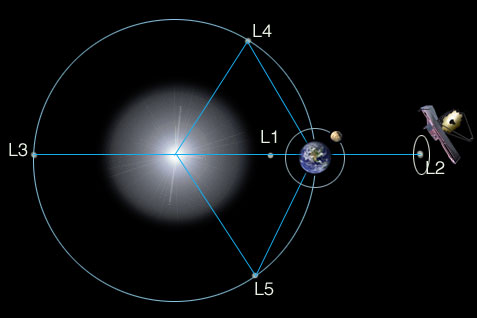

As work on nanosatellites and cubesats continues, they may play a larger role at Venus, and shift the timelines. NASA wants to include these small satellites on every launch where there is a few kilograms of excess capacity. A group of these nanosatellites could form a network of seismic sensors much more easily and much sooner than an established network of surface sensors. A network of nanosatellites could also serve as a communications relay for other missions.

Venus doesn’t generate a lot of buzz these days. The discovery of Earth-like worlds in distant solar systems generates headline after headline. And the always popular search for life is centered on Mars, and the icy/sub-surface moons of our Solar System’s gas giants. But Venus is still a tantalizing target, and understanding Venus’ evolution will help us understand what we’re seeing in distant solar systems.